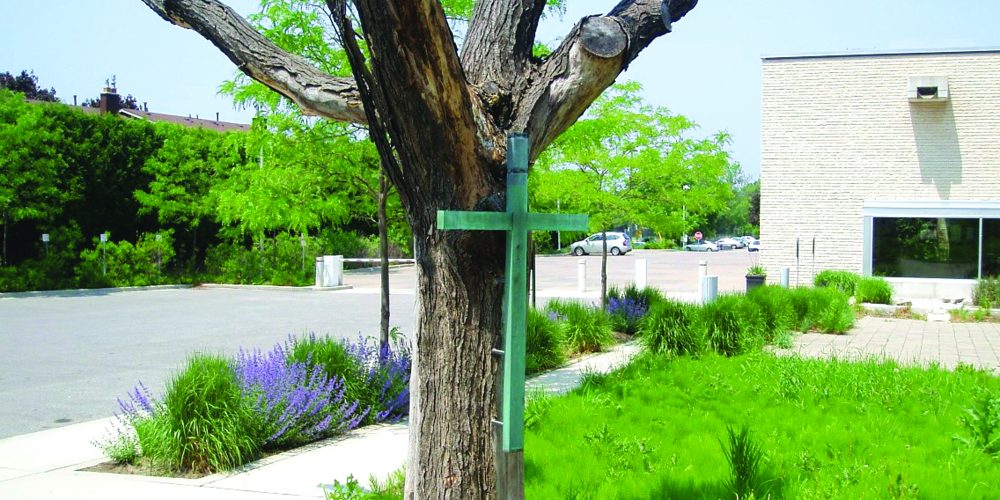

St Gabriel’s Roman Catholic Church in Toronto is the first sacred building in Canada to be LEED Gold (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certified. People from outside its community often come to marvel at its environmentally sustainable architecture, living wall, sophisticated ventilation system, and indigenous plants. In tours with inquisitive visitors, ecotheologian Dennis O’Hara explains, “There are two books of revelation, scripture and creation. All of God’s creation is sacred, and not just the inner sanctuary.”

St Gabriel’s Roman Catholic Church in Toronto is the first sacred building in Canada to be LEED Gold (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certified. People from outside its community often come to marvel at its environmentally sustainable architecture, living wall, sophisticated ventilation system, and indigenous plants. In tours with inquisitive visitors, ecotheologian Dennis O’Hara explains, “There are two books of revelation, scripture and creation. All of God’s creation is sacred, and not just the inner sanctuary.”

Further north in Vaughan, the Jewish environmental group Shoresh – meaning “root” in Hebrew – developed Kavanah Garden containing 100 varieties of organic vegetables, herbs, fruits and wildflowers. By running workshops, camps and field trips for schools and synagogues on food justice, Kavanah Garden helps communities return to their Jewish roots. Risa Alyson Cooper, Shoresh’s executive director, holds out the promise of Tikkun Olam, a Jewish concept that suggests humanity has responsibilities to heal that which is broken in the world. In this case, it is our modern food system to which she is referring, one that “hides the environmental, social and health costs.”

In 2007, the Unitarian Church of Calgary decided to become a “green sanctuary.” They now promote environmentally conscious lifestyles, and address environmental problems and injustices. In April 2015, along with others from Calgary, they lobbied the government to take “serious action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and develop clean, renewable energy.” Their motivation: a Unitarian’s spiritual quest involves a deep relationship with Earth.

The Catholic Sisters of Charity of the Immaculate Conception joined hundreds of local residents of Red Head, New Brunswick, in May 2015 to march and protest against the proposed Energy East pipeline. They say that their faith commits them to social and ecological justice, considering the Earth to be a “respected commons shared with

all creation.”

These initiatives are part of a larger movement within the Canadian religious scene that is increasingly placing environmental issues and actions at the forefront of deliberations on faith. The initiatives range in scope and commitment, from a Muslim community cleaning up Herring Cove Provincial Park in Halifax, to complex, long-term undertakings, such as Shoresh and St. Gabriel’s, which require extensive capital expenditures and considerable support from the faith community.

