Anyone familiar with Margaret Atwood’s writing could be excused for assuming that she is likely not a fan of the Christian perspective. Set in the near future when an ultra-conservative and totalitarian Christian regime has overthrown the United States government, The Handmaid’s Tale tells the story of Offred, one of a class of women kept as “handmaids” for reproductive purposes by the ruling class in face of a declining birthrate.

Anyone familiar with Margaret Atwood’s writing could be excused for assuming that she is likely not a fan of the Christian perspective. Set in the near future when an ultra-conservative and totalitarian Christian regime has overthrown the United States government, The Handmaid’s Tale tells the story of Offred, one of a class of women kept as “handmaids” for reproductive purposes by the ruling class in face of a declining birthrate. The book received, in roughly equal proportions, high praise from literary critics and strident rejection from conservative religious readers.

In terms of Atwood and religion, though, it turns out things are a bit more complicated than they might at first appear. Atwood has in fact on several occasions expressed the belief that we are hard-wired for religion, in which case – as she said in a 2014 interview with Christian TV host Lorna Dueck – we’d better choose a good one if we’re going to make a difference. After all, though an avowed agnostic, she is above all, a storyteller.

So what would a good religion look like? Well, for a start, it would respect the rights and voices of women. But, as has become increasingly clear in Atwood’s public actions and statements over the last 20 years, it would also take environmental issues very seriously. Even 30 years ago in The Handmaid’s Tale, Atwood was referencing environmental problems alongside STDs – one major cause of the falling birthrate in that novel is sterility resulting from pollution. In 1995 Atwood gave up her house in France after President Jacques Chirac resumed nuclear testing. In 2000 she donated a significant portion of her Booker Prize money to environmental groups. In the last 10 years she has used her book tours to promote environmental activism, ensuring that travel on these tours is carbon-neutral, and particularly promoting shade-grown coffee to protect the migratory songbirds of the forest canopy. Since 2006, she and her partner Graeme Gibson, an avid birder, have been joint honorary presidents of the Rare Bird Club within BirdLife International.

click to enlarge

Atwood is ever the realist: she was not brought up on happily-ever-after fairy tales. But what happens when Atwood is faced with not only individual death but species extinction and warnings of global apocalypse? She herself argues she is not entirely pessimistic. Looking at what is perhaps her magnum opus, at least in size, the trilogy of novels MaddAddam published in 2003, 2009 and 2013 are written in apocalyptic mode. In face of real-world fears about an ultimate environmental meltdown, how does this trilogy articulate and critique the ecological sensibilities of our day? Does it offer any hope? And does it, after all, have a place for a “good religion?”

French 20th century philosopher Paul Ricoeur, argued in Freedom and Nature (1968) that fiction is not so much imitative of what is already existing, as descriptive of what might be. In which case dystopian and apocalyptic fiction might be clearing the way for something better in real life. The notion of apocalypse has certainly been used in this way, whether to galvanize or to terrify, or both. The American ecocritic Lawrence Buell wrote in his 1995 book The Environmental Imagination, “Apocalypse is the single most powerful master metaphor that the contemporary environmental imagination has at its disposal.”

