What greenbelts do

Ontario’s Greenbelt

What greenbelts do

Ontario’s Greenbelt

THE GREENBELT PLAN is a key component of the province’s growth management strategy for the Greater Golden Horseshoe, defining where development is off-limits. It takes a systems-based approach to planning, protecting more than individual natural features by incorporating the areas that surround, connect and support them. The Plan ensures that linkages between significant landforms – such as the Niagara Escarpment, Oak Ridges Moraine and the surrounding major watersheds and lakes – are protected, and includes speciality crop areas in Niagara and the Holland Marsh.

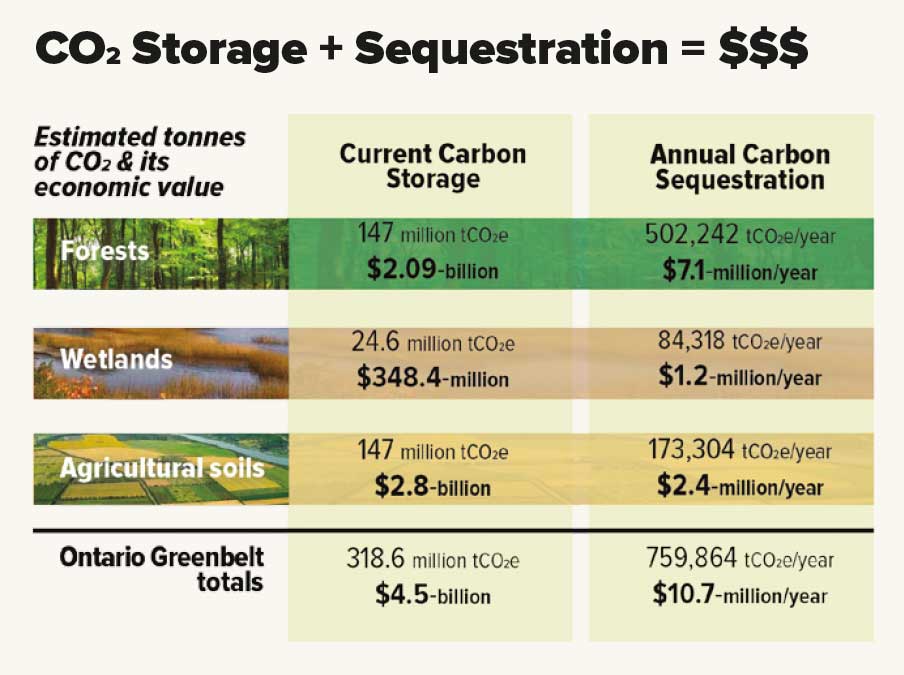

The Greenbelt makes significant contributions to the provincial economy. A 2012 study found that the total economic impact of the Greenbelt exceeds $9.1-billion annually, drawing revenue from the tourism, recreation, forestry and agricultural sectors. An additional $2.6-billion in benefits is provided annually by rich soil, forests and wetlands that filter our air, clean our water and protect us from floods.

The 10-year review of the Greenbelt Plan will take stock and identify ways to improve strategy, implementation and related policies. In light of changing global conditions such as climate change, water scarcity and food insecurity, the review will need to consider future challenges to ensure that the Greenbelt continues to help communities grow sustainably.

– Kathy Macpherson, vice president of research and policy, Friends of the Greenbelt Foundation

Green Wedges, Melbourne, Australia

MELBOURNE HAS A 40-YEAR-OLD strategic plan to confine fringe metropolitan growth to linear corridors separated by “green wedges.” This plan showed that a city-wide strategy to incorporate urban hinterlands is essential to preventing the indiscriminate development of greenbelts by fragmented and competing local authorities.

