IN 1906, the New York City Police Department dispatched mounted officers onto Wall Street to break up mobs of investors trying to buy Cobalt, Ontario silver mine stocks. Simultaneously, thousands across North America descended upon the burgeoning camp cut into the remote northern Ontario wilderness to stake additional claims or seek their fortunes in the mines.

IN 1906, the New York City Police Department dispatched mounted officers onto Wall Street to break up mobs of investors trying to buy Cobalt, Ontario silver mine stocks. Simultaneously, thousands across North America descended upon the burgeoning camp cut into the remote northern Ontario wilderness to stake additional claims or seek their fortunes in the mines.

The Grand Trunk Railway billed Cobalt as “the World’s Greatest Silver Mining Camp” and quickly built rail lines to bring in those desiring quick riches – and some did get very rich. The same lines shipped out 10,000 tonnes of silver prior to the start of the First World War. By the 1920s, however, most Cobalt mines were closed except for a brief resurgence when demand for metals increased during the Second World War.

Today, few Canadians could point to Cobalt’s location on a map, and the small fraction of its former population that remains lives amidst a landscape scarred by arsenic contamination and abandoned head frames, reminders of the region’s reckless heyday. Such booms, busts and associated environmental damage have been a common theme in Canadian mining history. When economically viable ore is played out, the mining companies and workers often move on, frequently leaving behind social and economic devastation for dependent communities, plus vast areas of waste rock, tailings and contaminated water – a catastrophic legacy to be inherited by subsequent generations.

Yet the excitement of a rich and easily exploitable mineral resource that fuelled the Cobalt silver camp in the early 1900s is just as evident today as Canadian mining giants develop resources at home and abroad to feed our near-insatiable demand for raw materials. Globally, mining remains a significant economic driver, contributing substantially to the economic growth of many developing and developed countries despite its substantial social and ecological liabilities. Canada, a resource-based economy, is somewhat dependent on its diverse mining sectors, which in 2012 contributed $52.6-billion in mineral exports (or about 20 per cent of total exports), accounting for 3.9 per cent of the national GDP (using the broadest definition of the sector to include smelting, refining and primary manufacturing). Canada also employs 418,000 workers in mining and mineral processing in over 1,200 establishments across the country.

All current mining operations, in Canada and around the world, involve a range of negative environmental and social impacts on local communities.

Western Canadian mining has focused on copper, molybdenum, gold, nickel and aluminum, while the Prairie provinces have traditionally been world leaders in potash and uranium, as well as gold, copper, nickel and zinc. Northern Ontario and Quebec have long and storied histories of gold extraction, while nickel, zinc, copper, silver, cobalt and chrysotile asbestos were or remain economically important. For nearly three centuries, mining on Canada’s East Coast was dominated by coal, particularly in the Cape Breton region of Nova Scotia. Although little coal mining occurs at present, zinc, lead, iron, aluminum and gypsum remain substantial mining sectors in the Atlantic Provinces. In the far north, the Yukon gold rush of a century ago is long over, but similar initial excitement was experienced by those participating in the recent diamond boom in the Northwest Territories.

While the economic benefits of mining are tangible, twin concerns surrounding human and environmental health persist. All current mining operations, in Canada and around the world, involve a range of negative environmental and social impacts on local communities. A century ago in Cobalt, the arsenic used to capture silver was discarded without treatment or recovery efforts and has resulted in local water concentrations today that are almost 150 times higher than guidelines for the protection of freshwater aquatic life. While there were no regulatory constraints prohibiting environmental contamination in the early 20th century, mining activities now operate under stricter environmental regulations. Nevertheless, environmental disasters do occur, most recently evidenced by the Mount Polley tailings pond breach of August 2014. Seventeen million cubic metres of slurry were discharged into Polley Lake, Hazeltine Creek and nearby Quesnel Lake in the Fraser River system – one of the biggest environmental disasters in modern Canadian mining history.

Although current Canadian regulations require funds to be set aside during extraction for later remediation (grossly insufficient in many cases, including the Mount Polley incident, with the balance of clean-up costs borne by taxpayers), spills and accidents are frequent and the long-term liability of hundreds of millions of tonnes of toxic mine waste stored in surface facilities is often ultimately assumed by governments. Moreover, some Canadian jurisdictions have been weakening regulatory controls (e.g., the federal Fisheries Act) and enforcement (e.g., BC tailings-facility inspections).

