Is it easier for us to embrace “belonging” if we know who doesn’t belong? Can we respect someone – let them belong – even if we don’t particularly like them?

Is it easier for us to embrace “belonging” if we know who doesn’t belong? Can we respect someone – let them belong – even if we don’t particularly like them?

Enigmas such as these run through an interview with Adrienne Clarkson, but so does her optimism. Canada’s former Governor General is passionate about her message that the state of belonging isn’t a finite concept – we’re not going to run out of it if we build a country where all of us feel we truly belong. And practicing inclusion is not about liking someone.

“Society isn’t built upon people liking each other,” Clarkson says. “It is built around the fact that everybody is a human being and deserves the same treatment and respect that you do. They have the right to live just as you do, and therefore life and society has to be organized around them just as it is around you.”

At the time of last spring’s interview, Clarkson was preparing for her lecture “Belonging: Diversity, Community Capacity and Contribution” at the University of Waterloo. Clarkson, a humanitarian, award-winning journalist, and scholar, has a deep understanding of her subject. For one thing, she knows what it is like to develop a sense of belonging as an immigrant – her family came to Canada from Hong Kong in 1942 when she was just three years old.

In fact, that’s part of her recognition of the surface layer of belonging – the numerous cultural touchstones, stereotypes if you will, that we think make us truly Canadian. These include Timbits, “beaver tails”, hockey, wearing toques, apologizing for everything, good beer, and, of course, that we are an open, welcoming society. Clarkson believes these touchstones “play an integral role in how we feel about our role in our communities and our country.”

They can be a foundation on which we connect. For new immigrants, embracing these cultural touchstones is part of a transition into a new social home.

Society isn’t built upon people liking each other. It is built around the fact that everybody is a human being and deserves the same treatment and respect that you do.”

But Clarkson is also intrigued that we frequently build our national identity by defining what we are not – specifically how we are not like the United States. This concept has so grafted itself onto who we are that we are unable to see the cultural forest for the trees. We seem to feel more secure in our own belonging when someone else does not belong – as if there are only a few spaces at the table and we want to ensure that we have one.

Clarkson speaks frequently of “the other” and “othering,” a process that happens when we engage in behaviour that seeks to exclude. This involves us, as individuals and as a social collective, attributing negative traits (such as violent, untrustworthy, etc.) to a specific group of people; anything that highlights how their differences are too great for us ever to get along.

We start to see them as a threat to our society and the very ideals we claim to value. It comes down to saying: “We don’t want you; you don’t belong,” Clarkson says. When someone is “othered,” they become “less than” – less than a person and if someone isn’t considered a person, it is easier to excuse and justify their exclusion and marginalization from society.

Clarkson laments that “we are always being faced with people who have no idea whatsoever of what the ‘other’ is – and don’t care and couldn’t make any effort whatsoever to see what the ‘other’ is like.”

And that needs to be corrected. Our membership in Canada is “dependent on us reaching out and embracing the other,” she says.

She also points out that there is an element of “knowing” people that subtly underwrites the idea of belonging, that somehow you should know all the people in your community and that it is the knowing that means they belong.

“But you can’t be actively involved with everybody,” she points out. “There are simply too many people in world, let alone in our own communities for us to have a genuine relationship with each of them. There is always going to be people who you don’t know.” As individuals we have a spectrum of how many people you can be actively involved with – there are roughly 110 people on the outer edge of any one person’s engagement circle. Considering people are a spectrum, that’s anywhere from 30 to 150 people you’re both willing and able to “put the work in for,” she comments.

And Clarkson understands that it’s unreasonable to expect that you’ll have an effective relationship with everyone in that circle. “We don’t have the human capacity to remember all of the details of more than that.” If the idea of belonging is dependent on a having an effective relationship with everyone, than that model is flawed and deeply unachievable.

For Clarkson, the secret to belonging is straightforward: “To be able to look at one another and actually see one another.”