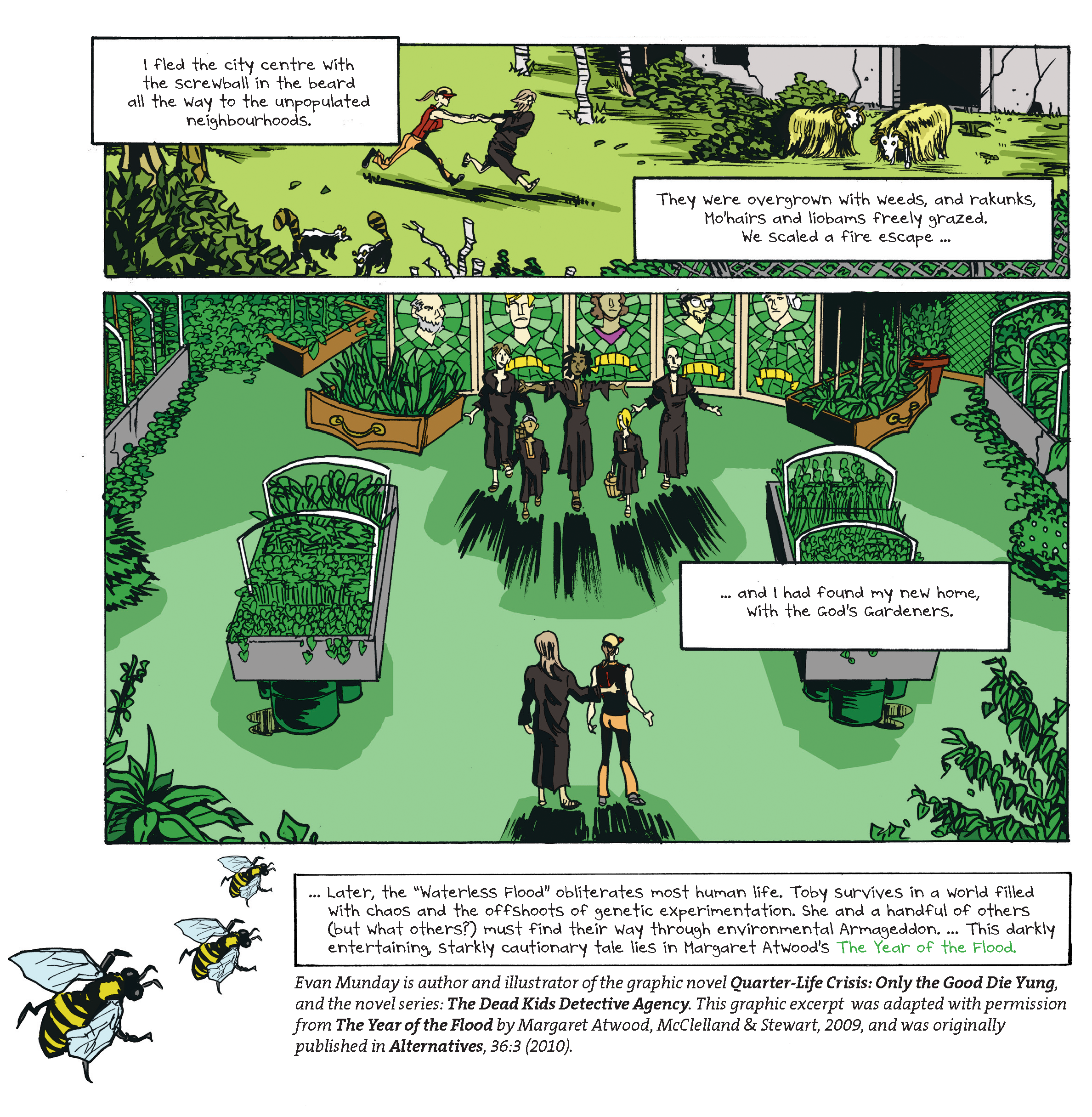

Atwood’s dystopian trilogy of Oryx and Crake (2003), The Year of the Flood (2009) and MaddAddam (2013) centres around a human-made environmental apocalypse, where the final cataclysm is brought about by the brilliant but disaffected scientist, Crake. He lets loose a plague, a “waterless flood,” on the rest of the world reducing almost everyone to literal pulp. The world before the “waterless flood” is already an environmental disaster, where rampant capitalism has treated the Earth as a mere resource and as a result of global warming has suffered floods and droughts of epic proportions.

click to enlarge

Atwood writes on the acknowledgements page of MaddAddam, “Although MaddAddam is a work of fiction, it does not include any technologies or biobeings that do not already exist, are not under construction, or are not possible in theory.” Atwood, whose father and brother were both biologists, writes like a contemporary Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein (1818), speaking

into our current preoccupation with bioengineering, cloning and tissue regeneration. Canadian theologian Anthony Siegrist describes the trilogy as a 21st century extension of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962). In Carson’s book, the opening chapter “A Fable for Tomorrow” shows how humankind is bringing destruction upon itself through its use of agricultural pesticides. Siegrist calls Atwood an “Indigenous ethnographer” who demonstrates the almost irreversible power of technology in the hands of unethical megacorporations.

