Have you seen Canada’s new passport? Each page is designed as a snapshot of Canadian history, a representation of people and places that have formed our nation. We see pictures of Confederation, the Bluenose, the Last Spike – many images of exploration and development. Surprisingly, we do not see pictures of Canada as many of us imagine it: a vast landscape of untouched nature, a country of loons, beavers, boreal forests and polar bears.

Have you seen Canada’s new passport? Each page is designed as a snapshot of Canadian history, a representation of people and places that have formed our nation. We see pictures of Confederation, the Bluenose, the Last Spike – many images of exploration and development. Surprisingly, we do not see pictures of Canada as many of us imagine it: a vast landscape of untouched nature, a country of loons, beavers, boreal forests and polar bears.

The new passport does, however, include oil wells as one of its “iconic” Canadian images. This is no mistake: Canada is the sixth-largest crude oil producer in the world, and according to the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers it holds the planet’s third largest reserves after Venezuela and Saudi Arabia.

But while Canada expands its petro-industry, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has provided unequivocal proof that the climate is changing. IPCC reports show that changes will likely trigger extreme weather events, such as heat spells, floods and storms, all with potentially devastating impacts. Let us remember the cost, distress and damage caused by the 2013 Calgary flood and Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

Carbon dioxide is a principal greenhouse gas. To minimize the negative consequences of a changing climate, it is therefore necessary to “decarbonize” our economies. To do so, we must move away from fossil fuels as a main source of energy. The United Kingdom has led the move to decarbonize through the adoption of their Climate Change Act (2008), which targets greenhouse gas emission levels at least 80 per cent lower than 1990 by the year 2050.

But can Canada begin to decarbonize while also maintaining – or increasing – fossil fuel production? Is Canada investing in an energy source that is growing obsolete, or at least too environmentally costly to rely on? Is it possible to continue extracting oil while remaining committed to environmental protection? These questions are fundamental to Canada’s future.

According to several economists, including Nobel prize-winner Joseph Stiglitz, limited economic indicators such as the gross domestic product are not an adequate measure of sustainability or of “social progress.” The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) therefore developed green growth indicators to capture the complex reality of sustainability. Beyond measuring economic growth, OECD indicators aim to:

- measure environmental and resource productivity, such as CO2 productivity, energy productivity and material productivity;

- monitor the natural asset base of the economy such as freshwater, land and wildlife resources; and

- monitor economic opportunity and policy responses, such as green technology and innovation, environmental pricing, taxes and transfers.

