To watch Anthropocene is to be saddened and overwhelmed.

Overwhelmed by our remaking of the Earth’s surface through extractive industries; by the destruction of living creatures on land and at sea; and by the injury inflicted on humans, especially the poor, as they participate in these processes.

Earlier societies harnessed and harmed nature as well. But for Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky, “What is different today is the speed and scale of human taking,” he says, “and that the Earth has never experienced this kind of cumulative impact.”

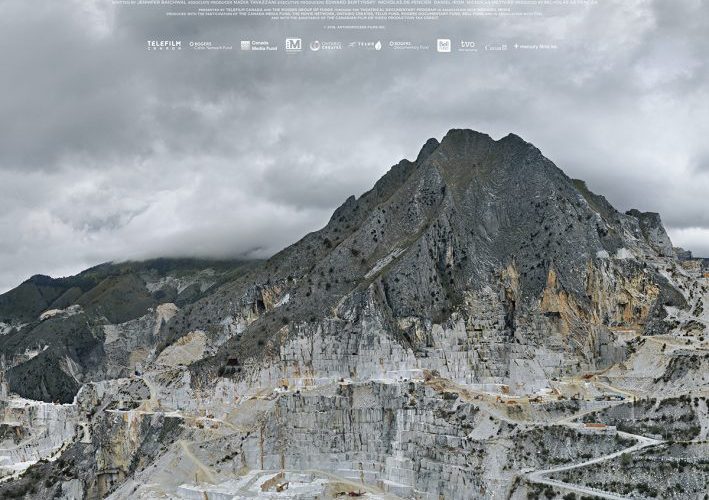

Joined by Jennifer Baichwal and Nicholas de Pencier, Burtynsky travelled to 20 countries, including Italy, Russia, Nigeria and Kenya to document changes well underway. Spoken word is at a minimum. Rather, what speaks here is machinery and landscape.

We witness construction workers remove massive chunks of marble from a quarry in Carrara. The operation is set to a soundtrack of Italian opera and displays that art form’s intensity and drama. When the house-sized block is finally pried from the hillside and snapped off, we feel theatrical climax. Earth’s dismantling is a performance on a grand scale.

We visit Lagos, a metropolis of 20 million (imagine half the Canadian population in one city) and see children carrying heavy sacks of sawdust. They are barefoot labourers in the timber industry. We watch as loggers in British Columbia turn diverse, complex, enigmatic forests into monocultures of broken sticks.

We tour Germany’s largest open-pit mine and glimpse the world’s biggest excavating machine, a vehicle that seems as large as a mid-rise condominium.

What effect might this film have on audiences? Could it foster political engagement, a desire to protect nature? These are open questions.

We ride a train through the world’s longest rail tunnel, Switzerland’s Gotthard Base, which took 17 years to build and runs beneath the Alps for 57 kilometres. Imagine the force required to blast through that length of mountain. Even advancing a few metres would be a titanic project.

The film includes a major section on climate change. We’re taken to Venice, where we witness the flooding of Piazza San Marco. A man carries a friend on his back through the water-logged streets. I appreciate that the filmmakers show extreme weather in a wealthy nation. This is a disaster the rich cannot avoid.

Moments of Beauty

But Anthropocene has moments of beauty. We’re taken underwater and view the brilliant neon reds and whites of fish. We watch a magnificent sea turtle slowly paddling through a reef. When it stops, it seems to take a moment to reflect. Yes, the reefs are mortally threatened by acidification, yet their richness and grandeur are evident nevertheless. Even the squalid landfill in Nairobi, with its filth and plastic, hosts gorgeous long-legged birds.

What effect might this film have on audiences? Could it foster political engagement, a desire to protect nature? Can it lead to lifestyle changes, such as flying less, or motivate viewers to join advocacy campaigns? These are open questions.

The film’s wide theatrical release across Canada is a hopeful sign. It’s not showing in obscure festivals or art houses. In Toronto it’s playing mainstream cinemas across the city. It may be able to reach (and spark discussion among) people who don’t normally take part in this debate.

George Marshall, the guru of climate outreach, has said campaigners need to engage folks not at all like themselves, respect their values and speak to their concerns. Based on this formula, Anthropocene is well-executed environmental communication.

It’s a formidable piece of art with the power to attract affluent viewers who enjoy documentaries but have limited interest in ecological matters. They may come for the cinematography and leave with the knowledge that rising sea levels threaten their favourite holiday destination. This might prove sufficient reason to learn about global warming and, over time, work for its mitigation.

Reviewer Information

Gideon Forman is a long time peace and environmental activist.