FROM THE END OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR UNTIL 1989, Europe was severed by a strip of barbed wire, minefields, watchdogs and spring guns. Nations on the Western side, mostly NATO members, were politically, economically and militarily divided from Warsaw Pact signatories in the East. Attempts to traverse the barrier were perilous, and most Europeans kept their distance.

FROM THE END OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR UNTIL 1989, Europe was severed by a strip of barbed wire, minefields, watchdogs and spring guns. Nations on the Western side, mostly NATO members, were politically, economically and militarily divided from Warsaw Pact signatories in the East. Attempts to traverse the barrier were perilous, and most Europeans kept their distance.

By excluding humans, the border zone unwittingly welcomed nature. While some areas and their resident wildlife (especially in Eastern Europe) were devastated by strip mining, Soviet tank maneuvers and motion-sensing machine guns, ecosystems ranging from Arctic tundra to peat bogs to alpine meadows flourished along the Iron Curtain during its decades-long respite from disturbance. Environmentalists on both sides noted this increase in biodiversity, but little could be done to officially protect it amidst the tense political climate of the Cold War.

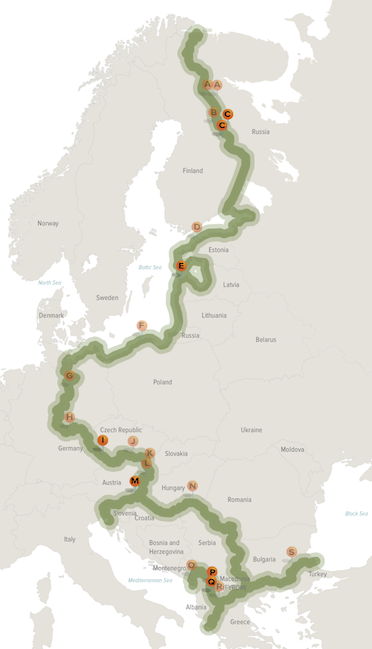

Order your copy of the Greenbelts issue for stories

about all 17 points along the Green Belt.

Following the Iron Curtain’s collapse in 1989, conservation initiatives started springing up along its former path. Cross-border cooperation led to the establishment of protected areas, which have since been increased and expanded to form vast networks. In 2002, the German conservation organization, BUND, proposed the creation of a pan-European greenbelt spanning the entire length of the former Iron Curtain. A series of conferences attended by delegates of the 24 former border countries have brought this idea to life during the last decade.

The 12,500-km European Green Belt now extends from the Barents Sea in the north to the Black Sea in the south, and includes four organizational regions: Fennoscandian, Baltic, Central European and Balkan. Although its width ebbs and flows, the greenbelt covers the same distance as a path from Vancouver to North Sydney, Nova Scotia, and back again.

“This ecological corridor is an outstanding memorial landscape of European relevancy with a great potential for transboundary cooperation, sustainable regional development and the merging of Europe,” explains Liana Geidezis, regional coordinator of Green Belt Central Europe. “It is a unique chance that last century’s zone of death shall become a lifeline across Europe. Nature knows no boundaries.”

The points of interest profiled on the following pages are just a fraction of the European Green Belt’s mark on the landscape – a snapshot of the species, habitats, complexities and collaborations that are driving its development. Learn more at euronatur.org.

Fennoscandian Green Belt

C. Finnish-Russian Friendship Nature Reserve

Access to the Finnish-Russian border zone was prohibited for a period of 60 years during the Soviet era. Forests along this 1,250-km strip were thus left to flourish and emerged as a dark green strip in satellite photos of the region as early as 1970. Cooperative efforts to conserve natural areas on both sides of the border began later that decade. The two countries signed a cooperation agreement in the 1970s, and another related to environmental protection in 1985. The latter sparked the establishment of a Finnish-Russian Working Group on Nature Conservation, whose efforts to protect species and natural areas continue to this day.

In 1990, the cross-boundary Friendship Nature Reserve was established to conserve the habitat of wild forest reindeer and to promote cooperative research comparing the responses of similar natural environments to different management strategies on either side of the border. The reserve is the founding park of the Fennoscandian Green Belt, shared between Kuhmo, Finland, and Kostamus, Russia. This spirit of cooperation now extends to Norway as well: the Pasvik Inari Trilateral Park, completed in 2003, spans the Barents region of Finland, Russia and Norway.

Baltic Green Belt

E. Latvian Coast

The Iron Curtain also limited access to the beaches and forests along the Latvian coast to local residents and military personnel. Many artifacts of the Soviet regime can still be found in this region, presenting an opportunity to develop military tourist attractions. Yet some bunkers, tanks and watchtowers are being left to degrade, and the number of living citizens with in-depth knowledge of their significance is dwindling.

One shining example of historical revitalization that could be emulated is the Radio Astronomy Tower in Irbene. This was a secret Soviet outpost that intercepted NATO communications during the Cold War, using a still-intact 32-metre satellite dish. The tower and surrounding structures were abandoned when Latvia regained independence in 1991, and then reinvented as a space research facility and tourist destination. Researcher Juris Žagars explains the on-site atmosphere: “You could shoot a horror movie called Frankenstein and the KGB here without having to spend a single lat [a unit of Latvian currency] for the sets.”

