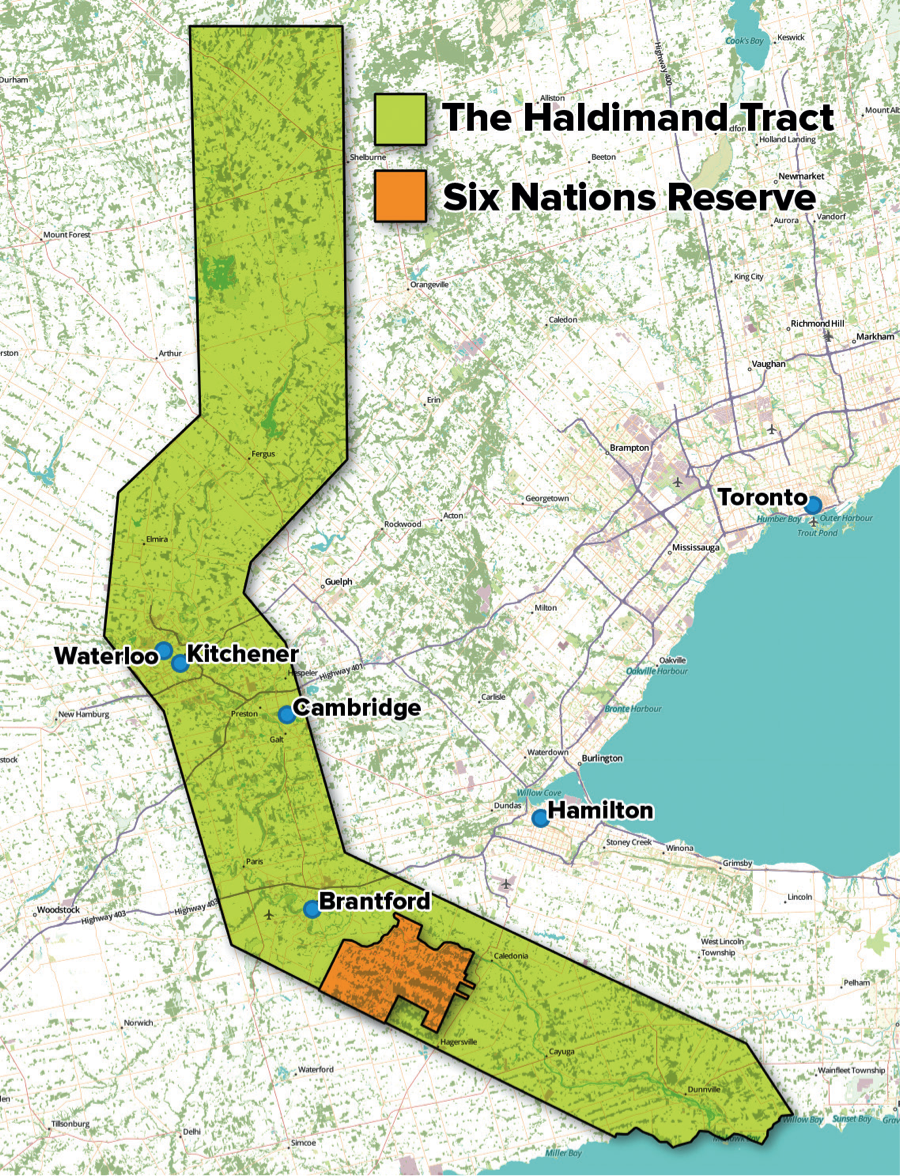

I AM A SETTLER. I’m a white settler, a non-Indigenous occupier of Haudenosaunee, Anishinaabe and Attawandaron lands. Those lands include the Haldimand Tract: a ribbon of territory about 10 kilometres deep on either side of Ontario’s Grand River, which Britain’s Governor-General in Canada granted to the Haudenosaunee people of Six Nations in 1784. These days, where I live is more commonly known as Kitchener and Waterloo.

I AM A SETTLER. I’m a white settler, a non-Indigenous occupier of Haudenosaunee, Anishinaabe and Attawandaron lands. Those lands include the Haldimand Tract: a ribbon of territory about 10 kilometres deep on either side of Ontario’s Grand River, which Britain’s Governor-General in Canada granted to the Haudenosaunee people of Six Nations in 1784. These days, where I live is more commonly known as Kitchener and Waterloo. Both cities are built on land that the Six Nations initially conveyed in trust back to the Crown, on the promise that they would be paid rent for its use for 999 years. The lands were then individually mortgaged, with all funds due to Six Nations. The cities prospered. The money was never paid. I came to the Haldimand Tract to attend school, and decided to stay. For that reason, I am accountable to the history that allows me to live here.

