Housing represents the single largest store of wealth among Canadian individuals and families, and is the largest expense in most household budgets. Housing epitomizes the concept of “use value” where the worth of something comes from how it is used, and not its resale price. Historically, as land was passed down through generations within families, the home symbolized family and social identities.

Housing represents the single largest store of wealth among Canadian individuals and families, and is the largest expense in most household budgets. Housing epitomizes the concept of “use value” where the worth of something comes from how it is used, and not its resale price. Historically, as land was passed down through generations within families, the home symbolized family and social identities. In some countries and communities, a significant proportion of contemporary housing remains within the same families for hundreds of years.

Over time, and particularly within Western economies in the post Second World War era, housing evolved into a commodity that is often, and sometimes primarily, traded for its “exchange value” – where the worth of something comes from its market price, as a commodity providing returns. When this happens, housing is increasingly seen as a “pure financial asset.” The securitization of mortgages, which allows for claims to future housing-based payments to be packaged and sold to other investors, caused housing to become part of global financial investment activities, like stocks and other tradable securities. The converse of this development is the emergence of new credit instruments (such as lines of credit) and rising household indebtedness.

Canadian housing evolution

Mortgage lending in Canada

Canada’s housing system includes both market (for-profit housing development) and non-market elements (cooperatives and government-assisted housing), and both owner-occupied and rental sectors. Founded on principles of private property ownership, Canadian land markets have been active since even before the Dominion land surveys of the 1870s, and urban land and housing markets have experienced booms and busts since at least the 1850s. Until the 1940s, most mortgages were either financed privately or by insurance companies, often in the form of five or 10-year interest-only loans fully payable upon maturity. The federal government explicitly sought to entice Canada’s private banks into mortgage lending for new housing, originally through joint (government-and-bank) loans, first authorized in 1935, and later through mortgage insurance offered by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), starting in 1954. Such mortgage insurance protects the lender rather than the borrower in case of default, thus making the issuance of mortgages that conform to federal criteria almost risk-free for lenders. This kind of mortgage insurance – extended to resale housing in the 1970s, and then to private mortgage insurers in the 1990s – continues to this day as a key motivation for private lenders to issue mortgages for private residential investment.

Growing ownership

Historically, between one third and two thirds of households in Canadian census metropolitan areas have rented their housing. Until the 1940s, most rental housing was provided by the private sector in market or quasi-market forms, including early private cooperatives. The relative availability and quality of rental housing deteriorated during the Great Depression and the Second World War. This spurred all levels of Canadian government to promote various non-market housing programs, from the early wartime housing program (1941-1949), the public housing program (most concentrated between 1964 and 1974), to non-profit and non-equity cooperatives funded through government loans or interest-rate subsidies (more prevalent from 1973 through 1993).

Going forward, the federal government should move to limit – or eliminate outright – the spread of predatory loans.

In 1993, under a restructuring of programs, the federal government announced that it would download most of its responsibilities for delivery of such non-market forms of housing to the provinces. Some provinces likewise responded by downloading their responsibilities to municipalities that had few resources for maintaining, let alone expanding, the units. Very little new purpose-built rental housing – market or non-market – was constructed after this time, forcing many would-be renters into the owner-occupied sector.

Mortgage securitization

In an attempt to stimulate private mortgage issuance without incurring new liabilities, the federal government brought in the first mortgage securitization scheme in 1987. This allowed lenders to package mortgages conforming to the National Housing Act (NHA) into mortgage-backed securities, which could then be sold on the secondary mortgage market. Low investor interest over the 1990s led the federal government to change the program in 2001, setting up a special purpose trust (the Canada Housing Trust) to issue bonds to investors and use the proceeds to purchase NHA mortgage-backed securities directly from lenders.

This allowed private lenders to package newly issued mortgages into NHA mortgage-backed securities and sell them to Canada Housing Trust, thus getting the mortgages off their books right away. This system meant not only that banks shouldered even less lender-risk since they could easily off-load the mortgages, but also that they could continue to issue new conforming mortgages almost without limit. The banks steadily increased the amount they loaned in relation to borrower’s income during the 2000s, which meant mortgage credit became consistently easier to access. This boost to demand, coupled with the lack of new rental housing, caused a rise in the number of properties traded on real estate markets. More lending also produced a systematic rise in housing prices. The increase in the value of real estate assets turned housing into one of Canada’s star investment opportunities during the 2000s, and encouraged a culture of speculating on the exchange (or resale) value of real estate.