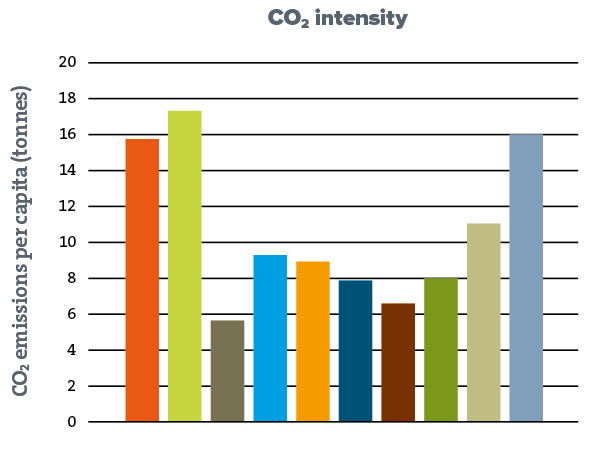

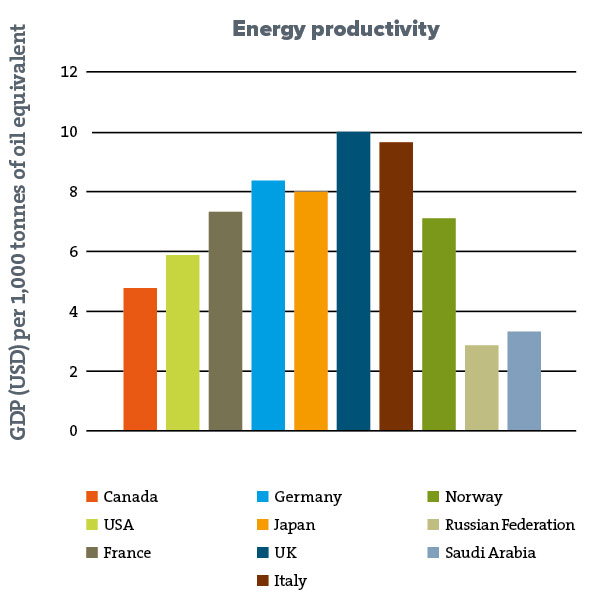

The OECD indicators suggest that Canada is currently running a sustainability deficit. Citizens of Canada and the US produce the highest amount of carbon dioxide per capita of all G8 countries. Canada also sports the lowest levels of energy efficiency of G8 countries (excluding Russia), as measured by the energy requirements for economic growth, although its energy efficiency is higher than that of Russia and Saudi Arabia.

How can Canada make up for this sustainability deficit?

In this dedicated special issue of A\J, an interdisciplinary team of scholars concerned with climate change and sustainability propose a range of solutions. The ideas developed in the following pages are part of a concerted effort by more than 60 researchers from across the country who have joined an initiative called the Sustainable Canada Dialogues. Eyeing the 2015 federal election, Sustainable Canada Dialogues is an effort to engage with Canadian voters and policy makers to bring the know-how developed in our universities into broader society. Through the mobilization of scholarly expertise, the initiative proposes science-based and viable actions and policy options that could help Canada in the necessary transition to more sustainable development.

At the heart of sustainability is the idea that present lifestyles should not privilege current generations at the expense of those to come. Sustainability entails taking the future needs of our grandchildren – and their children – into account as we use our natural resources. Sustainability thus makes a key distinction between renewable resources, such as wind and sun, and non-renewable ones, such as oil and minerals.

Economist Geoffrey Heal has suggested that the wealth derived from the extraction of non-renewable resources be invested in the development of what he calls intellectual and physical capital. Essentially, he proposes that if the income from non-renewable resource extraction is invested in education, infrastructure and technological innovation, future generations will inherit opportunities despite the ongoing depletion of some natural assets.

Heal presents Norway, a petroleum-producing country, as a model of soft sustainable development. Why? First, Norway derives important revenue from the income tax levied on businesses and a special tax on oil extraction, resulting in an overall taxation rate of greater than 75 per cent for petroleum production. The revenues from oil extraction are then deposited in the Government Pension Fund Global, the wealthiest pension fund in the world. Furthermore, accepting its responsibility as a petroleum-producing country, Norway has made a pledge to be carbon neutral by 2050. As part of this commitment to carbon neutrality, the Government of Norway developed an International Climate and Forest Initiative. This initiative has supported activities to reduce tropical deforestation in 10 tropical countries with an investment of more than $US1.9-billion since 2008. Finally, Norway is ranked first in the world for its Human Development Index, an indicator developed by the United Nations Development Programme that combines measures of life expectancy, educational attainment and income into a composite ranking. Norway has thus demonstrated that, despite popular belief, sustainability can lead to high living standards.

In 2014, Canada ranked eighth on the Human Development Index, a fairly good performance. More recently, however, the Conference Board of Canada gave the country a “C” for its “mediocre job in ensuring income equality.” This grade raises important considerations: The alleged success of Canada’s economy is clearly not benefiting everyone. If our political elite continue to tie our future to oil extraction, why not emulate the Norwegian model and demand a Canada Sustainability Fund to help pay for efforts toward decarbonizing our economy? Why not join Norway and help combat tropical deforestation? Canada’s petrodollars could contribute to the well-being of current and future generations.

The scholars of the Sustainable Canada Dialogues believe that in order to address our nation’s sustainability deficit, we must adopt bold new policies, practices and definitions of sustainability. The good news is that many Canadians are already thinking along these lines.

Consider Vancouver’s Greenest City 2020 Action Plan. This ambitious plan specifies 10 explicit targets for a green economy, climate leadership, green buildings, green transportation, zero waste, access to nature, a lighter footprint, clean water, clear air and locally sourced foods. Vancouver’s plan hinges on higher-density urban living, which includes the development of urban parks and schools to ensure a high quality of life in Vancouver. Laneway houses that allow families to live close to downtown areas are providing an increasingly fashionable and sustainable antidote to suburban expansion.

