A 2007 study by the Nebraska Energy Office demonstrated that when a 2500-square-foot home is constructed, on average 3.6 metric tonnes of waste is produced, all of which is shipped to landfills. Attributed to hotter than average summers, air conditioners, large emitters of chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) refrigerants, are also quickly becoming the norm in Canadian homes.

A 2007 study by the Nebraska Energy Office demonstrated that when a 2500-square-foot home is constructed, on average 3.6 metric tonnes of waste is produced, all of which is shipped to landfills. Attributed to hotter than average summers, air conditioners, large emitters of chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) refrigerants, are also quickly becoming the norm in Canadian homes.

In a society that is becoming increasingly aware of the human toll on the environment, it’s about time we re-examine our housing norms to lessen the impact of our shelter. The rise of large detached homes is supporting evidence of local action having a global impact.

The need to rethink design and construction practices of dwellings and align them with contemporary environmental constraints has taken centre stage in recent years. High-density urban configurations are now being regarded as a solution to some of the environmental consequences of sprawl, and governments have begun establishing standards for sustainable building practices. These standards go beyond national building codes, set stricter efficiency level criteria and act as accreditation systems. Builders and projects are qualified and distinguished according to the scope of their environmental pursuits. The US and Canadian Green Building Councils established the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program that has become the yardstick through which newly introduced residential projects are evaluated.

These trends and standards are an indication that commonly accepted home building norms are changing. The development of housing prototypes that can be constructed in higher densities is gradually taking hold. In addition, dwellings that conserve natural resources during construction, and energy after occupancy, are likely to be developed. With mounting energy costs expected, these efforts will appeal to builders and consumers alike.

The housing market is seeing more sustainable advances in building: “Net-Zero” houses that are capable of producing renewable energy equal to the amount of their consumption, solar-powered homes, innovative heating ventilation and air conditioning technologies, green roofs, healthy indoor materials, recycled products and water efficient systems. Still, in the highly conservative home building industry, which is notoriously slow to innovate, one can expect the passage of a decade or two before these technologies will become widespread.

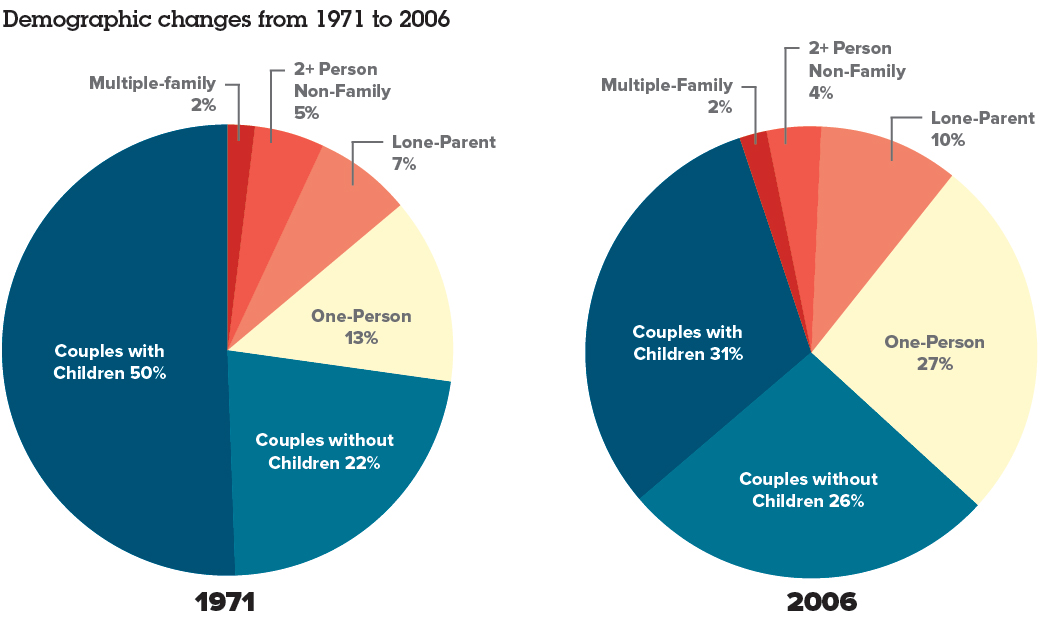

Between 1971 and 2006, there was a 31 percent drop in the numbers of married couples with children. Now, with more single people and single-parent househoulds, there is greater demand for small, easy to maintain, and affordable housing units. Source: Statistics Canada (Census of Canada).

Family transformations

Recent changes to the composition of the Canadian demographic have affected the way people live and house themselves. The post-Second World War image of the family made up of the breadwinner father, stay-at-home mother and three dependent children was so pervasive that home builders could easily – and successfully – view the bulk of their potential clientele as a homogeneous buying block. As the average Canadian household evolves and changes, so does the potential homebuyer.

