Richelle Martin isn’t your typical activist. The third-year student in Philosophy and Interdisciplinary Leadership at the University of New Brunswick has always been interested in environmental issues but had no experience organizing or leading any kind of public campaign. This all changed a few months ago, rather unexpectedly.

Richelle Martin isn’t your typical activist. The third-year student in Philosophy and Interdisciplinary Leadership at the University of New Brunswick has always been interested in environmental issues but had no experience organizing or leading any kind of public campaign. This all changed a few months ago, rather unexpectedly.

When Martin and two other UNB classmates began researching ideas for an assignment in their leadership and community projects class, they learned about a burgeoning fossil fuel divestment campaign that was making headway south of the border and slowly gaining steam in Canada. For almost a year now, students on campuses across the US have been challenging their university and college administrators to take concrete action to confront the climate crisis by removing fossil fuel companies from their endowment portfolios.

For their assignment, Martin and fellow students Kayley Reed and Christina Wilson founded Fossil Free UNB. Although their class ended last spring, their campaign to persuade the university to divest from fossil fuels has only just begun.

Climate change campaigners around the world have long struggled to find meaningful ways for individuals to contribute to solving what is a complex, seemingly intractable problem. One reason divestment is galvanizing students is that it provides a practical way to participate in collective action that could help reduce the political power of the wealthiest industry on the planet. “Climate change is going to affect young people more than anybody else,” says Martin, “so we need to take responsibility for making changes. This campaign appealed to me because it targets students to take leading roles.”

Over the past few months, Fossil Free UNB has collected hundreds of student signatures, seen a near-unanimous resolution in favour of divestment passed by the student union, and met with both the president of the university and the UNB Investments Committee. Although the committee was not convinced of the merits of divestment, Martin and her friends remain undeterred. They are ramping up the pressure this fall by creating a formal organization on campus, enlisting more student support and tapping into the growing network of students across Canada who are engaged in similar efforts at their own schools.

Divestment campaigns have been used with varying degrees of success by a number of social movements over the years. The idea is to convince individuals or an organization to sell shares in an unethical company or industry to raise public awareness about its transgressions while hitting the offenders where it hurts – their bottom line.

Whether public pressure to divest from companies doing business in South Africa had any significant role in ending the apartheid regime in the 1980s is a contentious matter. Yet it is almost certain that the campaign helped to reframe the ethical debate and greatly increase knowledge of the injustice of apartheid. The fossil fuel divestment movement believes that, in climate change, humanity is now facing another moral crisis that demands we take sides: if it’s wrong to wreck the climate, it’s wrong to profit from the wreckage.

Inspired by the struggles against apartheid and big tobacco, Bill McKibben’s climate change organization 350.org decided to launch a widespread Fossil Free Divestment campaign following the re-election of Barack Obama in 2012. Aided by a handful of groups such as the Sierra Club and the Energy Action Coalition, the campaign built upon existing coal divestment efforts in the US, first targeting the endowments of postsecondary institutions and then broadening its scope to include municipalities, religious institutions and foundations. Their goal is simple: to “take on the industry,” according to 350.org communications director Jamie Henn. “Students see divestment as a tangible way to make an impact [on climate change] at the local and national levels.”

The campaign has since spread to more than 300 US colleges and universities, but so far only six have committed to pursue divestment – and not one of those has an endowment larger than US$1-billion. (For context: Large research universities like Harvard and Yale have endowments of more than US$30-billion and US$19-billion, respectively – and in early October, Harvard’s President stated it would not divest because its board members did not consider such a move to be “warranted or wise.”) Eighteen cities and municipalities in the US have also signed on, including Seattle, San Francisco, Berkeley and Portland (Oregon), as well as a number of religious institutions. In July, the United Church of Christ became the first national faith communion to do so.

The Fossil Free Canada divestment campaign arrived a little later. The Canadian Youth Climate Coalition currently runs the project, although CYCC director Cameron Fenton says student organizers on campuses are driving it. Nineteen student-led campaigns were underway as of early October, and the CYCC is shooting for 30 by November. No Canadian schools have agreed to divest as of yet, but Fenton says it is still early and, in addition to UNB’s progress, there have been other encouraging developments.

For example, the City of Vancouver announced plans in October to examine how its $800-million in investments aligns with the mission, values and sustainable and ethical considerations outlined in its procurement policy. The pension plan of municipal employees in Vancouver includes investments in fossil fuels, mining and tobacco, and city council has decided to take a formal position on responsible investing. Fenton says this could lead to options for divestment, thereby setting a potentially groundbreaking example for other Canadian cities.

