Despite all the traffic, you won’t find road rage in Southeast Asia. It doesn’t exist, largely because there’s an entirely different culture of driving. Something we in the West need to learn.

We North Americans live with road rage. We get mad when we’re stuck in traffic, if someone cuts in front of us: if anyone impedes us while driving. Other drivers are the competition, even the enemy.

This is not the norm in other countries. We noticed changes in driving habits as we made our way across Europe. We felt at home on the roads of France and Italy, but could sense subtle differences. The French were accommodating, but would let us know their displeasure if we were hesitant or slow. In Italy, every second counts. There, drivers would accelerate past us only to brake for the upcoming exit.

Things started to change in Greece, where lines on the road became optional. On a two-lane road with a paved shoulder, you were expected to drive on the shoulder to allow cars to pass in the middle. Two lanes became three. It sounds dangerous, but it works because all drivers do it. There was no road rage.

Then came the culture shock of India. On our first day in Trivandrum we spent ten minutes crossing a road, waiting for a gap that never came. We finally made a dash to the middle before reaching the other side. There were no sidewalks, so we walked along the roadside, picking our way around the motorcycles and auto rickshaws blocking our way. And the noise! Everyone honked their horns incessantly. I jumped each time a horn sounded behind me, thinking, as a North American, that someone wanted me out of their way.

Eventually, we began to see a rhythm and logic to driving in India. Horns are not used in anger; they’re a form of echolocation. Indians drive with their ears as well as their eyes. Horns simply mean: “I’m here, watch out for me,” or “I’m on your right and about to pass.”

City traffic in India is a swarm of motorbikes, bicycles, auto rickshaws and cars. If they followed North American rules of the road, everything would quickly mire in permanent gridlock. Instead, things flow, though sometimes very slowly. Be patient, make no sudden moves, take your turn and let others in: it works because there is absolutely no road rage. When someone tries to pass, or cut in front of you, you let them. There’s always room for one more.

Highway driving in India: the van at right has moved over to make room for the bus

On the country roads in India, all semblance of respect for the white lines disappeared. Cars would overtake and flash their lights at oncoming traffic, which would move to the shoulder to make way. It’s a fine art to know who is dominant. To the untrained Western eye, it’s madness, but if you have grown up with it, it’s normal.

By the time we hit Southeast Asia, we could dance our way across any street. Visualizing the flow of traffic and sensing gaps between the trajectories was a breeze. Crosswalks have no meaning; you just make your intentions known and drivers adjust for you. Scooters and small motorbikes rule the road in Cambodia and Vietnam where whole families fit on a scooter. Young children ride bicycles on the street. Our Western notions of safety are thrown for a loop, and yet it works because the culture is accommodating, affecting how people drive. There is no speeding on city streets, no aggressive driving — just people going from point A to point B.

When we landed in Bali, I no longer felt safe on the roads. Bali is the intersection between West and East. Its strong traditional culture is mixed with decades of development as one of the world’s premiere tourist destinations. Narrow roads run through canyon-like streets of villages with high concrete walls and few sidewalks. There’s a greater air of urgency here, faster traffic and more cars mixed with scooters.

My feelings of unease were well founded. Traffic deaths in Bali are alarmingly high. In 2011, 758 people died in road accidents over a three month period. An anomaly perhaps, but the travel websites are full of cautionary notes about Balinese roads.

As I write this article, we are in Australia, a country which despite being on the other side of the world, is remarkably close to Canada in population, politics and culture. Impatient drivers honk their displeasure – just like at home. An Australian current events comedy show, The Weekly, ran a piece on cyclists and road rage, which, except for the accent, could have been done in Canada.

