Over the past century or so, the housing problem has ceased to be one of poor living conditions and instead become one of affordability. This is a bit of a simplification, though.

Over the past century or so, the housing problem has ceased to be one of poor living conditions and instead become one of affordability. This is a bit of a simplification, though.

Affordability has always been an issue for many Canadian households, especially renters. In 1900, two-thirds of city-dwellers rented and many single people roomed in lodging houses or boarded in private homes. Then again, even today some people’s homes fail basic standards of health and comfort. This is most obviously true for Indigenous Canadians in urban areas and especially on reserves, which are still a national disgrace.

But today, affordability, not housing conditions, is the biggest issue for most Canadians, above all in urban areas. We have never paid so much, or such a high proportion of our incomes for housing, and the services that usually go with it.

Technology

Critics have blamed the building industry for this situation, noting a low rate of innovation. Most dwellings are still assembled on site, so construction crews are moving from place to place, coping with the vagaries of the weather – while other commodities, from cars to clothing and food, are now mass-produced, often at the lowest possible cost. However, over the past couple of centuries, builders have actually invented or adopted a wide range of materials, tools and techniques transforming the building process.

The biggest change in the 19th century was the introduction of balloon framing, which is the use of two-by-fours and nails. It requires less wood and less skill than the previous methods used by Indigenous communities or European colonizers. Invented in the American Midwest, balloon framing initially had limited impact in Ontario and Quebec. But it greatly eased urban and rural settlement on the Prairies and in the West in the early 20th century. In the postwar era, balloon framing became the Canadian suburban norm.

Other methods that we now take for granted arrived more recently. From the 1920s, the introduction of wallboard replaced numerous skilled plasterers with fewer, semi-skilled tradespeople. Mid-century prefabricated roof trusses and door and window assemblies replaced and de-skilled carpentry. Both innovations reduced costs. In the 1940s, power tools made carpenters, roofers and other trades far more efficient. They have also enabled many amateurs to do their own home improvements.

Here is our current paradox. We have never built homes more efficiently. Relative to incomes, the costs of producing and shipping building materials, and fashioning and assembling them, have never been lower. So why do finished homes cost so much?

Standards

An obvious answer is that our standards have risen. On the average, our homes are bigger and better. There are two reasons for this. The first is rising expectations – we have redefined preferences as needs. We take it for granted that homes will have basic appliances such as vacuums and stoves – we now expect all household members to have their own bedroom (and even their own bathroom). Today, at 2000 square feet, the average single-family home is more than twice as large as it was in the late 1940s.

We now expect not only piped water and sewers and the electrical services that drive appliances, but also cable, Wi-Fi and air conditioning. In 1900, middle-class families could take the first set of services for granted, but even in urban areas a working class family might not have enjoyed any of them. It makes sense that as homes have become larger, offering more privacy and comfort, we should pay more.

For a persistent, significant minority of households, finding the money to pay the rent is a regular source of anxiety, and everyone who is trying to buy a home for the first time is daunted by the price.”

Another explanation for rising standards is that, for a variety of reasons, our governments have required them. Fires were one of the great scourges of 19th century cities, and municipalities responded by imposing tougher regulations that prohibited some building materials while mandating others. From the 1940s, these and other requirements were incorporated into a national building code.

Another urban scourge was disease. Health regulations were introduced to govern sanitation, ventilation and overcrowding. In 1912, at the instigation of its Medical Officer of Health, the City of Toronto enacted a by-law that required all property owners to install connections to the city’s water and sewer systems. More recently, local and national standards have been introduced, governing energy efficiency and insulation. Each of these initiatives has raised the price of housing, whether because of the costs of the requirements themselves or those of enforcement. Red tape itself has a price. For that reason, many regulations have provoked resistance, from residents as well as from builders. For the most part, however, Canadians have recognized that such requirements have saved lives and served the public good.

Land

Whether chosen or imposed, rising standards are only part of the story, and not the most important. The oldest cliché about real estate is that value is determined by location. The price of a dwelling, or what it rents for, reflects above all the value of the land on which it sits. Anyone who has entered – or tried to enter – the housing market in Vancouver or Toronto in recent years is acutely aware of this fact.

