Nancy Holmes, a professor in the Faculty of Creative and Critical Studies at the University of British Columbia Okanagan, is to be congratulated for this plump and sumptuous anthology of English language Canadian nature poetry.

Nancy Holmes, a professor in the Faculty of Creative and Critical Studies at the University of British Columbia Okanagan, is to be congratulated for this plump and sumptuous anthology of English language Canadian nature poetry.

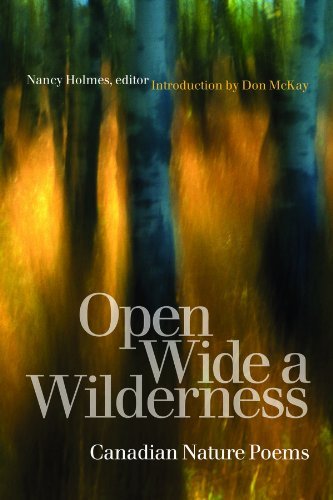

In Open Wide a Wilderness, two centuries of poetry by over 190 poets are assembled in only 510 pages. Although it enjoys little mainstream attention, Canadian poetry is strewn throughout the myriad inconspicuous little seeps and rivulets that feed the watersheds nourishing our national literary culture. It’s found in the colourful archipelago of small presses across Canada (including Turnstone, Black Moss, Thistledown, Porcupine’s Quill and Oolichan).

Holmes provides a panoramic sampler of poems that explicitly address what she calls “wild nature.” The selections reflect shifts in subject matter over time, changes in style, differing perspectives and recent developments such as environmental concerns and eco-poetics. Themes deal with both the love and fear of nature; pristine solitude as well as the wild as a place of work; masculinist incursions by the likes of Robert W. Service venturing into the Klondike; and more recent ecofeminist sensibilities such as S.D. Johnson’s serene meditation on watching two magpies feeding on a dead gull: “The gull is meat – its mother / is oblivion. / The sisters nod and nod, the gull / is good food. / They’re tearing it / into pieces of heaven.”

Holmes’ collection includes well- known works by “canonized authors,” such as Archibald Lampman, E. J. Pratt and Al Purdy, as well as “strange and lovely poems” by forgotten or almost unknown poets. About half the book is devoted to poets born between 1930 and 1960, many of whom collected national awards along the way, including Lorna Crozier, Michael Crummey, Anne Szumigalski, Tim Lilburn and Anne Simpson.

I find it very satisfying to discover fine poems that I never knew existed. I got a belly-laugh from Bill Bissett’s idiosyncratically spelled “Othr Animals Toys,” marveled at the subtle rhyming of Newfoundland cabinet minister Gregory Power’s “Bogwood,” written in the 1930s, and was haunted by Robin Skelton’s möbius strip “Stone-Talk.” Robert Bringhurst’s “Anecdote of the Squid” provides wry propositions (“But the squid may be said / for instance, to transcribe / his silence into the space / Between seafloor and wave”), while Susan Frances Harrison’s 1928 whirl- wind, “A Canadian Anthology,” takes you on a rhapsodic taxonomic tour de force through a woodland ecosystem.

The volume begins with an essay by Governor General prizewinner for poetry Don McKay, in which he sketches out some important themes in Canadian nature poetry. One is the attempt to reach for the heart of nature – the “inap- pellable.” McKay reminds us: “A mystic who is not a poet can answer the inappellable with silence, but a poet is in the paradoxical, unenviable position of simultaneously recognizing that it can’t be said and saying something.” He also discusses the Canadian obsession with finding a “sense of place” – proposing that we discover our place within nature, rather than trying to claim our own piece.

McKay, an experienced student of nature, argues that poets should also study nature’s particulars: “… artists of language – that is, poets – are also called to develop the sense organ that language listens with, to ensure that, as the effects of environmental degradation become more evident in decades to come, it is attending at a deep level. Even if, when it moves from listening to speaking, all it can utter is elegy. Even if it is all lament.”

Readers who aren’t literary scholars may find McKay’s essay tough going, but it is worth persisting. I suggest tackling the essay straight on while making excursions into the poems he mentions within the volume. They will illuminate his observations. Once outfitted with McKay’s literary binoculars, you can start exploring the anthology in earnest.

The book includes a superbly organized subject index, which I used as a trail guide. It worked equally well to locate poems about everything from my favourite beast, the sturgeon, to perceptions of nature and love, mining or sad tales about pollution.

This beautiful anthology begins hugging you very quickly. Read Open Wide a Wilderness for refreshment and discovery, for epic journeys into the minds of insects and the lives of flowers, to rejoin your totems and familiars, and to rekindle your resolve to continue the good fight. Keep it close at hand in case you wake up lonely at night – and when you crave solitude. Read the poems aloud to your friends and sing them to the river.

Open Wide a Wilderness, ed. Nancy Holmes, Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2009, 510 pages

This review originally appeared in Out of the Box, Issue 36.4. Subscribe now to get more book reviews in your mailbox!

Reviewer Information

Greg Michalenko is a member of Alternatives Journal’s editorial board.