White European racism and the theft of Indigenous lands created the foundations of the benefits I enjoy. Accepting my identity as a “settler” acknowledges openly that I am a contemporary actor in an ongoing history of violence, theft and colonization. It is a way of saying that I want to find a way to correct the injustices I now benefit from.

In 1784, Britain’s Governor-General granted the Haudenosaunee people of Six Nations the land included in the Haldimand Tract. This was to compensate for the land that was taken from Six Nations in upstate New York, and because they fought with the British during the American Revolution. Adapted from Six Nations Lands and Resources. Map data from openstreetmap.org

“Settler” refers to anyone who is not Indigenous living on Indigenous lands. It means not just long-dead ancestors, but any non-Indigenous person who continues to benefit from the colonial seizure of land from its original occupants. This can be hard to accept. Most of us don’t think of ourselves as colonizers or occupiers. We are not all descendants of colonial administrators or occupying soldiers. We have many stories. People leave their place of birth for all sorts of reasons. Most in recent history are not thinking of conquest and colonization. Generally, they are looking for a better life, for prosperity or escape from insecurity. Some, indeed,are descended from people taken by force from their native lands and sold into slavery in the “new world.”

Nonetheless, we need to recognize how colonization has and does still affect us, individually and personally as well as in society. Those of us in particular who believe our politics are “progressive” need to examine our own complicity in upholding and perpetuating colonialism, and whether our ideals truly help or hinder Indigenous movements.

From Idle No More to the Unist’ot’en resistance against oil pipelines in British Columbia, such movements strive to turn around 500 years of history between the continent’s first inhabitants and its relative newcomers. Support for them is essential and important. But solidarity alone does little to change the colonial mentalities and practices that continue into the 21st century.

What do I mean by “colonialism”? I mean the many ways in which settler society – more commonly “mainstream,” “majority” or “Euro- Canadian” society – continues to seize Indigenous lands for settlement and resource extraction. I mean practices that continue to target Indigenous communities with racism and violence, for example, the kidnapping and murder of Indigenous women along the Highway of Tears, or the Saskatoon Police Service dropping Indigenous men on the outskirts of the city in the cold of winter, where many have frozen to death. I mean cultural narratives that continue to cast Indigenous spirituality, knowledge, traditions and ways of life as “primitive,” “less than” or irrelevant. This prioritizes Western perspectives on science or ecology over Indigenous peoples’ knowledge, and prevents their communities from making decisions based on their own perspectives.

Canada was built on unapologetic colonialism. The expansion of European imperial powers like England and France from the 16th well into the 20th century demanded the seizure of Indigenous lands. Their policies openly ordered the coercion, domination and ethnic cleansing of Indigenous communities to make room for newcomers, and allow corporate and location on the Haldimand Tract – still Indigenous land – and contemporary tensions between Six Nations and non-Indigenous peoples, such as those that erupted around Kanonhstaton (“the protected place,” or the Douglas Creek estates in Caledonia, ON) in 2006, are ignored. These omissions are a silent act of colonialism.

This is why it is important to acknowledge and restore the traditional names of territories. When we remember that Toronto is derived from the Haudenosaunee word Tkaronto, meaning “where there are trees in water,” or we replace “Queen Charlotte Islands” with “Haida Gwaii,” we recognize the importance of Indigenous histories, experiences and continuing presence.

But we have similar opportunities as individuals. We can all choose to read and listen to Indigenous voices, in particular those speaking to us from the lands we occupy. The Aboriginal Peoples Television Network and the Mohawk-owned, online Indian Country Today Media Network offer news coverage of Indigenous issues and communities. Reclaim Turtle Island creates grassroots Indigenousled alternative media projects. And Indigenous authors like Coulthard, Leanne Simpson and Joseph Boyden are gaining popularity.

