THIS ISSUE STARTS with a call to action. We propose that Canada’s housing system needs a reframing – and that’s putting it lightly. As a nation, we pride ourselves on being inclusive, friendly and compassionate people. But our housing situation does not reflect these values. Growing numbers of people are on social housing waitlists; the homeless population is increasing; the state of housing for Indigenous communities remains abysmal; and the growing concern among millennials about their ability to afford housing is making headlines almost daily.

THIS ISSUE STARTS with a call to action. We propose that Canada’s housing system needs a reframing – and that’s putting it lightly. As a nation, we pride ourselves on being inclusive, friendly and compassionate people. But our housing situation does not reflect these values. Growing numbers of people are on social housing waitlists; the homeless population is increasing; the state of housing for Indigenous communities remains abysmal; and the growing concern among millennials about their ability to afford housing is making headlines almost daily. It is not enough to acknowledge and regret these problems. We need to act in a meaningful and lasting way to fix them.

Trends suggest we are no longer living up to promises of a nation that translates its care for the social welfare of its people into actual policy and programs. The solution is, in part, about putting our money where our mouths are.

In the 1990s, the federal government slashed budgets for social and affordable housing programs. While some new programs have been rolled out since, the combined efforts of all levels of government are still not making up for the loss of the strong role the federal government once played in delivering housing to Canadians.

We need to re-introduce housing programs and think differently about what housing means to us as a nation and to the diversity of people within it.

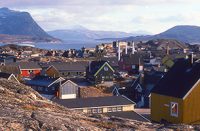

Housing certainly means “house” and “shelter,” but is also means “home.” Taking many forms – from single-family dwellings to townhouses and other multiplexes, to apartments on the ground and high in the sky – the house is a gateway into local communities and Canadian society. It is where families are raised and life events both good and bad unfold; it is where cookies are baked, meals are shared and memories are made. Some homes have been with families for centuries, while some offer the promise of a new beginning. Homes give us a sense of belonging, security and identity.

However, Canada is changing, and with these changes come the dire prospects too many people in Canada now face in their ability to afford housing, and ultimately make a home. Canada’s population is getting older, household sizes are getting smaller, and environmental challenges are mounting. Housing prices in our major urban centres continue to outpace inflation and increases in wages, pushing ownership and rents beyond the reach of many, especially young families and professionals entering the workforce.

We are no longer living up to the promises of a nation that translates its care for the social welfare of its people into actual policy & programs.

How do these changes impact the way Canadians are housed? If home prices are going through the roof, are there ways to make housing more affordable for more people? How is the existing housing stock – some 13 million homes and units in-progress in Canada – responding to an increase in single-person households and smaller families? While the environment figures prominently in the list of issues important for many Canadians, has the building industry adequately responded to these changing concerns? What role should housing play in achieveing the goals of the Paris Climate Accord? As Canada, already one of the world’s most urbanized countries, continues to see an increase in its urban population – especially among young people – how are existing and new city-dwellers to be housed?

The good news is that conversations about housing as an issue of national importance have been on the rise. In the 2015 Federal election, housing was mentioned in candidates’ campaigns across the political spectrum. Unfortunately, this conversation has been largely limited to cost of ownership, the perennial possibility of a “housing bubble,” low interest rates and other financial incentives – as well as the latest trends in kitchen and bathroom designs.

While all valid considerations, these conversations do not tell the whole story about Canada’s housing system. They reflect on a housing system that is, rather than a housing system that could or should be. This issue of A\J is the beginning of a larger and deeper conversation about housing. We cannot address everything relevant to housing or offer the solution to Canada’s growing housing problem in one issue. We ask as many questions as we provide answers to. This is the beginning of a conversation that aims to stimulate thinking – for thought is, as Freud once said, action in rehearsal.

SEAN HERTEL is an urban planner, who takes the road less travelled when it comes to his consulting practice. With any project, he infuses social justice into his passion for cities. Sean leads a Toronto-based professional planning practice specializing in land-use policy to support transit, intensification and housing affordability. He is a frequent speaker and university lecturer, and conducts suburban and social equity research at the City Institute at York University (CITY). @Sean_Hertel

MARKUS MOOS is a faculty member in the School of Planning at the University of Waterloo. Markus is associate director, Graduate Studies, and professor in the School of Planning at the University of Waterloo. His research is on changing housing markets, generational change, youthification, and the economy and social structure of cities. He lives in Kitchener, Ontario, with his wife and three-year-old daughter. @Markus_Moos