The Radio Astronomy Tower in Irbene, Latvia. Photo: Konstantin Lazorkin.

Central European Green Belt

I. Šumava National Park, Czech Republic

While the European Green Belt strives to foster cooperation, conflict is sometimes unavoidable. Decisions by government and park authorities have come under fire from environmental organizations, which insist Šumava National Park’s primary role as a nature reserve is being undermined.

One point of contention has been the clear-cutting of forest stands infested with bark beetles. While government authorities have claimed this is necessary to protect healthy trees, conservation groups argue that the damage done by bark beetles is a natural process in the forest’s lifecycle and that the logging is economically motivated. The controversy came to a head during a peaceful blockade in 2011. Despite public outcry, logging continued in 2012.

A new law that adjusts the sizes of zones within the park to correspond with different levels of protection has also sparked debate. The Czech government has described the law as a compromise that balances stakeholder interests. But some conservationists disagree, criticizing the decision to allow construction of a chair lift in a zone designated to receive the most stringent protection. Disputes over the management of Šumava will likely continue.

M. Murtum Nature Observation Tower, near Gosdorf, Austria

The Murturm Nature Observation Tower. Photo © TAUSP.

A small village in southern Austria offers a great example of how some communities are welcoming the increased visibility that comes with their involvement in a pan-European greenbelt. In 2009, Gosdorf mayor Anton Vukan and conservationist Johannes Gepp spearheaded the construction of an observation tower, capitalizing on an opportunity to draw more tourists and enhance interaction with the surrounding landscape.

The Murturm Nature Observation Tower ambles 27 metres above ground level to reveal a stunning vista of riparian woodlands along the Mur River. Conceived by architects Klaus Loenhart and Christoph Mayr, the tower’s acclaimed double-helix design provides visitors with a panoramic view during their entire ascent, as well as a different route back down. The tower’s shape also references the delicate spiral of a DNA molecule and pays tribute to an iconic staircase in a nearby 15th century castle. As though imitating the branches of neighbouring trees, the top of the tower sways slightly in the wind.

Tourist traffic to the Mur Nature Reserve has increased since the tower opened in 2010. The attraction is also popular with locals, who take pride in the region’s natural beauty and helped fund the construction project.

Balkan Green Belt

P. Mavrovo National Park, Macedonia

The 6th pan-European Conference on the European Green Belt was held in June 2012, drawing about 100 participants from 21 countries. While the conference recognized past achievements, it prioritized getting governments to protect the future of Europe’s natural heritage, still under threat in some areas.

Attendees were especially concerned about plans to build two hydroelectric plants in Mavrovo National Park. Funded by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the World Bank, the Boskov Most and Lukovo Pole projects would involve the construction of a 33.8-metre-high dam, access roads, an artificial lake and a channel system. This infrastructure would impact large areas of the park, including its most ecologically sensitive zone.

Critics cite a dubious environmental assessment, possible contravention of international conservation commitments and potential threats to the endangered Balkan lynx population as reasons to scrap the projects. Addressing Macedonia’s Environment Minister at the conference last June, BUND representative Kai Frobel recommended the country turn to photovoltaic technologies instead.

Boskov Most is currently on hold while the EBRD conducts an internal review. Progress on Lukovo Pole, however, continues to move forward.

Q. Jablanica-Shebenik National Park, Albania

The Balkan lynx (Lynx lynx martinoi) is a subspecies of Eurasian lynx that is endemic to Macedonia, Albania, Kosovo and Montenegro. The mere 40 to 60 individuals that remain must cope with poachers, habitat loss and other threats, and their reproductively isolated and likely genetically distinct population is classified as critically endangered.

The Balkan lynx (Lynx lynx martinoi) is a subspecies of Eurasian lynx that is endemic to Macedonia, Albania, Kosovo and Montenegro. The mere 40 to 60 individuals that remain must cope with poachers, habitat loss and other threats, and their reproductively isolated and likely genetically distinct population is classified as critically endangered.

Learn more and see rare images of the endangered Balkan lynx in our web exclusive, Balkan Beauties.

To read about the other locations on the map, order a copy of the Greenbelts issue today! Then check out our interview with Liana Geidezis from Green Belt Central Europe in the Greenbelts podcast.

The sections on Suomussalmi, Finland; Paldiski, Estonia; Bratislava, Slovakia; and Röszke, Hungary, were written by Alexandra Varela, a recent masters’ graduate from uWaterloo who specializes in East German history. Maps are by Anezka Gocova, a uWaterloo Planning grad and A\J’s graphics intern extraordinaire. Map GIS data courtesy of BUND – Project Office Green.

Ellen Jakubowski is a former A\J editorial intern with a BSc in Biology from the University of Guelph and a science communication diploma from Laurentian University. She works as an interpreter at the Cambridge Butterfly Conservatory and blogs about animals in The Wild Side.