Global financial crisis

When the global financial crisis hit in late 2008, Canadians were already highly leveraged, mostly from taking on large mortgages to purchase ever-more costly private housing. Large Canadian lenders were also in potential trouble, having high leverage ratios that could have made them insolvent if the value of the assets they held on their books, including the value of US-based investments, were to fall. The federal government responded by reducing interest rates, and with a program to have the CMHC purchase NHA mortgage-backed securities directly from Canadian lenders, spurring the latter to continue making mortgage loans. This was called the Insured Mortgage Purchase Program.

These responses were very successful in encouraging the banks to lend, because they effectively subsidized mortgage lending and removed virtually all remaining risk from lenders. The abundance of credit created by these programs boosted demand for housing. It also attracted additional international investment. This is because the Canada Mortgage Bonds (issued by the Canada Housing Trust) had higher interest rates than regular government bonds and were seen as riskless to investors, since their principal and interest are fully guaranteed by the federal government.

This, however, has placed the federal government in an awkward position. Now the solvency of the CMHC and in turn the federal budget deficit became not only highly exposed to the real estate market, but dependent on maintaining housing values. The federal government thus had to walk a fine line of limiting its liabilities while maintaining the flow of investment into the housing market.

Otherwise, it would risk shouldering the losses that might befall private investors, whom the government backed in the event of a housing correction, as well as the costs related to the recession that would follow.

The federal government responded by tightening the criteria under which mortgages conform to CMHC insurance limits, promoting the covered bonds program as a substitute for NHA mortgage-backed securities and an incremental shift of mortgage insurance capacity to private-sector insurers away from the CMHC. However this move led to new contradictions, including the rise of subprime lenders who offer mortgages at much higher interest rates and outside the regular regulatory framework, leading to potentially greater instability and vulnerability for those homebuyers who use such lenders.

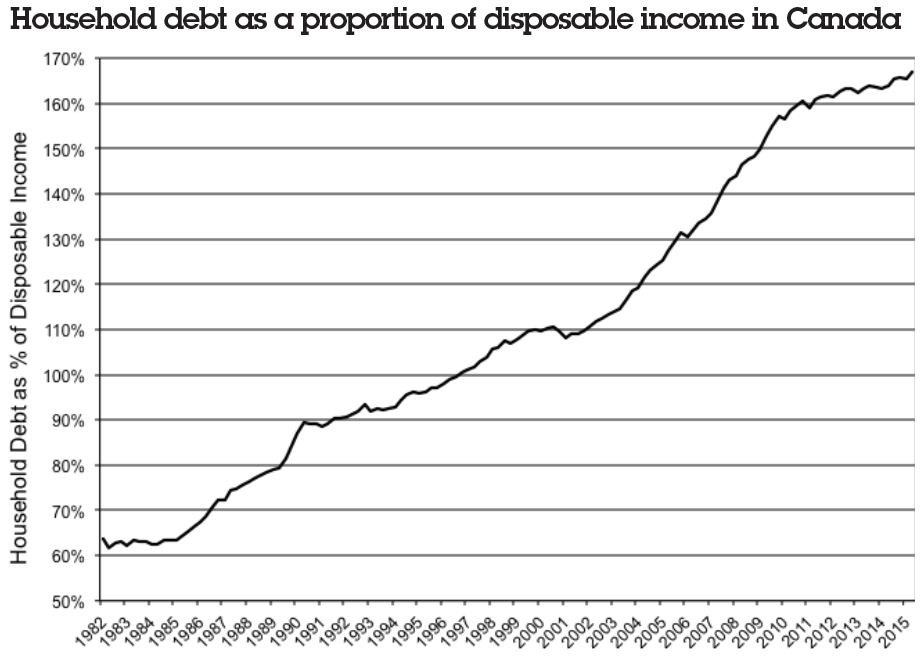

While Canadian income has increased, rising mortgage liabilities have also increased the average debt-to-disposable income ratio, which has more than doubled since 1980.

Source: The data for 1990–2015 comes directly from Statistics Canada’s CANSIM II Table 3780123. The data for 1982–1989 is calculated from CANSIM II Tables 3780051 and 3800019.

New urban inequality

Growing debt

Rising indebtedness is producing a new urban inequality characterized by a widening generational gap in wealth, increasing class polarization and an increasingly vulnerable immigrant population. This is all part of what I call the new “debtscape” – which takes into account the geography of debt and wealth, as well as the terrain of government policies, financial practices, cultures of investment, the financialization of corporate and business practices (i.e., the increasing importance of financial investments and instruments in generating profits over traditional business practices in production, sales or resource extraction). The debtscape also includes patterns of interest and other debt payments and flows at multiple spatial scales such as: the global scale of financial firms, banking, securities trading and investment; the national scale of regulations around lending and securities trading; the regional and municipal scale of infrastructure development, housing and real estate markets, automobile sales and financing, and regional economies of innovation; and the neighbourhood scale of uneven house price appreciation, foreclosures and commuting flows.