The big uptake has been on campuses. Since fall 2012 the Divest McGill group has succeeded in convincing the three major student unions to support their campaign, gathered more than 1,200 signatures from faculty, students, alumni and staff, and in May it formally presented the case for divestment to a Board of Governors Committee. According to Lily Schwarzbaum, an organizer with Divest McGill, the university has investments in 35 fossil fuel companies, which they estimate represents about five per cent of the total endowment. Ultimately McGill’s Board did not consider the petition because they were unconvinced that the “social injury” of fossil fuel investments had been demonstrated, but Schwarzbaum insists the fight will go on. “The divestment movement is about creating new moral guidelines and empowering a generation of young people to take action to rethink the way we live in our society. Divestment is one piece in a larger goal of climate justice. All of these pieces must come together to change the way climate politics are enacted on our planet.”

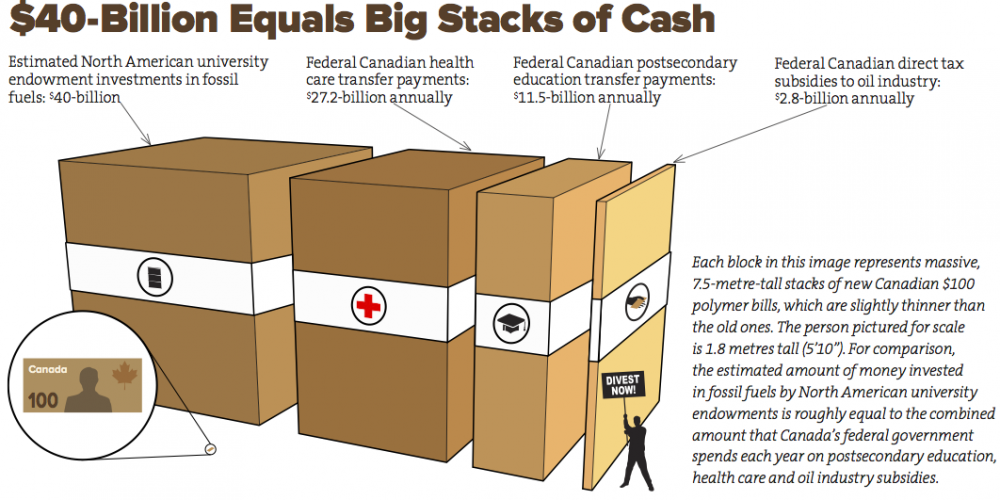

While the details of most university investment portfolios are not made public, 350.org’s Jamie Henn says that total endowments in North America amount to approximately $400-billion, of which roughly 10 per cent are in fossil fuel companies. Investment managers have anecdotally told Cameron Fenton that approximately 30 to 35 per cent of university endowments in Canada are in energy stocks, the majority in fossil fuel companies. As the total endowments of big schools such as McGill and the University of Toronto are more than $1-billion each, we’re talking about hundreds of millions of dollars at stake in Canada – and many billions of dollars in the US.

It is a lot of money, but only a drop in the bucket for companies such as Royal Dutch Shell, which grossed nearly half-a-trillion dollars in 2012 alone. “The dollars are important but the economic impacts extend far beyond this,” says Fenton. “Divestment starts to create uncertainty in the future of fossil fuel stocks and, more importantly, it can take away their social license to operate so that fewer investors will want to pick up their stocks. The goal is to turn big oil into big tobacco – a pariah industry that politicians can’t stand beside in good faith.”

Divestment is not without its detractors. Some observers claim that because oil companies have huge market capitalizations, any divested shares will simply be repurchased by less scrupulous investors, making no real difference in the final analysis while hurting students who depend on the many scholarships and bursaries funded by fossil fuel companies. Some critics say oil companies are simply providing what people want and it would be more effective to focus on reducing consumer demand for oil and ending government subsidies to hugely profitable oil companies.

But campaigners feel that opposing subsidies and blocking pipelines are simply pieces of the climate change mitigation puzzle. “If fossil fuels companies were just providing oil they wouldn’t be spending tens of millions of dollars lobbying to block all climate legislation and get climate deniers elected around the world,” says Henn. “These companies aren’t blameless. For decades they’ve been confusing the public about the science of climate change with well-documented misinformation campaigns and they continue to have a stranglehold on governments.”

The success of fossil fuel divestment depends largely on how it is measured. “No one is thinking we’re going to bankrupt fossil fuel companies,” says Fenton, “but what we can do is bankrupt their reputations and take away their political power.”

Fossil Free Canada is currently on a coast-to-coast Tar Sands Reality Check Tour to help promote divestment and push school boards to divest. “What success looks like to me is what we’re already seeing,” says Fenton. “Something that started with students on campuses has led to fossil fuel companies being genuinely afraid of this campaign. What makes me so confident is just working with these students to see how committed they are to making this happen.”

To launch a personal divestment campaign, Go Fossil Free highlights Green Century Balanced Fund, Portfolio 21 and the Shelton Green Alpha Fund as the only broad-based, completely fossil-free mutual funds. Leading US-based environmental news website Grist also published a useful piece in early October, titled “How to divest from fossil fuels, no matter the size of your piggy bank.”

Mark Brooks is a journalist, broadcaster and environmental educator. Follow him on Twitter: @earthgaugeCA.