The city’s strategic plan was updated in 2002 to expand the green wedges into a true greenbelt, spanning 17 local councils. Local government introduced stronger rural zones and legislative protection for an urban growth boundary (UGB). This plan sought to divert up to 40 per cent of outer urban growth to the metropolitan area, reducing pressure on the wedges. Instead, a politicized planning process and the development industry’s power have since freed up 60,000 hectares by moving the UGB.

The best protection for greenbelts is an inflexible UGB separating urban and rural uses, along with a metropolitan-wide, regional identification of land supply and urban densities. The future of Melbourne’s wedges is now threatened (and the impact of the UGB is undermined) by the proposed introduction of hotels, restaurants, resorts and other industry.

Melbourne’s greenbelt provides many vital functions that make the city more resilient in a time of rapid change. Wedges are the second largest food-producers in the state of Victoria, and they provide crucial environmental services, including much of Melbourne’s water supplies, and important flora and fauna reserves. These services have a wide range of important economic values.

– Michael Buxton, professor of Environment and Planning, School of Global, Urban and Social Studies, RMIT University, Australia

São Paulo City Green Belt Biosphere Reserve, Brazil

SÃO PAULO links the major economic regions of Latin America into the world economy. Yet the city has long faced centrifugal urbanization, characterized by spatial segregation, pollution and poverty. For most of the 20th century, environmental degradation and an advancing city frontier had severe impacts on the ecosystem services that it depends on. After citizens opposed the Metropolitan Perimetral Road Project in 1989, UNESCO designated the city’s periphery as the São Paulo City Green Belt Biosphere Reserve. In 1993, it became part of the Mata Atlantica Biosphere Reserve.

Biosphere reserves are tools for integrated land management that aim to conserve biodiversity, stimulate economic activity and offer logistical support for sustainable development. São Paulo’s was designed to embrace the metropolis and advance towards its centre. With challenges like fires, real estate speculation, infrastructure work and industrial sprawl, this protected natural belt joins large stretches of native forests, watersheds and coastal areas, agricultural lands and urban systems. It stabilizes ecosystem services, including the water supply, hillside and soil integrity, as well as the climate against the advancement of heat islands. Above all, it sustains São Paulo’s global economic role by providing a framework for managing the city and its conservation areas.

– Karl-Heinz Gaudry Sada, research associate, Institute for Geo- and Environmental Sciences, and Institute for Socio-Environmental Sciences and Geography, University of Freiburg, Germany

Challenges to Ontario’s Greenbelt

Policy can fail some communities

THE ESTABLISHMENT of Ontario’s Greenbelt in 2005 – along with revisions to the Planning Act and Provincial Policy Statement, the Places to Grow legislation, and the plan and creation of Metrolinx – represented the most significant engagement in regional planning for the Greater Golden Horseshoe that the province has ever witnessed. However, the impact of these interventions on the sustainability of urban and rural communities in the region remains an open question.

The Greenbelt protected a substantial swath of rural lands from urbanization and established critical connections between the Niagara Escarpment and Oak Ridges Moraine. At the same time, it permitted the large body of rural land already scheduled for development by municipalities to stand untouched. It left additional tracts, sufficient to support low-density urban development for decades, between its inner boundaries and the existing limits of planned development. Perhaps even more seriously, the Greenbelt’s limited northern boundaries left open the possibility of leapfrog development on its outer fringe.

That scenario now seems to be playing out about an hour’s drive north of Toronto, particularly in southern Simcoe County, aided and abetted by the province’s recent Simcoe Sub-Area Amendment to the Places to Grow Act. The result, like so much of the McGuinty government’s environmental legacy, is a mixture of some dramatic steps forward, but also countervailing reaffirmations of commitments to relatively conventional (and unsustainable) development paths.

– Mark S. Winfield, associate professor of Environmental Studies & chair of the Sustainable Energy Initiative, York University

Leapfrogging

THE PROBLEM of leapfrog development occurs when new subdivisions are built beyond the protected Greenbelt, chewing up farmland and forests with more sprawl, rather than in areas that are already urbanized, as intended.