They share a rationale for addressing environmental issues informed by a religious perspective. They are usually not environmentalists who happen to be religious, but rather religious people imbued with a heart-felt and ethical obligation to care for Earth. In fact, most, if not all, mainstream religions in Canada are engaged, in one way or another, in responding to ecological issues.

After 10,000 people marched for climate justice in Toronto, 150 interfaith representatives gathered, including Buddhists, Muslims, Jews and Christians.

Although not a religious organization per se, an examination of religion and ecology within Canada would not be complete without reference to the Earth-honouring spirituality of First Nations peoples. Arguably more so than any of the mainstream religions in Canada, First Nations peoples maintain a profound spiritual connection to all creation. Described as a living entity, “Mother Earth,” guides Indigenous peoples in all their deliberations on the environment, which they believe they have a special responsibility to protect and foster respect. The Assembly of First Nations maintains an Environmental Stewardship Unit that focuses on ecology at the local, regional, national and international level.

Most of the religions in Canada, including the Assembly of First Nations, often collaborate with ecumenical or interreligious environmental organizations and alliances. Faith and the Common Good, for example, is a national interfaith network whose Greening Sacred Spaces program assists faith communities on the spiritual, as well as practical aspects of energy audits, divestments, retrofitting or finding ways to reduce their footprint. Fossil Free Faith works as a consortium of many faiths from across Canada to invest in sustainable energy options. Many other ecumenical organizations (such as The Canadian Council of Churches, KAIROS Canada, and Citizens for Public Justice) make environmental advocacy part of their work on justice. Some religious organizations work with environmental networks like the Climate Action Network to further their advocacy.

At the academic level, most religious studies or theology departments at universities offer courses or programs on religion and ecology. Professors and students are gaining expertise in the larger and internationally recognized field of religion and ecology. At St. Thomas More College, University of Saskatchewan, for instance, students can explore the “issues of complicity, responsibility, guilt, reconciliation and restoration in human-Earth relations.” At the Faculty of Theology, University of St. Michael’s College in Toronto, students can receive basic and advanced degrees in “ecotheology” through the Elliott Allen Institute for Theology and Ecology.

While this portrayal of religions and ecology in Canada might impart a sense that religions in Canada are fully engaged in environmental issues, this is not the case. A deeper analysis reveals that community actions are often the exception. On a national and collective level, religions in Canada are not stepping up to the plate on ecological issues in a consistent and collective manner. What might account for this limited, albeit passionate, response?

First off, not all religions have centralized, national authoritative structures that speak for members, such as Judaism and Islam. Some traditions (the Roman Catholic and Evangelical Christian Churches, for example) tend to focus their national advocacy work on religious doctrine and sexual behaviour, such as abortion or gay marriage. Several religious organizations that work on ecological issues, such as KAIROS, are not directly connected to congregations. Religious membership is declining – with the exception of Islam and some evangelical groups – which reduces financial assets. Also, many churches have experienced financial stress from lawsuits. Finally, overall, Canadians are often politically apathetic on ecological issues.

There are more complex reasons that have to do with thinking through the intersection of ecology and religion. Internationally, the work of engaging religions on ecological issues has grown into a significant force in both academic study and religious practices. Transformations are occurring in most religions’ traditions throughout the world. Understanding the extent of the ecological challenges to religion varies. For some, it is retrieving, re-evaluating and reconstructing of religious traditions to find insights for ecological stewardship. For others, it is evident that religions themselves are in transition.

What is more, the humanities have brought forth attentiveness to values, knowledge production, power, symbolic consciousness and postcolonial and postmodern epistemologies, which have unsettled stable meanings of “religion.” Owing to the extent of the ecological crisis, as well as to knowledge of evolution, Earth sciences, physics and cosmology, it is evident that religions are challenged to reinterpret themselves. Both epistemological revolutions as well as planetary transformations are occurring. These are compelling an immense transformation of religions. Many recognize that humanity, along with all our reflective traditions and orienting worldviews, must move towards a planetary vision in order to realize the limits of the natural world. These efforts represent massive internal transformations of religious interpretations and frameworks.

