Almost 70 years ago, the United Nations declared adequate housing to be a fundamental human right, yet over a billion people lack this right across the globe. Canada’s status as a high-ranking country on global human development and liveability indices should imply that adequate housing for all has long been achieved here. However, a visit to most First Nations reserves, high-poverty neighbourhoods or some ethnic enclaves provides significant evidence to the contrary.

Almost 70 years ago, the United Nations declared adequate housing to be a fundamental human right, yet over a billion people lack this right across the globe. Canada’s status as a high-ranking country on global human development and liveability indices should imply that adequate housing for all has long been achieved here. However, a visit to most First Nations reserves, high-poverty neighbourhoods or some ethnic enclaves provides significant evidence to the contrary.

While many Canadians are relatively well housed, we lack adequate housing for low-income families, individuals with mental illness and disabilities, seniors, Indigenous people, and recent immigrants and refugees. This is not just an issue of inadequate shelter. Beyond meeting basic needs, having a home and a community by extension is a precursor to a myriad of social, economic and health benefits. This is true for all people but in particular for international migrants whose top priority, even before securing employment, education and access to health care, is locating housing.

The link between economic well-being and adequate housing is well-documented and often central to policy arguments for improved housing in this country. What is less prominent in these discussions are the health and social co-benefits promoted through regulatory and policy frameworks supporting adequate shelter for all. For instance, as a social determinant of health, poor housing conditions

have been linked to higher mortality and morbidity rates directly (e.g., asbestos, radon, lead in dwellings) and indirectly (e.g., stress associated with lack of financial resources and crowded living conditions).

Inadequate housing is correlated with many social disadvantages including social exclusion, poor education outcomes in children, food insecurity, and reduced quality of life. Further, for Canada’s large immigrant and refugee population, securing adequate housing is a marker of successful integration and a first step toward building a sense of belonging and community.

The Canadian government’s highly politicized commitment to resettle 25,000 Syrian refugees by the end of February 2016 – with the expectation of thousands more to come in subsequent months – brought Canada’s housing issue to the forefront of political debates, at least as it relates to immigration and resettlement. Citizenship and Immigration Canada temporarily paused the arrival of the refugees in Halifax, Ottawa, Toronto and Vancouver at the request of settlement agencies who were dealing with a housing backlog. One immigrant agency stated that incoming families were larger than expected and finding housing with a sufficient number of rooms was a challenge. Many of the newly arrived refugees in Toronto have been living in hotels for months as settlement agencies scramble to find adequate housing.

The concept of sense of place – the emotional connection between people and place – is also evident in popular culture. Rappers from neighbourhoods like Los Angeles’ Compton and New York’s Harlem are proud to sing about these roots.”

This situation is not unique to the Syrian refugees – past research acknowledges that many newcomers are poorly housed in the early years post-migration. For instance, a 2012 study using the Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada found that recent immigrants living in Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver spend two to three times more of their total income on housing compared to the general population, in large part due to their low income status. Many spend years in precarious employment circumstances impending entry into the expensive real estate market in Canada’s largest cities.

Further, immigrant families are four times more likely than the Canadian-born populations to live in crowded conditions. This same study found a marked improvement in newcomers’ housing conditions over time as their incomes increase and home ownership became a reality.

However, this experience is not evenly distributed across the newcomer population. At a greater disadvantage are refugees, who often have limited financial and social resources. In addition, visible minorities, which make up a large portion of the total immigrant population, experience discrimination in the housing market.

As immigrants continue to make up a growing portion of Canada’s population, the impact of the current housing circumstances needs to be at the forefront of the policy agenda in order to facilitate social integration. When I speak of integration, I am referring to broader feelings of inclusion and belonging as an addition to the more pragmatic and conventional markers such as home ownership. Social inclusion as a marker of integration goes beyond actions that emphasize the “doing”, such as entering the labour market and buying a home, to those focused on “being.” That means building strong, diverse social networks, participating without barriers in social and political events, and benefitting from the rights and freedoms provided by Canadian legislation.