Simcoe County is a prime example: the suburbs are going to explode around small towns, where there are few jobs, and where commute times to York Region and Toronto are long. New developments are mostly low density, making it less likely that people will have access to efficient public transit and more likely that they’ll drive into work each day, creating pressure for more highways through the Greenbelt.

While there’s no silver bullet, a good first step would be to make developers pay the full cost of their projects. Right now, taxpayers pay for the infrastructure to support sprawling, inefficient housing, such as water, sewer pipes and electricity. This makes it cheaper for developers to build low-density subdivisions by paving over farmland, rather than creating high-density housing in existing urban centres. We need to reverse this; developers should be rewarded for building liveable communities that use less energy and water, or pay the cost of their sprawl.

The Ontario government also needs to get serious about holding municipalities to account for delivering on the goals of the Places to Grow Act by protecting natural heritage and directing higher density development into existing towns and cities.

– Gillian McEachern, campaigns director, Environmental Defence

Landbanking

LANDBANKING involves the strategic purchase of huge tracts of land for future development. Landbankers such as Walton International have been paying much higher than market value for parcels of farmland around the Ontario and Ottawa greenbelts, then reselling ownership to mainly offshore investors. (Walton and its subsidiaries alone own about 5,260 hectares just outside the province’s greenbelts.) Landbankers typically gain enough influence over municipalities to rezone foodland for sprawl development, and to lobby provincial and municipal governments to build roads, sewers and water pipelines. The rezoned land becomes much more valuable and is resold at inflated prices, with the profits going to the offshore investors.

The land buying process is often highly secretive. Heritage farms that have been cultivated for generations are sold off, dividing farming communities and often destroying relationships between neighbours and within farm families. While some farmers become instant millionaires, the landbankers’ strategy drives up adjacent land value and taxes, making it unaffordable for other farmers. Once heritage farmsteads are purchased, they are neglected by the landbankers and can become dilapidated “agrislums” that are eventually bulldozed, and those farming communities lose their critical mass. While many remaining residents become resigned, others work to stop the sprawl, including groups such as Sustainable Brant, Preserving Agricultural Lands Society and Tutela Heights Phelps Road Residents Association.

How can we fix this problem? The first steps should be to protect all Ontario farmland with legislation similar to what the Greenbelt has, and lobby the provincial government to reinstate property taxes for non-residents.

– Ella Haley, farmer, activist and assistant professor of Sociology at Athabasca University

Perceptions and barriers

GREENBELT 2.0 should focus on celebrating and enhancing the Greenbelt as it exists today. Expansion should not be the priority, beyond adding ravine systems or other natural features that already intersect with the Greenbelt. The priority should be to help Greater Golden Horseshoe residents and businesses understand the Greenbelt as much more than a barrier to development. It is a garden, a playground and a home for countless species, as well as a working landscape that is a source of livelihood for farmers, vintners, tour operators and other businesses.

The Greenbelt is vast and varied, but poorly understood. Most people’s interactions do not go beyond reading the road signs marking its boundaries across highways. Future initiatives should strive to make all aspects of the Greenbelt known to those of us who live in and near it. When the many millions of people whose lives are impacted by this swath of land understand that it allows us to have cleaner air and water, local food and access to natural spaces, its protection will not be tied solely to legislation that can change with the seasons.

– Leah Birnbaum, urban planning consultant

Greenbelts are socially and economically relevant – not just a pretty face.

UNDENIABLY, the Ontario Greenbelt is beautiful. It has the craggy cliffs of the escarpment running from Niagara to the Bruce Peninsula, and the lush forest of the Oak Ridges Moraine moving eastwards. But the Greenbelt wasn’t created just to maintain a pristine environment; it also preserves a prime and productive landscape.

