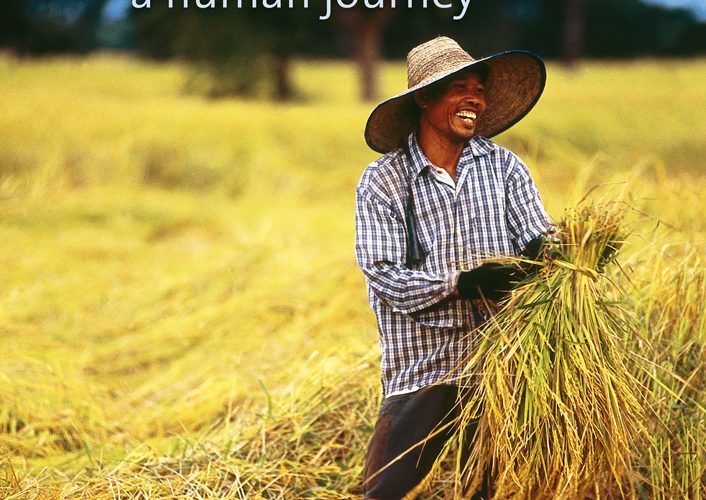

With 350 riveting images, Québec-based photojournalist Éric St.-Pierre takes us into the lives of coffee growers drying beans on jute-covered tables in Ethiopia, flower workers wrapping roses in cardboard boxes in Ecuador, and rice farmers sowing seeds in paddy fields in Thailand. St.-Pierre doesn’t hide the harshness of their lives. Instead he exposes their sun-hardened faces, the bamboo baskets weighing down their backs and the dirt floors of their wooden-pole homes.

With 350 riveting images, Québec-based photojournalist Éric St.-Pierre takes us into the lives of coffee growers drying beans on jute-covered tables in Ethiopia, flower workers wrapping roses in cardboard boxes in Ecuador, and rice farmers sowing seeds in paddy fields in Thailand. St.-Pierre doesn’t hide the harshness of their lives. Instead he exposes their sun-hardened faces, the bamboo baskets weighing down their backs and the dirt floors of their wooden-pole homes.

I concede that before reading this book, “fair trade” conjured a mental image of the Fairtrade International (FlO) logo: a waving figure silhouetted against a green and blue background. When buying a chocolate bar with this logo, I thought warmly of farmers in far-off countries who benefited from my conscientious purchase, but I didn’t picture anything or anyone specific. Fair Trade changed all of that. St.-Pierre’s photography captures the women and men who grow and harvest the cocoa beans for FlO-certified chocolate and other consumer goods with a warmness – a humanness – that made me feel like his subjects’ lives are not so different than mine.

The book’s written content introduces different segments of the fair trade market and provides information about the movement. Focusing first on familiar products like coffee, cocoa and tea, St.-Pierre also sheds light on lesser-known products like shea butter, quinoa and even guarana, which has not yet achieved FlO certification.

St.-Pierre also shares his experiences living in various communities that depend on fair trade. Although his personal observations shape much of the narrative, lengthy quotes give voice to workers, enabling them to describe how fair trade has affected their lives.

Fair Trade has an obvious anthropocentric slant, focusing on how the movement benefits the welfare of the people involved. However, St.-Pierre aptly explains the interconnection between fair trade and environmental sustainability. For instance, he illustrates how sugar farmers at the CoopeAgri plantation in Costa Rica have abandoned traditional field-burning methods, finding financial rewards by protecting 15,000 hectares of virgin forest.

One challenge of this book is its frequent use of the acronyms of the various labelling and certification organizations, co-operatives and unions that work under the fair trade umbrella. I was often flipping back a few pages to remind myself what each one meant. Nonetheless, St.-Pierre and his collaborators do an excellent job of elucidating fair trade’s complicated layers.

St.-Pierre clearly advocates for FlO certification, but doesn’t gloss over the controversial issues that continue to plague the movement. He plunks the reader down in certified tea estates in India where salaried workers still refer to the owner as “king.” He shows us the temporary straw roof of a schoolroom in a Malian village, where cotton farmers await overdue premium payments. On a page dedicated to certification labels, St-Pierre clarifies that fair trade has “no national and international legal framework,” warning the consumer: “This means that anyone can boast of being ‘fair.’”

Still, the overwhelming message of Fair Trade is one of hope. St.-Pierre describes how the fair trade market now produces $5-billion in retail sales, arguing that “the results are undeniable.” He also points out that fair trade is part of a much wider market trend that aspires to consider social justice and environmental responsibility. Even the most vociferous critics would surely acknowledge this truth.

The image that the words “fair trade” conjures in my mind is no longer a vague silhouetted logo. Now I picture one of St.-Pierre’s more poignant images: a laughing, bright-eyed Indian girl in a red and pink dress. But instead of being subjected to child labour on the tea plantation where her parents work, she’s flying through the breeze on a wooden swing, carefree.

Fair Trade: A Human Journey, Éric St.-Pierre, Fredericton: Goose Lane Editions, 2012, 240 pages

This review originally appeared in Lifecycles, Issue 39.1. Subscribe now to get more book reviews in your mailbox!