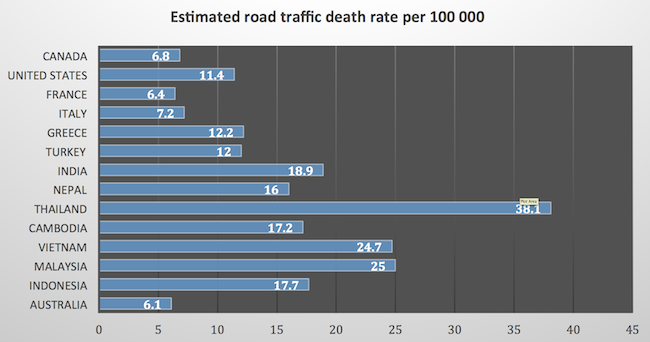

It seems strange that I should feel safer riding a bicycle in Hoi An, Vietnam, than I do on the streets of Toronto, especially when the stats would point to the opposite being true. In 2013, the World Health Organization, with funding from the Bloomberg Philanthropies, produced a report on global traffic deaths. The report has some telling statistics on the deaths per 100,000 people in North America and the countries we have visited.

India and Southeast Asia have far more dangerous roads than North America or Europe, according to the report. And Thailand tops the list of unsafe roads in all the countries we have travelled through.

Bloomberg Philanthropies has committed $125-million over five years promoting road safety in 10 low and middle income countries that make up almost half of road-related fatalities, including Vietnam, Cambodia and Turkey. Their approach is to work with local governments and non-governmental organizations to improve road infrastructure, road safety laws and public education.

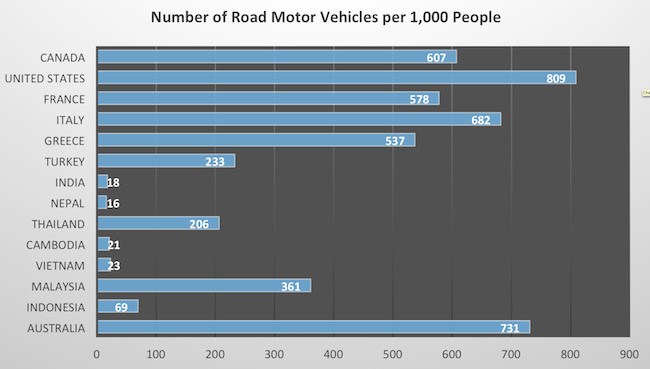

But there is another factor contributing to road safety: the type of vehicle. I’m not referring to vehicle design or the ability to afford a high end SUV instead of a second-hand clunker, but to the very basic decision between a motorbike and a car. As the statistics on motor vehicle ownership shows, a car is simply not an option for the vast majority of people in many countries.

Poorer countries, like India and Vietnam, may have fewer cars per capita, but they are awash in motorcycles and scooters. Thailand and Malaysia, both of which are more affluent countries than their neighbours in Southeast Asia, have considerably more cars on the road. From what we saw of Malaysia, it is an oil rich country that has invested in roads and highway infrastructure, which may help account for its better traffic safety record than Thailand.

The fine balance between affluence, infrastructure, and culture begins to emerge: the hazards of high speeds and risk-taking on rough rural roads; the traffic ballet in the urban bedlam of India and Southeast Asia; and the intolerance of cocooned car drivers in affluent countries. It’s all connected, especially the cultural aspect. With the right attitude, there’s room for everyone.

Night time traffic in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

The simple lesson here is that we, in Canada, have the wrong cultural approach to driving. Like Australia, we pride ourselves on being a warm and friendly country. We should apply these values to our behaviour on the road.

The deeper lesson is that this relationship between affluence, infrastructure, and culture is playing out in our response to climate change, resource exploitation, and sustainability. Our affluence is accelerating the decline, we lack the infrastructure of sustainability, and the anger of road rage is entirely consistent with the anger of denial.

Traffic accidents pale against the ecological genocide we are inflicting on the planet, and we desperately need to shift our cultural response.

The former executive director of the Conservation Council of Ontario, Chris has started a new initiative to help Canada transition to a sustainable future by “living better with less,” Canada Conserves. After 30 years in the environmental movement, Chris Winter is on a well-deserved round-the-world sabbatical with his family. Along the way, Chris will be sharing examples of how other countries are dealing with climate change, resource scarcity and economic turmoil. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook. You can also follow the family’s Hello Cool World tour blog.