Apart from local variations, the fact is that the cost of urban land and housing has always been more than its rural counterpart. Inevitably, as a rising proportion of Canadians have come to live in urban areas, a growing majority must pay urban prices. In 1850, 13 percent of Canadians lived in urban areas. By 1901, this proportion had risen to 35 percent, by 1950 to 63 percent and by 1970, the upward curve began to level off at 77 percent. This trend made it very likely that, over the long run, a rising percentage of Canadians would have to pay more for their housing and face the problem of affordability.

The situation is not quite that simple, of course. People have moved to cities, and immigrants to Canada have stayed there, because they have perceived an economic opportunity. With better jobs and higher incomes, they could afford the higher price of city living, just as Vancouverites can afford to pay more for housing because, on the average, they earn more than residents of Hamilton or Saint John. But the story does not end there. Indeed, it is only a footnote in the story of urban land.

The key issue is that the price of urban land, and therefore housing, will always rise relative to incomes as long as those incomes are increasing more rapidly than the cost of other necessities, notably food, clothing and transportation. The reason is simple. In urban Canada, housing has been provided mostly by the private sector, with the strong support of the federal government since the 1930s. Today, more than 90 percent of all dwellings are privately owned, whether by homeowners or by landlords.

The price of that housing is determined through a bidding process, with buyers and renters paying what they can. Competition pushes prices up so that households end up paying close to the limit of what they can afford. When the price of other necessities falls, what people can and do pay for housing tends to rise.

Here, then, is another paradox. As our whole system of production has become more efficient, the relative cost of land and therefore housing has risen.