In 1971, married couples with children accounted for 50 percent of all Canadian households, but by 2006 the number dropped to 31 percent. In parallel, there was an increase in the number of single person and single parent households – the number of single parent Canadian families has tripled in the past 30 years. The changing demographic make-up has also created a demand for small, easy-to-maintain and affordable housing units. It explains the increase in the construction of low-rise multi-unit dwelling types and apartment buildings in the heart of many large Canadian urban centres and, as of late, also in suburban areas.

Immigration is another factor impacting Canada’s housing market given global immigration trends, and one can assume an increase in the number of new arrivals. Traditionally, immigrants tend to flock to urban centres, which stand to increase ownership and rental costs in some cities and their edge communities.

As the average Canadian household evolves and changes, so does the potential homebuyer.”

Over the past 50 years, the average age of the Canadian population has been on the rise. Those aged 65 and over have seen their numbers more than double in the past 35 years, creating a market demand for seniors’ housing, which is expected to intensify as more Canadians join this age bracket. Some seniors will seek to trade their large, hard-to-maintain home for a smaller one.

A key consideration in selecting new homes is location. Mobility of Canadians, at least for part of the year, to places that enjoy comfortable year-round weather is expected. Proximity to basic amenities will be another key consideration. Seniors will look for an apartment next to medical services, near or above shopping hubs and transportation routes, leading to the increased popularity of transit-oriented developments. We can also expect an increase in the number of multigenerational arrangements and a growing demand for units in assisted living types of accommodations. Yet, the practice of aging in place where the aged will stay put in their old adapted dwellings is likely to become the norm for most.

The senior population, which was once considered marginal, has reached a critical mass, validating alternative approaches by policy makers, developers and architects to the design, construction and marketing of homes.

New economic realities

Economic fluctuations have taken a toll on society, impacting world markets and the lives of individual citizens. Secure employment and steady incomes are becoming less common. Lack of job security – and as a result, secure income – also makes it highly difficult for first-time homebuyers to purchase a dwelling in most large Canadian urban centres. In addition, an “affordability gap” has emerged, where the rate of house price increase has surpassed the rate of household income increase.

Property prices have risen three times faster than average salaries in the past decade. The widening gulf in affordability can be explained by a combination of the increasing scarcity of serviced land, higher infrastructure expenses, rising construction costs and simple market demand and supply factors.

In the past, first-time buyers sought large homes, which often overstretched their financial limits.The phenomenon is now more limited to the move-up market. Yet, following the 2008 global financial crisis, and due to an unstable labour market, a growing number of would-be homeowners can no longer accumulate the means necessary to buy a home, and as a result, the demand for less expensive, smaller homes is rising. It is expected that in the coming years, many first-time homebuyers will abandon the traditionally sought-after detached homes and have apartments as their first dwelling.

The home-building industry

A key question is whether the home building industry, in its present organizational structure, will be able to respond effectively to these emerging trends. To answer the question, one needs to be familiar with current Canadian home building practices. According to Clayton Research Associated Limited, some 85 percent of all low-rise dwelling units are constructed on-site – “stick-built” (vs prefabricated or modular).

The business model that characterizes this industry has evolved into a streamlined, concise system of operation. Many of the building firms involved in the production and delivery of housing are small, locally based and often family-owned operations. Many companies have only five or fewer employees on payroll and the majority of the building work is sub-contracted.

On the other hand, in the past, home builders demonstrated a remarkable ability to amend their practices rapidly, overcome initial hesitation and respond to market need when presented with the opportunity to make significant profits. Examples are the rapid rise of suburbia and the construction of small homes in the post-Second World War era, the building of vast rental estates in the 1960s and 1970s and most recently, the mushroom of the condominium market in many Canadian cities. With this in mind, one can assume that newly emerging market trends will foster large-scale demand for new types of dwellings and intrigue the industry to act relatively fast. Builders, for example, will be unable to ignore the wave of baby boomers looking for smaller and more adaptable units, or renovations to existing homes to make them adaptable to users with reduced mobility.

In the coming decades, the Canadian housing market and the home-building industry are expected to face several constraints. Most notable is the need to respond to environmental challenges, changing demographics and new economic realities. If past events are any indication of future action, the industry, once again, will show resilience. The challenge, however, lies in predicting the degree of innovation that builders will be willing to embrace.

Avi Friedman is a professor and co-founder of the Affordable Homes Program at the McGill School of Architecture in Montreal, Canada. He is an author of 16 books and the principal of Avi Friendman Consultants Inc.