In large part due to rising mortgage liabilities, the average debt-to-disposable income ratio among Canadians more than doubled between the early 1980s and early 2015 (see chart). A recent analysis by Alexander and Jacobson (“Mortgaged to the Hilt,” 2015) found that the proportion of Canadian households with debts greater than five times their annual disposable income increased from 3.4 percent in 1999 to 10.8 percent in 2012, although the caps inherent in the dataset used by the authors of this study mean that this is a conservative estimate of the actual increases.

Already in advance of the global financial crisis Meh et al. (“Real Effects of Price Stability,” 2009) noted that the bottom wealth quintile was in a negative equity position due to high debt loads, and this worsened further for these people between 2005 and 2012. However, the top three wealth quintiles saw their net worth rise according to Statistics Canada. Lafrance and LaRochelle-Cote (“The Evolution of Wealth,” 2012) and Alexander and Jacobson (2015) show that debt-to-income and debt-to-asset ratios worsened at a faster rate for poorer households and younger mortgaged households. Meanwhile, aging baby boomers and retirees have been able to cash out of their housing positions and/or downsize to smaller and cheaper housing at historically unprecedented price levels. Together, this situation represents an effective transfer of wealth from younger and poorer households to older property-owning generations.

Geography & demography of debt

Such developments have produced an uneven “debtscape” across Canadian communities. High debt loads have disproportionate impacts on more vulnerable and more marginalized people. Analysis of the 2009 Financial Capability Survey conducted by Hurst (“Debt and Family Type,” 2011) for Statistics Canada shows single-parent families’ debt-to-income ratios are 57 percent higher than the average. They are 2.7 times more likely to pay 40 percent or more of their income on debt service than couple families with children.

Compared to their incomes, immigrants to Canada have debt levels 43 percent higher than the native-born, and are 2.5 times more likely to be putting over 40 percent of their income to debt service, even after controlling for income and family type. Those under 35 years of age had much higher debt levels (as a percentage of their income) than older households, aged 50 to 64.

Tellingly, after controlling for other socio-demographic variables, Hurst found that households with incomes less than $50,000/year have debt levels 162 percent higher than households in the next category ($50-79,999), and 253 percent higher than households earning $120,000 and over. And after controlling for other socio-demographic variables, the lowest income category of households (<$50,000/year) are over 23 times more likely to be paying 40 percent or more of their income on debt service than are households in the top income category.

This debtscape is also characterized by the increasing financial vulnerability of particular places. Metropolitan areas in British Columbia in particular have very high ratios of household debt to household disposable income, followed by Calgary and a number of metropolitan areas in Southern Ontario, notably those within the Greater Toronto Area. Debt loads in general are higher in the suburbs of most census metropolitan areas. However, among those with mortgages, it is households within pre-war inner city areas – particularly those areas that are gentrifying – that reveal the highest mortgage-debt ratios.

Perhaps the best suggestion for helping households expunge their debts is a “modern-day debt jubilee.”

At the local scale, richer neighbourhoods have lower levels of debt across most Canadian metropolitan regions. For every increase of $10,000 in average annual household income in a census tract, debt as a proportion of disposable income declines by 5.6 percent. So a community with an average household income of $50,000/year has a debt-to-income ratio that is 56 percent higher than a neighbourhood with an average household income of $150,000.

Meanwhile, neighbourhoods containing more people aged 65 and over reveal less indebtedness. Debt levels are lower by 25.4 percentage points for every 10 point increase in the population share of seniors. A neighbourhood where seniors (age 65+) make up only 10 percent of the population thus has a debt-to-income ratio that is 50.8 percent higher than a neighbourhood where seniors make up 30 percent of the population.

Overall, this suggests a transfer of financial risk away from places where wealthy households and seniors live, and towards places containing younger and lower-income new households. It is the latter that are thus most exposed in the face of recessions, rising interest rates, or housing-market corrections.

How do we move forward?

By 2015 the Canadian housing system had become laden with risk, increasingly unaffordable and with far fewer options given the erosion of non-market forms of housing. There is a clear need for programs offering different models of social housing provision, so that low-income households are not compelled to take on debt to avail themselves of housing in the owner-occupied sector. The current model is bad not only for individual low-income households. Large shares of the population experiencing growing indebtedness have far-reaching potential consequences for highly indebted communities, cities and the entire national economy (and even beyond – the global financial crisis is proof of that).