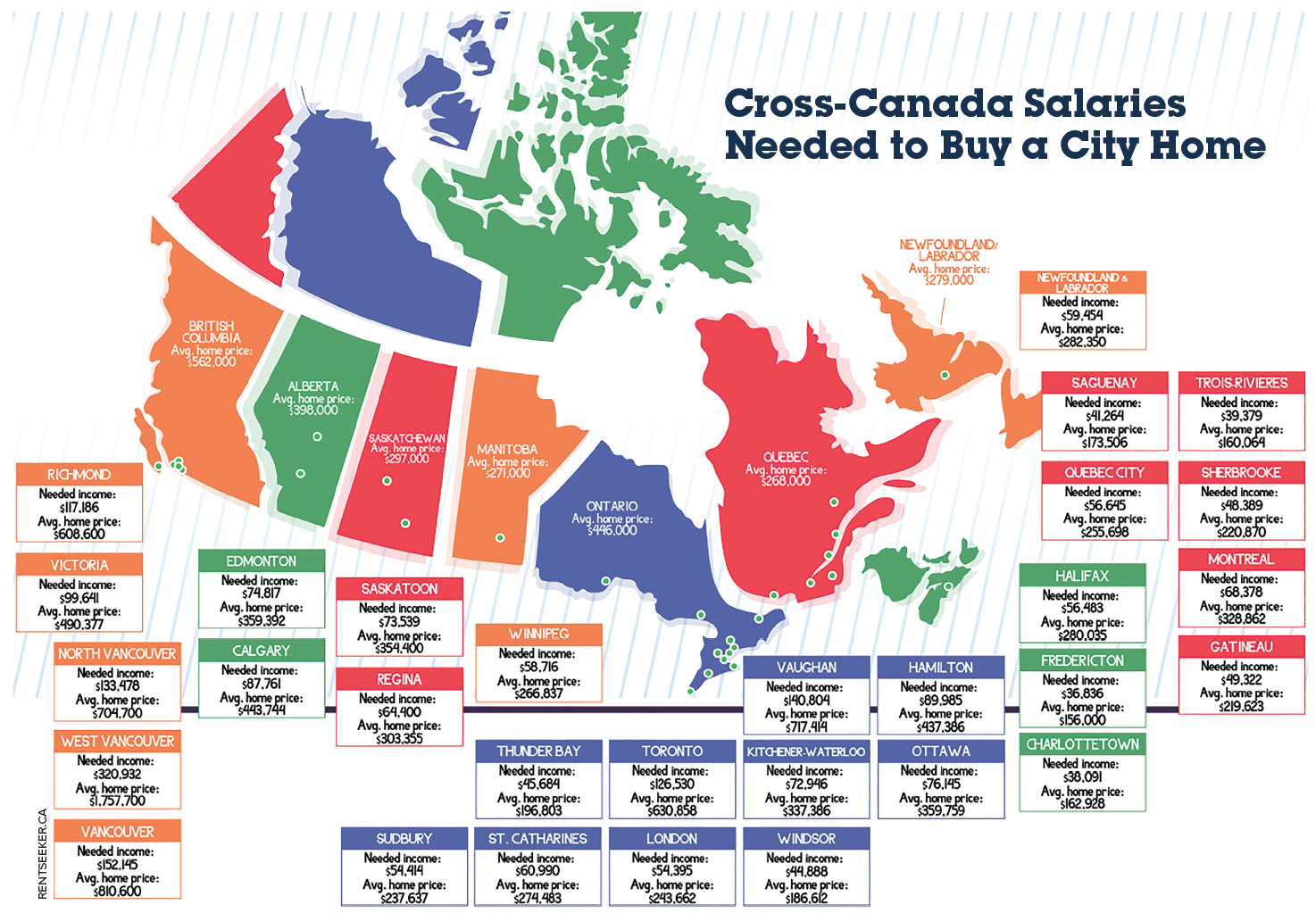

In April 2016, when this rentseeker infomap was updated, the highest average home price was $1,757,700 and the needed income to mortgage this would be $320,932. On the other hand the lowest average home price in Canada was $156,000 and the needed income was $36,836. Buyer beware – there are other personal factors that individuals must consider, but by these numbers, the capital of New Brunswick is the most accessible to home buyer. Source: Rentseeker.ca

Implications

At first glance, it may seem odd that rising productivity has been associated with a steady increase in the absolute and relative cost of housing, so that many Canadians face serious problems of affordability and even homelessness. But, like many paradoxes, this one reflects complex historical patterns of causation.

This complexity is, or should be, a warning to those who seek to address current housing issues. The normal approach has been to offer subsidies, whether directly or through tax expenditures. Although the public debate on this topic tends to focus on social housing, more than 93 percent of such subsidies go to homeowners. In whatever form, however, they have only temporary impacts. In the short run they help some people but, to the extent that they enable beneficiaries to pay more for their homes or apartments, they simply push prices up. In the long run, nobody benefits.

Another solution, tried in the past, is to remove at least some housing from the market system through the governmental purchase or direct provision of public housing. There are several difficulties with this, not least being the inequity of helping some people but not others – unless, that is, the program is carried through on a very large scale. The greatest challenge, however, is that it can only have a substantial effect on housing costs if the cost of land is reduced – that is, subsidized.

The political question is who provides this subsidy? Municipalities can rarely afford to do so. Instead, in recent years there has been talk of requiring developers to play a role by mixing some affordable housing in with market-priced units, perhaps by negotiating deals whereby the developers are allowed to build at higher densities. Such “inclusionary housing” can have a useful impact in strong markets where developers’ profit margins are large.

But some observers argue that the most effective long-term solution is to tax away all or part of the increase in land value that is associated with urban development. Currently, even though rising land values reflect the investments of local governments in infrastructure, and of numerous neighbouring landowners, owners of property reap the full benefit of that increase. If the increase in value is the result of collective action, shouldn’t it accrue to the public, instead of to private landowners?

This point of view was first argued in a consistent fashion at the end of the 19th century by Henry George, who favoured a single tax on land. Today, in North America, a more moderate version is promoted by the Lincoln Institute for Land Policy in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The logic is impeccable, and limited versions have been attempted in various places. However, for Canada’s foreseeable future, the politics of taking such a step look to be intractable. The problem of affordability is here to stay unless citizens start to demand more direct and immediate action.

Richard Harris teaches urban geography at McMaster University. He has written about the history of housing, neighbourhoods and suburbs, especially in the 20th century.