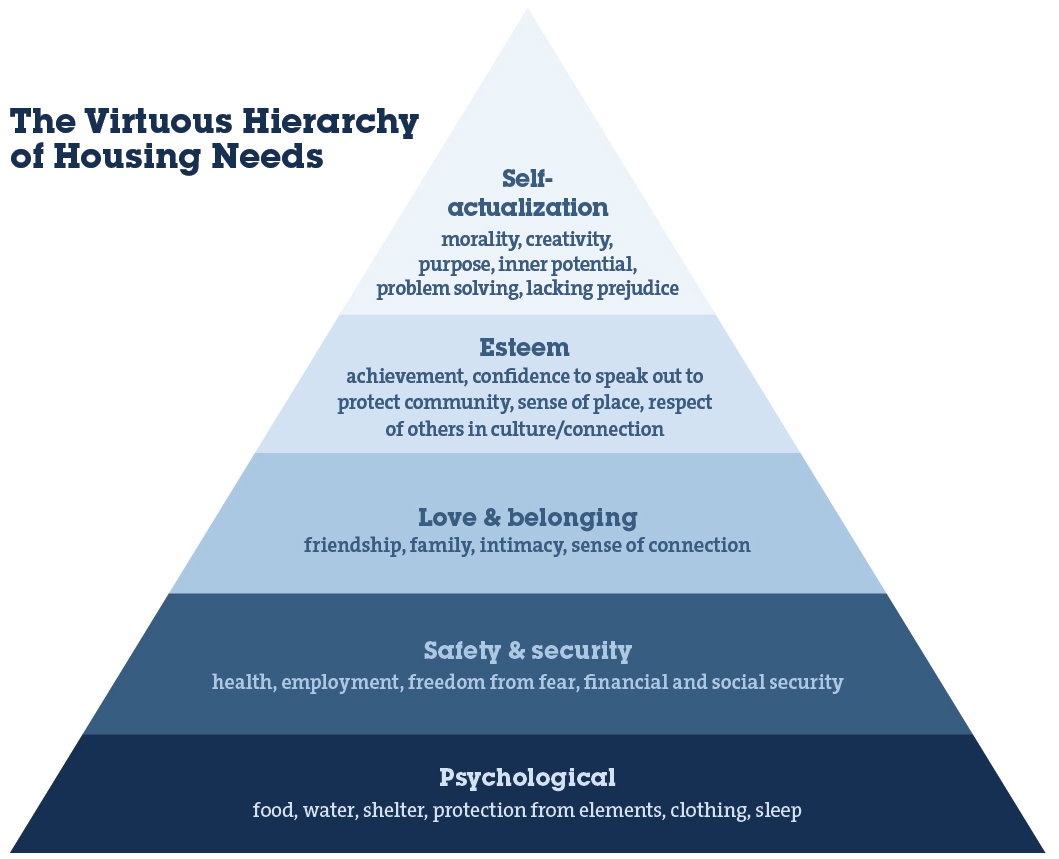

One way to think about housing and integration is through the work of Abraham Maslow, the psychologist behind the hierarchy of human needs. Self-actualization and personal growth are at the top, and basic necessities like food at the bottom. Housing has traditionally been confined to the bottom level of the pyramid as it meets the basic physiological need for shelter and protection from the elements. Housing affordability is most important to this level as it is connected to other basic needs such as food.

But shelter is only the tip of the iceberg for how housing impacts our lives. Moving up Maslow’s hierarchy to the level of safety, including the need for personal, health and financial security, also has obvious connections to housing. Quality and suitable housing that is not overcrowded or in need of repair contributes to health and personal security. Financial security relates directly to housing affordability, whether through home ownership and building home equity, or the ability to contribute part of personal income to financial investments.

When we consider housing needs in a “Maslow’s Heirarchy of Needs” perspective, we shift our thinking from a house as simply a physical dwelling to a more meaningful concept of “home”. At its highest level, a home, whether rented or owned, becomes a structure that supports occupants who have a strong sense of place, and who have the confidence to creatively engage in their community.

However, it is the levels of Maslow’s hierarchy dealing with belonging and esteem that most closely relate to the broad understanding of integration and social inclusion. This is where thinking of housing as a physical dwelling that meets our basic needs of shelter and security shifts to the more nuanced and meaningful concept of home.

When a house is given positive meaning, it becomes a home. It is the place of family, connection, privacy and culture. For many, remembrance of their childhood home incites feelings of nostalgia, self-identity, rootedness and attachment. The sense of place – the emotional connection between people and place – is widely documented by researchers in a variety of disciplines.

This concept is also evident in popular culture. Rappers from neighbourhoods like Los Angeles’ Compton, and New York’s Harlem are proud to sing about these roots. Eminem’s “Imported from Detroit” commercial for Chrysler attempts to sell cars while simultaneously promoting the troubled city. Sense of place is so strong that residents return to communities devastated by disaster even when hazards are still present. Examples include New Orleans and Port au Prince where residents returned long before sites were declared safe to inhabit, or the residents returning to the highly toxic exclusion zone after Chernobyl’s nuclear disaster in the 1980s.

Sense of place is dependent on both personal and place-specific factors, and the emotional connection component is of course highly subjective. However, research has identified several predictors of attachment including length of residence and neighbourhood social ties, both of which recent newcomers lack. Some research suggest that authentic attachments may not be possible for newcomers based on their limited time in the area, their lack of contribution to the creation of that place and their identity as outsiders. Others do suggest a version of sense of place can be developed but not as easily by immigrants from diverse socioeconomic or political contexts.