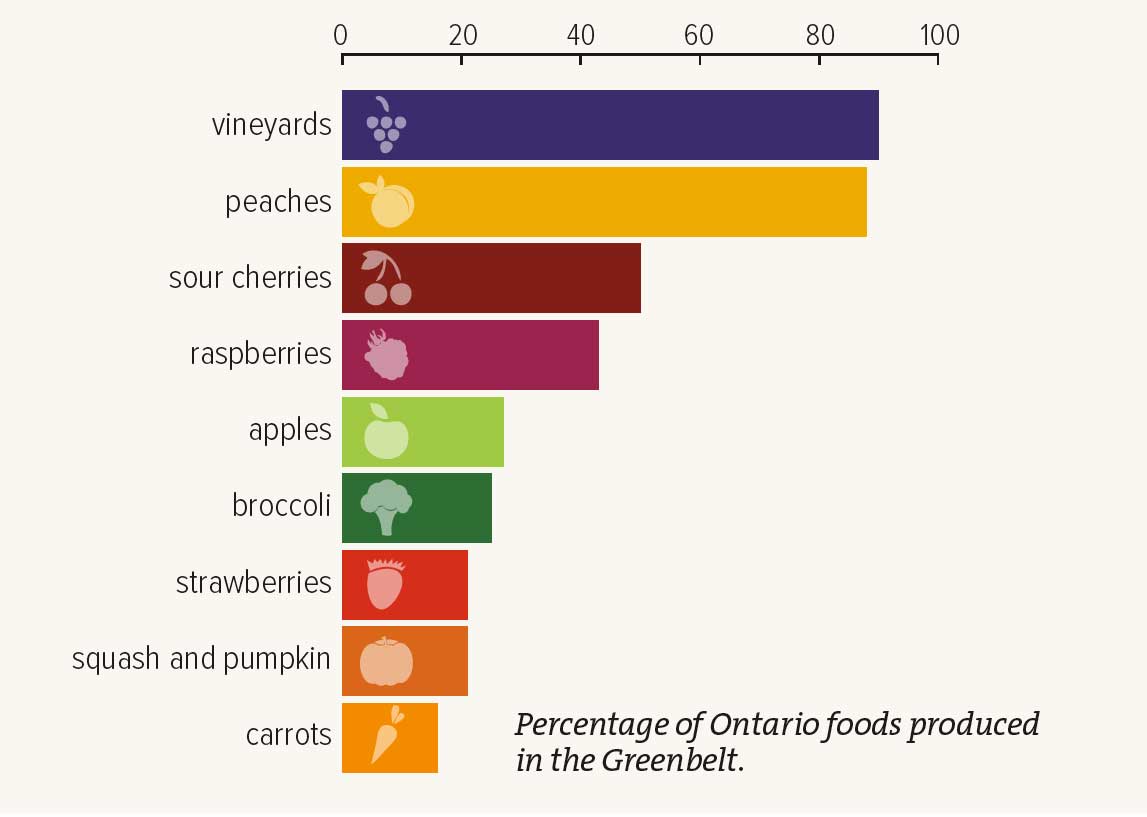

The Greenbelt is an internationally recognized economic powerhouse. Made up of 62 per cent productive agricultural lands and more than 7,000 farms, it is the heart of Ontario’s local food system, and forms a significant part of the second largest farming and food processing cluster in North America. The Greenbelt provides 161,000 direct and indirect jobs for a range of leading industries, including tourism and recreation.

The Greenbelt is also crucial to Ontario’s growing communities. High-quality green spaces play an important role in building competitive cities and regions by increasing their liveability, which goes beyond the purely aesthetic value of being close to nature. Locals actively enjoy the landscape through activities like hiking, biking or snowshoeing. Communities like Ajax and Burlington regularly tout their balance between urban and rural as a selling feature.

Whether it’s fresh air, clean water, healthy local food or all three, what’s clear is that the world’s largest greenbelt is working for both our environment and our economy.

– Burkhard Mausberg, CEO, Friends of the Greenbelt Foundation