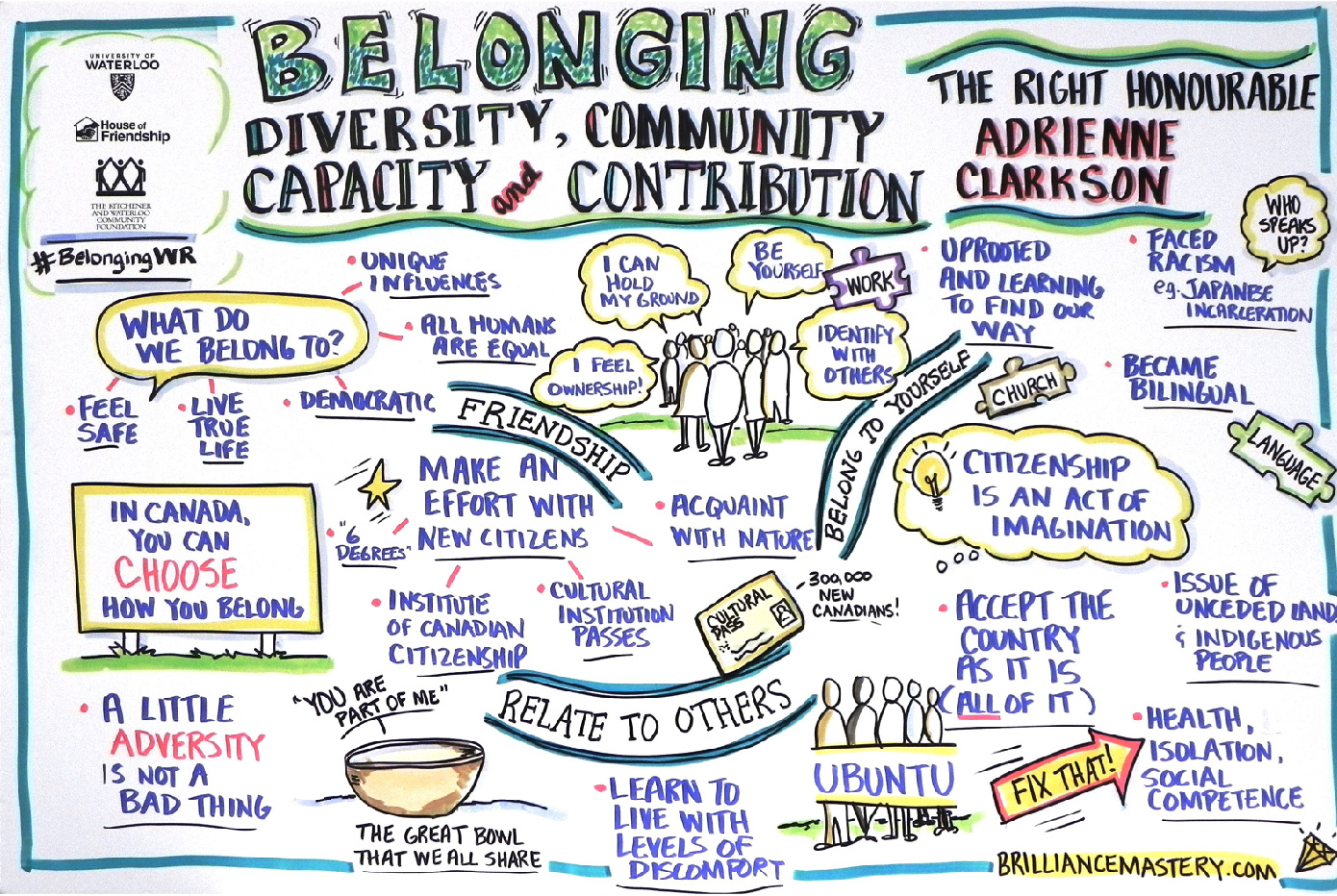

This illustration created during Clarkson’s talk at the University of Waterloo summarises her most important concepts.

Illustrated by Carolyn Ellis, courtesy of The KWCF.

Call to action

Clarkson highlighted two significant ways in which we can make an impact, one a societal act and one an individual act.

She argues passionately about the importance of public institutions (such as schools, community centres, swimming pools, arenas, libraries): “Our institutions help craft people and communities into the type of people we want to be. They play an active role in building who and what we are, so they become fundamental in this way. We need to respect those institutions and steer them with kindness, for they shape the future.”

It is in these spaces that we learn to reach out across social divides and see each other as unique individualized people. We start to build relationships, and build commitments to each other and to our macro and micro communities. We then take these building blocks and bring them with us when we enter other spaces.

But if we don’t act as stewards for our institutions, they can become the very things we don’t want them to be.

When publicly funded institutions are eradicated, we get a strictly divided society based on class and race. These institutions then set up the strict guidelines for who are the “right” kind of people to mingle with, ensuring that the “right” people know each other and by keeping out any “undesirables.”

Public institutions counteract that. Canada still remains a nation of immigrants and Clarkson believes that “public schools and institutions create a mixture of every type of person in society, every background and that helps create who you are as a human being.” We become citizens through this mixing process.

Clarkson believes we should be happy to know our taxes go to support such fundamentally important work. “Don’t begrudge property taxes and the like because it goes to schooling … to your children, to your grandchildren, to other people’s schooling, which is important because what are we if we’re not part of a society that contributes to the well-being of others.”

The second call to action is of a personal nature, the one where you begin to make the changes in your own life. Clarkson asks that we each be “present in the willingness to act and to speak by inserting yourself into the world.” That when we see injustice, acts of racism, homophobia, misogyny, ableism, etc., we have the courage to stand up and speak.

“It takes a lot of courage” to do that, Clarkson says, but “it is very important to speak out. That’s what democracy really means; it’s speaking out, it’s taking your place in the world, it means leaving your own private self and entering the public world and of course it means taking a risk when you do that.”

But that risk will be worth it. If being a welcoming society is a key element to who we are as a nation, than we ought to be working hard to make sure it’s true. Each of us has a role to play, as individuals and in our communities.

As Clarkson reminds us, “Canada is a project to which we are all contributing to, and that we have a role in the world to play.”

Teghan Barton is a self-proclaimed Crackerjack Canadianist, having earned both an BA and MA in Canadian Studies where her focus is on issues of belonging, nationalism, and cultural policy. She is very passionate about social justice and working towards creating a safe and healthy future for the planet.