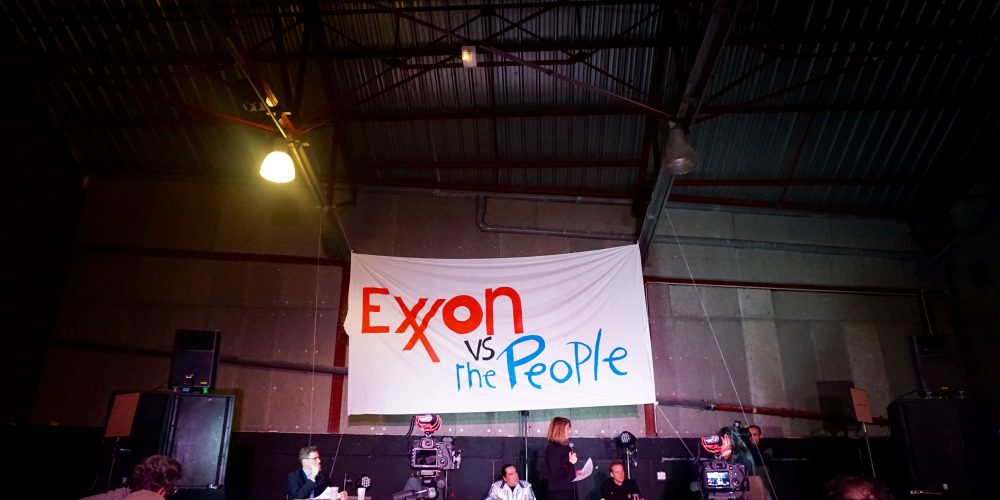

There was nothing “mock” about it. Canadian journalist Naomi Klein and American founder of 350.org Bill McKibben served as co-council in the trial of ExxonMobil. One of the biggest oil companies is the world was put on trial in Paris for crimes of deception. Investigations earlier this year revealed that ExxonMobil has known about the implications fossil fuel use on the climate and actively suppressed that information.

There was nothing “mock” about it. Canadian journalist Naomi Klein and American founder of 350.org Bill McKibben served as co-council in the trial of ExxonMobil. One of the biggest oil companies is the world was put on trial in Paris for crimes of deception. Investigations earlier this year revealed that ExxonMobil has known about the implications fossil fuel use on the climate and actively suppressed that information.

Though not a legal trial, Klein said the event, which was part of The People’s Climate Summit, was a preview and that the “prosecution of Exxon will happen in real courts very very soon.”

“We cannot get back much of what we have lost because of the lies, because of the intransigence, because of the sabotage … but we can demand justice, we can demand reparations, and we can demand action and that is exactly what we intend to do,” Klein said.

Though not a legal trial, Klein said the event, which was part of The People’s Climate Summit, was a preview and that the “prosecution of Exxon will happen in real courts very very soon.”

Witnesses at the trial included Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner, an activist and poet from the Marshall Islands; Joydeep Gupta of Third Pole Network; journalist Antonia Juhasz; Cindy Baxter, a co-founder of ExxonSecrets; climate scientist Jason Box and Social Action Nigeria member Ken Henshaw among others.

The Marshall Islands in the Pacific Ocean are only one metre above sea level and therefore are deeply affected by the rising sea levels that climate change has caused in recent history. Jetnil-Kijiner said that a grave site on one of the islands is being washed away with the sea and levels rise and storms become more harsh. The more than 70,000 inhabitants of the islands are in danger of becoming climate change refugees due to increasingly rising tides.

“If we lose our land, we lose our identity, we lose we are as a people,” Jetnil-Kijiner said during her testimony.

The connection between land and identity is felt in many climate change-affected communities across the globe. Faith Gemmill, executive director of Resisting Environmental Destruction on Indigenous Lands, testified to the drilling in arctic communities, where only five percent of coastland remains protected. Exxon is still trying to drill on that land.

“When I say we subsist from the land, it’s not just about food security. It’s about our culture, our spirituality, our economy, everything we are as a people is tied to the land … any disruptions affect us and the very social fabric of our communities,” Gemmill said. Walking along Prince William Sound in the Gulf of Alaska where the Exxon Valdez oil spill occurred in 1989, Gemmill can still see the aftermath. “You lift a rock in certain areas and there is still oil and it’s still fresh and still smells as if it was spilled yesterday.”

“It’s incredibly disingenuous what Exxon became because the science they were doing in the 80s and 70s was state of the art, it was very well-funded. I’ve read the reports, the clarity of that science is top notch and they turned it into secrecy and even suppressed their own scientists,” said Jason Box, a climatologists studying the Greenland ice sheet.

In the late 1970s, James F. Black, a senior scientist with Exxon told company executives that research demonstrated that the carbon dioxide released from the burning of fossil fuels was humankind’s biggest contribution to altering the climate.

Box said the problem is not just Exxon, but the system it works within that does not want to fairly price fossil fuels. “We publish thousand page reports and it feels like no one is listening,” Box said.

In the late 1970s, James F. Black, a senior scientist with Exxon told company executives that research demonstrated that the carbon dioxide released from the burning of fossil fuels was humankind’s biggest contribution to altering the climate.

“We will be paying for that for decades to come,” Box said of Exxon’s suppression of that science. Black’s 1978 summery of his climate research said there was a window of five to 10 years before “hard decisions” regarding altering our energy use would become critical.

Had Exxon acted on their findings in a way that respected the environment, they could have led the world on a road to sustainability Box said. They could have become an energy company rather than fossil fuel and could have financed clean energy decades ago. “Morally, we all have to make our own judgements individually … I think it’s a game-changer politically,” Box said.

“We have heard stories of the most reckless and discriminatory disregard for human life and human well-being and human health. It is Exxon’s crime that it believes that money trumps life,” Klein said in closing arguments.

Ultimately the trial ended with a request for courts to do what this mock court could not: call Exxon to speak to its crime and hear the testimonies of those affected most by climate change.

Last month, the oil giant was issued a subpoena from the New York State Attorney General to hand over the four decades of research and communications about climate change.

Megan is A\J’s editorial manager, a lover of journalism, and graduate of the University of Waterloo’s Faculty of Environment.