But that “almost” is vitally important. Because Atwood understands herself to be living within spitting-distance of the situation she describes, and because she is adamant that she is writing realistic speculative fiction and not science fiction, she cannot simply provide a deus ex machina in her fiction to lift humankind out of the mess it’s made. However, she does offer moments of hope. In the trilogy, there is one quite different response to the pre-apocalyptic nightmare: that of the God’s Gardeners, a religious environmentalist group trying to meld faith, science and nature as they raise vegetables and bees on flat roofs in the urban slums. Some readers with past experience of

Atwood see the God’s Gardeners, with their childlike hymns, their vegetarian diet, their recycled crafts and their earnestness, as merely ridiculous, but there is surely more to them than that. Brooks Bouson claims that Atwood “looks to religion – specifically eco-religion – as she seeks evidence of our ethical capacity to find a remedy to humanity’s ills,” and offers the story of the God’s Gardeners about the vital necessity of caring for the oceans, for instance, or the importance of knowing how to forage for edible plants, or the disastrous destruction of the ecosystem of the Amazon River basin.

“It is one of my beliefs that we’re not going to be able to pull this off without an element of faith.”

Atwood has said she tried to include in her litany of the saints of the God’s Gardeners’ calendar “people of all time periods, religions and standpoints –anyone who did what they did because they had an inclusive vision, and no more inclusive is available than Julian of Norwich. She had a vision of the planet itself as held in a giant hand, carefully being held almost like an egg.”

It seems, then, that Atwood is able to draw on what Gerry Canavan has called an “unexpected utopian potency lurking within our contemporary visions of eco-apocalypse.” For her, the pre-apocalyptic landscape turns out to be much worse than the post-apocalyptic. The novels have what Canavan calls a “sense of futurity” at their heart, because they suggest a “reopening of possibility: the assertion of the radical break, the strident insistence that things might yet be otherwise.” Is it possible that the ending of the Christian story, which declares in the last book of the Bible that “the leaves of the tree [of life] shall be for the healing of the nations,” might speak into those concerns? Certainly not if that ending is any kind of extreme version of what some Christians call “the rapture.” It’s also evident that Atwood sees contemporary Christianity as needing to recover from the abusive anthropocentrism of its Enlightenment past, in terms of its perspective on the environment. But she is not alone in seeing signs that a shift in popular Christian understanding may be taking place.

Some interpretations of the Christian “eschaton,” or ending, present a quite different scenario from the common trope of the rapture. In September 2015 Atwood wrote in the National Post that “the ‘stewardship’ movement within the Christian church – recently given a big boost by the Pope – says, in essence, that you can’t love your fellow [human] unless you also love that which sustains [them] in life: our planet’s air/water/earth ecosystem.” Indeed, Pope Francis’ May 2015 encyclical letter Laudato Si’, addressed not just to Catholics but to “every person living on this planet,” affirms that the Earth is to be stewarded as God’s beloved creation. The encyclical has been labelled as historically significant, being the first devoted to environmental issues. Not only that, “it deploys the full weight of magisterial authority behind a passionate call for a far-reaching ecological conversion,” ethicist Jonathan Chaplin has argued.

“Never have we so hurt and mistreated our common home as we have in the last 200 years. Yet we are called to be instruments of God our Father, so that our planet might be what he desired when he created it and correspond with his plan for peace, beauty and fullness,” Pop Francis wrote.

“It is one of my beliefs that

we’re not going to be able to

pull this off without an element of faith.”

It was in February 2014 that Lorna Dueck had Atwood on her TV show Context, alongside a couple by the name of Leah and Markku Kostamo, whom Dueck introduced as “real-life God’s Gardeners.” The Kostamos made quite an impression on Atwood, and she has written about them several times since. In the National Post on August 28 of this year, for instance, she wrote, “faith-imbued environmentalism has at least a chance of working: you save what you love.”

Here is the place of hope, and the place of religion, for Atwood. “It is one of my beliefs that we’re not going to be able to pull this off without an element of faith,” Atwood said speaking about environmental protection at a fundraiser.

What about the faith aspect of the God’s Gardeners? Asked some years ago whether she believes in God the Creator caring for His creation, Atwood replied, perhaps predictably, “If it helps people to understand that they’re part of a larger world than just them, I think that’s great. Religion is a human thing and therefore it can have good and bad aspects like every other human thing we do.

Deborah Bowen is chair of the English Department at Redeemer University College in Acaster, ON. One of her favourite courses on her teaching roster is “Literature and the Environment”.