WHAT IS ECOTHEOLOGY? Ecotheology is rooted in the premise that a relationship exists between human spirituality and the state of nature. It recognizes the current debilitating degree of nature’s degradation, and identifies potential solutions from a sustainability and ecosystem management perspective. This builds hope and inspiration to the ethics of any religion. If we want to address the global environmental crisis, a conceptualized higher belief system is required to inspire the change necessary, and alter the way society currently operates. Ecotheology encourages all religions to explore the interconnectedness of spirituality and ecology. It heavily focuses on how, to our peril and to an escallating degree, humans in this and last century have tried to dominate nature. To address our planetary crisis, ecotheologians study and restructure religious practices to incorporate ecology into the moral systems embedded in their traditional practices. This integration catalyses ecotheological practice into action at both a local and global scale. – Kassidy Veenstra

On the ground, faith communities and religious adherents are engaging in ecological issues through many contexts. The Forum of Religion and Ecology at Yale University attests to initiatives around the world on water issues, food security, climate change, ecojustice, toxic waste and pollution. This could be as simple as adding these concerns to prayers and rituals to political lobbying and social activism.

Noticeable change is stirring in religion and ecology in Canada and elsewhere as religious leaders increasingly raise ecological concerns. Hundreds of statements, activities and documents attesting to this are available at the Forum on Religion and Ecology. The recent Encyclical by Pope Francis, Laudato Si’ (Praise Be), is intended to appeal to all peoples of faith. The encyclical affirms ecological literacy, encourages scientific knowledge, recognizes climate change and promotes ecological stability. It connects consumerism and ecological ruin, Western lifestyles and global South injustices, and it notes the connected destruction of ecosystems and human communities. The document criticizes political apathy, and urges citizen mobilization and government responsibility towards ecological health.

Greater concern is particularly evident concerning citizen’s movements demanding action on climate change. Over 200 signed the faith leaders’ declaration on climate change that begins, “As faith leaders, we believe that unchecked climate change is one of the greatest threats to peace and prosperity for our world.”

International pressure is mounting with organizations such as The People’s Climate Movement, the World Council of Churches and Faith in Public Life. In preparation for COP21 in Paris, citizens groups mobilized around the world, organizing conferences, workshops, protest and marches. In July 2015, after 10,000 people marched for climate justice in Toronto, 150 interfaith representatives gathered, including Buddhists, Muslims, Jews and Christians. Most religious organizations launched projects last year around climate change in light of COP21. A few examples are the Assembly of First Nations’ Regional Indigenous Peoples and Nations Consultation on Climate Change: Defending our Rights and Defining our Priorities on the Road to Paris and Beyond; the United Church of Canada’s Take Action Now on Climate Justice; Canadian Mennonites’ Pilgrims of climate justice plan; Islamic Relief Canada launched the Islamic Climate Change Declaration; Canadian Council of Churches’ Justice Tour 2015: Churches focus on climate change and ending poverty; and Citizens for Public Justice that offers extensive information and resources to religious communities.

A concerted effort by the religions in Canada could prove to be influential. Religion and ecology must wade into the political fray. The resistance to religions becoming global political players for ecological democracy does occur, as it is a challenge to the corporate and/or militarized state. However, if religions remain depoliticized, they will have little transformative power. Religious institutions have access to myriad communities and can encourage politically active citizens.

The collective perception is that we live at the edge of an era, facing challenges of a type and magnitude not faced previously by human communities. There are multiple causes and uncertain solutions. Political will and religious communities are required. Climate change, for instance, is not just a matter of policy, economics or technology. It is a moral issue and for many, it is a spiritual issue, as connections between the natural world and the sacred are primal. We cannot, then, expect solutions to come from policy makers, financial markets and scientists alone. Religions, although fraught with ambiguities, carry great potential for fostering social change, living within limits, promoting justice, awakening awareness, and developing an ecologically sane and just way of life.

Heather Eaton is a professor at Saint Paul University. She has a PhD in ecology, feminism, theology and religious pluralism. Her recent work looks at religious imagination, evolution, Earth dynamics, peace and conflict studies on gender, ecology, religion, animal rights and non-violence.

Simon Appolloni is a sessional instructor at University of Toronto and Humber College, teaching in the areas of environmental studies and religion. His research focuses on human-nature-relationships, and the ethical dimensions of sustainability.