However, the horse of high indebtedness has already left the barn, and Canadian housing values have reached bubble territory. This places Canadian households on the whole in a very vulnerable financial position, as it also does the federal government, which has insured over $500 billion in outstanding mortgage debt. Both are susceptible to any decline in house prices, as well as to growing unemployment and rising interest rates.

Too late?

While the federal government moved to tighten mortgage lending criteria in 2012, it was largely too late. The mortgage securitization scheme Canada begun in 1987, “perfected” in 2001, and ramped into overdrive with the Insured Mortgage Purchase Program in 2008, was working too well to stimulate borrowing and lending.

The federal government should have designed the Canada Mortgage Bonds program differently and imposed caps on the mortgage insurance CMHC offers to lenders (to limit incentives for over-lending). It should never have allowed zero-down-payment mortgages with 40-year amortizations (as the Conservative federal government allowed between 2006 and late 2008), and should never have selected the Insured Mortgage Purchase Program as a vehicle for rescuing the economy during the financial crisis.

But these mistakes are now in the past. While further protective measures are definitely welcome, it’s important to note that tightening the mortgage-lending criteria in 2012 may actually have encouraged less regulated and more subprime forms of lending.

The hand already dealt

Going forward, the federal government should move to limit – or eliminate outright – the spread of predatory loans, subprime and other high-interest loans. This applies to both those loans collateralized by housing and other consumer loans (including those related to automobile purchases, payday lending, etc.). The government should compel lenders to replace these with loans issued on standard, non-predatory terms. Tighter regulation of maximum interest rates and lending terms is necessary in the name of fairness, and will help those who are suffering from job loss and predatory loans. But at this point, none of this is likely to ease the macroeconomic risks from a housing market correction.

Even more important will be the need to deal with the already high debt overhang facing Canadian households, which along with rising interest rates or economic decline could result in many Canadians losing their homes and their jobs. High debt loads make deleveraging and deflation a real possibility going forward. The solution is to implement policies that raise incomes relative to debt levels, and that will help expunge debt.

The federal government, by virtue of its control over Canadian monetary and fiscal policy, is in the best position to address this situation. One way to raise incomes could involve putting Canadians to work building new urban infrastructure that would use fewer resources and be more sustainable in the long term. I am thinking here of public transit and active transportation options (there is likely already enough housing).

These initiatives would provide real gains to wealth, health, environmental sustainability and quality of life going forward. Furthermore, if they were funded through monetized government bond issues, then nominal wages would increase relative to nominal debts, making past debts easier to pay over time. These ideas have been tested before, and governments of all stripes have used infrastructure spending to stimulate economic growth. Indeed, a significant proportion of the bridges, tunnels, highways, city halls and other infrastructure built in the United States were built during the Great Depression for exactly this reason.

Meanwhile, perhaps the best suggestion for helping households expunge their debts directly are the various proposals, by economists such as Steve Keen, as well as others, for a “modern-day debt jubilee.” Federal payments could be directed electronically to each household’s financial accounts such that if they held high-interest debt, payment would go toward that first, followed by lower-interest debt (mortgages). If the household did not have any debt, then such deposits would be directed into their savings account. This scheme would directly pay down debt, keeping deflation at bay, while also not punishing savers, tenants and otherwise more prudent households. If each household were provided with the same flat amount, this would also accomplish a degree of income redistribution, disproportionately benefitting lower-income households and places, and thus helping to address class inequality.

Thinking the unconventional

While some might not yet be ready for these proposals, if Canadian housing markets significantly deteriorate, and unemployment and debt deflation become entrenched, such “unconventional” solutions might be necessary. These policy options would be more effective in the face of deflation than the untested idea of negative central-bank interest rates, which Bank of Canada Governor Steven Poloz has already floated publicly. There is potential for Prime Minister Trudeau’s planned infrastructure investments, if designed carefully, to help raise wages and create new jobs. However, they will likely need to be accompanied by direct measures to expunge debt, such as a modern debt jubilee, and tighter regulation on predatory lending.

Alan Walks is a professor of urban planning and geography at the University of Toronto. He is the editor of The Urban Political Economy and Ecology of Automobility: Driving Cities, Driving Inequality, Driving Politics (Routledge 2015), and co-editor of The Political Ecology of the Metropolis (ICPR 2013).