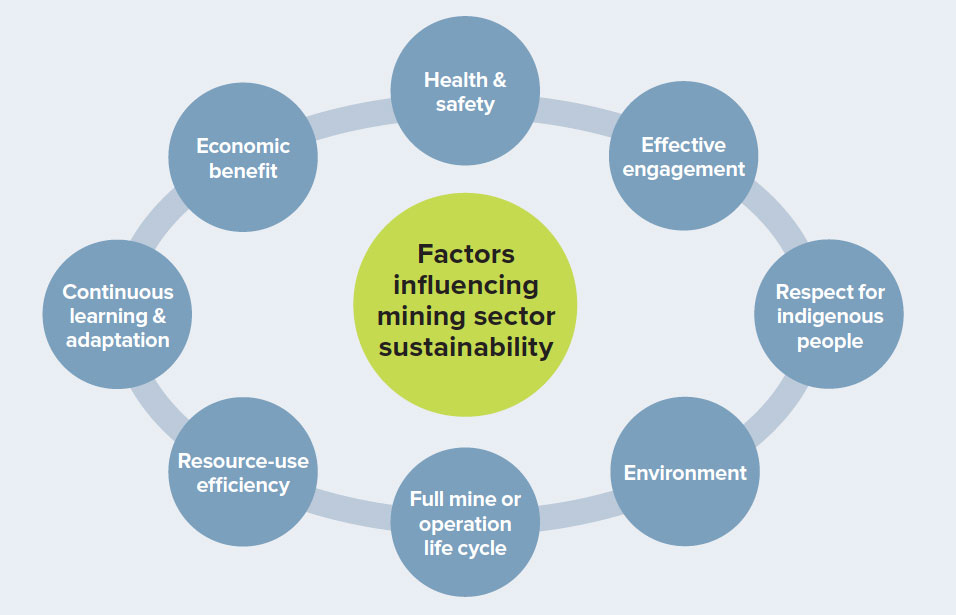

Due to the essentially extractive nature of the industry, every mine depletes a non-renewable ore body of limited life expectancy.

As some of the post-Mount Polley coverage has noted, many of the newer, low-grade, open-pit operations have much larger tailings ponds; with increasing scale come commensurate risks as well as impacts upon potential failure. Due to the capital-intensive nature of modern mining, the boom and bust cycle is less pronounced than in early 20th century Cobalt, but the mining sector is still vulnerable to fluctuations in commodity prices. Current mining projects may be developed over a longer duration to provide a more stable social environment for miners, in some cases over multiple generations. The life limits of mines imposed by the extent of ore body can be extended by permitting only a lower-capacity mill with slower throughput and therefore longer mine life (as was done in the nickel mines of Voisey’s Bay). Vulnerability of mines to global commodity price swings can be softened somewhat by various initiatives, perhaps most simply by refusing to licence economically marginal operations. Social disruption and worker migration, while less pronounced today, remain well-known and important challenges to sustainability for the mining sector.

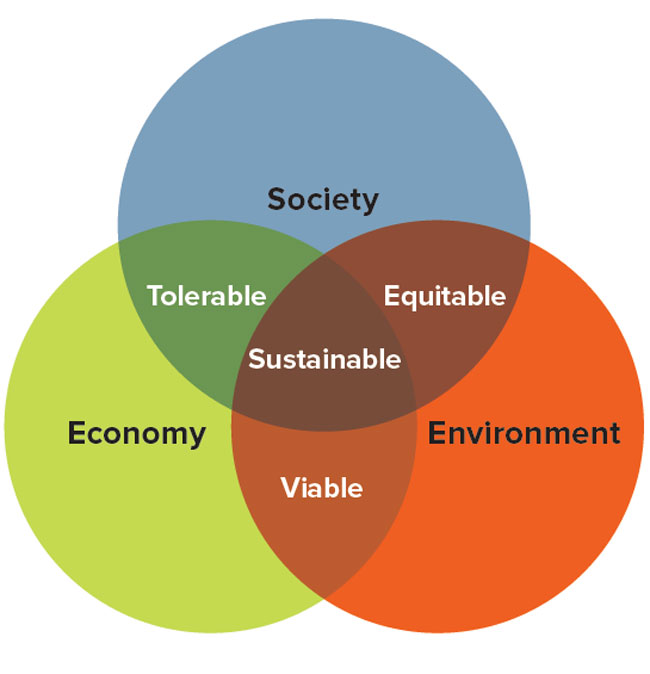

The concern of the general public towards mining activities is changing, however. In fact, growing societal scrutiny of mining practices might mean that resource extraction may simply not proceed outside acceptable and agreed-upon levels of environmental, societal and human health impacts. This change, more than any other factor, has contributed to a shift in the Canadian mining sector toward recognising social licence, and specifically the territorial, treaty and self-government rights of Indigenous Peoples. After all relevant government permits have been issued, the informal social licence afforded by local communities (granted by conditional acceptance or revoked by public protest) of an operation must continually be earned rather than assumed. To meet this challenge, the mining industry must actively incorporate environmental and social as well as economic factors into its business model. In the longer term, mining should be permitted only where and if it provides lasting social and environmental as well as economic gains – that is, where it makes actual progress toward sustainability.

Ken Oakes is a researcher at the Verschuren Centre at Cape Breton University and holds an Industrial Research Chair in Environmental Remediation.

Martin Mkandawire is a chemist and holds an Industrial Research Chair in Mine Water Remediation and Management in the Verschuren Centre for Sustainability in Energy and the Environment at Cape Breton University in Nova Scotia.