In Canada, immigrants have long been a central part of nation building, though their participation has at times been the result of exploitive conditions, as in the case of Chinese railroad workers and Eastern European Prairie farmers. The creation of ethnic villages like Vancouver’s Chinatown and Toronto’s Little Italy include land uses and architectural designs that are reminiscent of pre-migration places of attachment. These ethnic villages create a form of physical and social belonging to both the past and the present while creating a future site of belonging for younger generations and future immigrants.

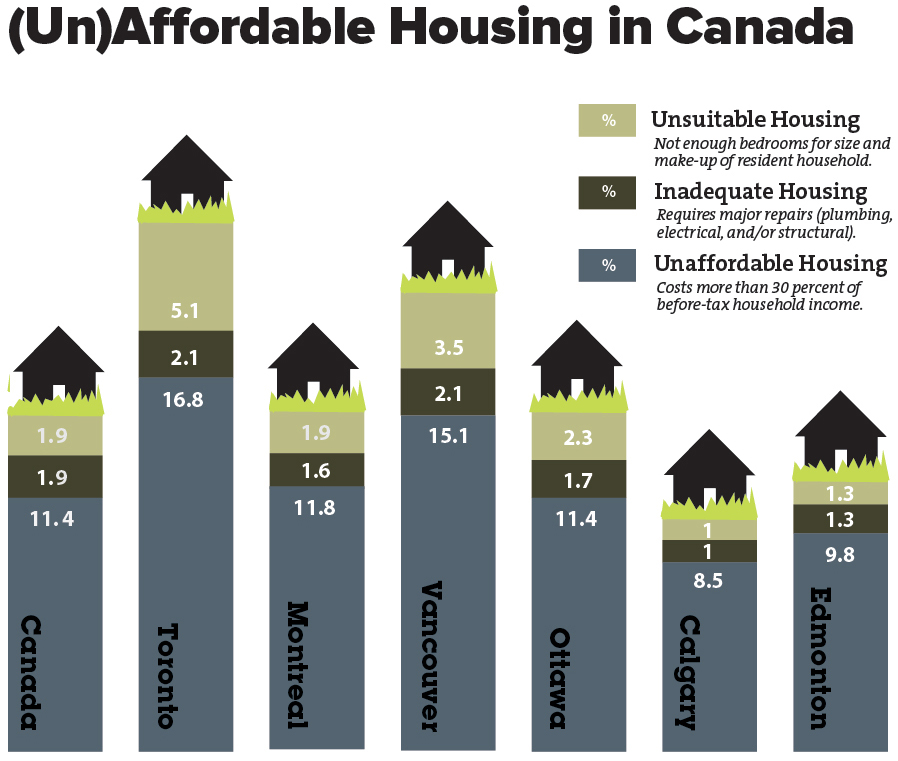

Toronto has the highest percentage of unaffordable housing at 24 percent total. Inadequate housing is correlated with many social disadvantages such poor education outcomes in children, food insecurity and reduced quality of life. Adequate housing improves health and social conditions, particularly for the most vulnerable part of our population (see “Housing Heals and Saves,” page 34). With respect to Canada’s immigrant and refugee population, adequate housing is a marker of successful integration and a first step toward building a sense of belonging and community. Chart by Maxx Hartt & Katy Belshaw; sources: Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation, 2006.

The rise of “monster homes” – large multifamily homes on smaller lots often incorporating culture specific architectural design – are ways in which financially capable immigrants foster attachment to their present location. These homes bring together both the physical (exterior design, internal layout) and social (extended familial ties) elements that foster a sense of belonging that is culturally specific, while also showcasing wealth and prestige in a way that builds a sense of self and identity in a new country.

Multiculturalism as a national policy is at least in theory well-suited to ease the transition and foster a sense of place and belonging for newcomers. It suggests that they can bring a piece of culture, language and identity with them, and build a sense of place and home that is a hybrid of values from both origin and host countries. In reality, this practice is often met with resistance. For instance, larger than “usual” homes built by Chinese immigrants in the 1990s produced tensions between newcomers and long-term residents in Vancouver and Toronto. It shows that there is a challenge to our acceptance of multiculturalism, particularly when it results in changing familiar environments that threaten the sense of belonging for long-term residents. This resistance is rooted in xenophobia.

Housing is an essential precursor to other settlement priorities for newcomers and a determinant of health and quality of life for all people. Thinking of ways that newcomers, and other inadequately housed populations, can be empowered to build their own community identities and sense of place is as important a consideration as the physical necessity of shelter. Innovative policy solutions should accordingly view the home as a source of inclusion and belonging for marginalized populations, and view home building as a precursor to successful integration in the short-term and nation building in the long-term.

Jennifer Dean is an assistant professor in the School of Planning at the University of Waterloo where she teaches and conducts research on healthy and socially inclusive environments.