In Montreal, sustainability efforts are focused on bicycling, despite the city’s deep winter cold. In 2013, Montreal was ranked the most bicycle-friendly city in North America and eleventh in the world. Since transportation is responsible for one quarter of Canada’s total carbon dioxide emissions, active modes of transportation such as cycling and walking offer significant opportunities to reduce the volume of air pollutants and greenhouse gases. Active transport is also linked to reduced noise and traffic congestion, decreased crime rates, increased levels of physical fitness and lower transportation expenditures. Did you know you could accomplish so much just by riding your bike?

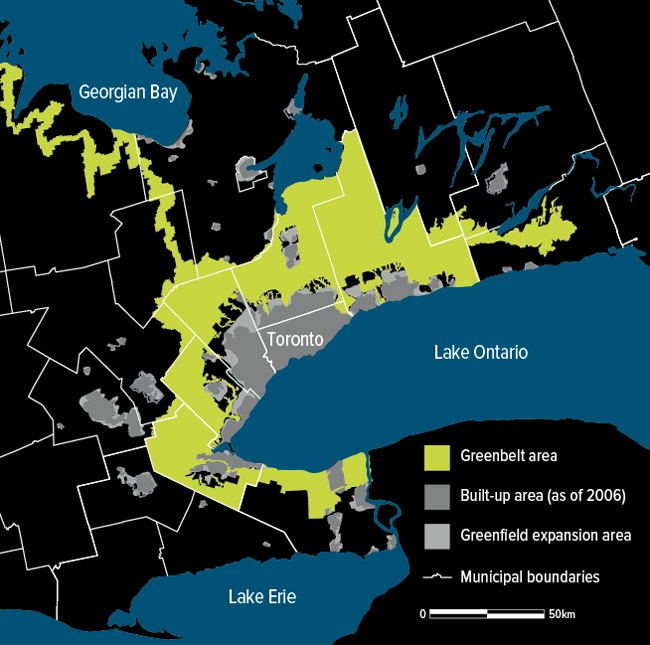

The desire of a growing number of Canadians to eat locally produced organic food is another sustainable habit that should be nourished. The Ontario Greenbelt illustrates a smart approach to the broad-scale transformation needed to shift lifestyles to smaller, more local scales. The Greenbelt’s agricultural lands produce 12 per cent more gross income than the average Ontario farm per hectare, even though greenbelt farms are 33 per cent smaller on average. All that local and organic produce feeds the cultural shift toward a healthier lifestyle – and a locally grown tomato tastes much better!

There are countless other examples of sustainability initiatives in Canada. The challenge is to scale up their numbers and their reach. This will require a broader political will and more radical shifts in policy.

Scholars from Sustainable Canada Dialogues have worked to identify possible action items on climate change and sustainability, many of which are illustrated in this special issue. Our work has also included visioning workshops where participants presented an object, activity or place they cherish and would like to pass onto the next generation but feel may be threatened by environmental change. People told us, for example, that Canadian microbrews taste so good because our water is so clean. They told us stories of canoe trips in pristine waters and drinking directly from Canadian lakes. They recalled the sense of peace found in accessible yet wild landscapes. Some participants shared the pleasures of travelling and discovering new places and their fear that climate change might increase global unrest and rob the next generations of rich cultural exchange. Others emphasized the inextricable link between our food and the well-being of the earth’s pollinators.

Sustainable Canada Dialogues also listened to the dreams Canadians hold for the future. Despite the differences among individuals, we heard many similarities. We heard Canadians ask for locally focused economies, cultural openness and equal opportunity for all. We heard that access to clean air and water and preservation of traditions and natural habitat are very important to the country’s well-being. We were told that Canadians desire a healthy work-life balance supported by both local and national economies. We heard demands for more honest and transparent dialogue regarding the marketing of food, as well as agreement on the need for more sustainable transportation and food production. We heard an insistent call for the redefining of wealth.

These dreams of the future draw us back to the importance of dialogue, of engaging in the vision of our country. The imagery in our new passport is meant to capture Canada’s yesterday. But tomorrow is born out of the actions we take today. We have the responsibility and ability to design this future.

Natalie Richards is an MSc candidate in the Department of Biology at McGill University.

Catherine Potvin is a plant ecologist and professor in the Department of Biology at McGill University who has worked on issues relating to climate change and sustainability since the early 1980s.