There is much further we can go in deconstructing our colonial present. How might we discuss genetically modified organisms or food security, when we are freed from colonial thinking? Indigenous communities and knowledges have many techniques for meeting daily needs, while still respecting the Earth through native plant cultivation and sustainable hunting practices. Perhaps we could create a better ecological future if we listened more closely to those concerns for the land; if we were more willing to learn from practices that have successfully demonstrated ecological “sustainability” for centuries; and if we gave way more readily to Indigenous rights in law and treaty. Many environmental NGOs have become adept at using Indigenous communities as pressure points to resist destructive developments, but less often join them on the front lines or remain after flashpoint conflicts have faded. Some NGOs do now consult directly, but perhaps they and others might accomplish more if they maintained and deepened relationships with Indigenous communities after a specific campaign.

All of us have the opportunity to join demonstrations of settler support for Indigenous struggles. That could be providing material or financial help for projects like the Unist’ot’en Camp; anti-pipeline resistance in Aamjiwnaang First Nation; or movements against clear-cutting in Grassy Narrows, fracking in Elsipogtog or the tar sands in Fort Chipewyan. It could mean more if we step up physically to participate in marches or other civil action. These efforts are important and useful.

But active solidarity can start closer to home. We can reach out to other settlers where we live and work, and try to expose the colonial privileges and complicities that we all carry. Most of us have opportunities to initiate conversations in the groups we are a part of, in workplace meetings, in classrooms or with the people we are closest to. We can use these moments to introduce the idea that we see ourselves as settlers, and what that means in those settings.

Acknowledging the lands that we are on at the start of public and private events is gradually becoming commonplace, a small contribution of thanks and appreciation to the original peoples as stewards of lands that we can now enjoy the use of. When our institutions, businesses or associations contemplate actions that might bear on Indigenous neighbours, we can argue for fully consulting them. We can attend to Indigenous voices in discussions about public and social issues. We can step back from putting our own voices at the forefront.

As we look for a way to live free of colonial thinking, we can welcome the revival of Indigenous communities, cultures and ways of life. They have cultural knowledge and forms of organization to offer, which might help us find viable alternatives to the environmentally suicidal track the contemporary version of colonialismas-capitalism has put us on. Some alternatives model social and spiritual ways of living in relationship with – rather than dominance of – the land. Others demonstrate participatory, community-based, consensusstyle decision making. Still others create federated communities that preserve local autonomy and displace the need for a centralized state. These alternatives weigh social, environmental, cultural and spiritual points of view on an equal footing with the economic and political. Some knowledge is relevant to science and scholarship: ways of doing research that is accountable and community-led with reference to local practices and protocols.

We are here. Whatever our personal past, how and when we came to this land, we are here now and the colonial legacy of the place has become part of our story. In many ways, shedding that legacy is nothing more – or less – than developing a radical understanding of where “here” is. Understanding what lands we are on, which peoples call them home, and how those lands have been altered. Then we may begin to listen more closely to Indigenous voices and to learn from them a respect for the land that will preserve our own sustenance and life.

We’ve complied a list of books, articles and websites for further reading on indigenous issues from Idle No More to why we need to kill capitalism

Further Reading

Dig deeper into the history and struggles of Indigenous peoples on Turtle Island (North America) with these recommended resources.

Why Does Canada Hate Indigenous Rights?

A\J contributor Ben Powless explains the importance of implementing Free, Prior and Informed Consent in Canada – and why the government is refusing to do so, in spite of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Books

Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back (2011), Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (leannesimpson.ca)

Lighting the Eighth Fire: The Liberation, Resurgence, and Protection of Indigenous Nations (2008), Leanne Betasamosake Simpson and Kiera L. Ladner

This is an Honour Song: Twenty Years Since the Blockades (2010), Leanne Betasamosake Simpson and Kiera L. Ladner

The Winter We Danced: Voices From the Past, the Future, and the Idle No More Movement (2014), The Kino-nda-niimi Collective

Peace, Power, Righteousness: An Indigenous Manifesto (2008), Taiaiake Alfred

Wasáse: Indigenous Pathways of Action and Freedom (2005), Taiaiake Alfred

The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America (2012), Thomas King

Aboriginal Rights Are Not Human Rights: In Defence of Indigenous Struggles (2013), Peter Kulchyski

Undoing Border Imperialism (2013), Harsha Walia

Unsettling Canada: A National Wake-Up Call (2015), Arthur Manuel and Grand Chief Ronald M. Derrickson

We Share Our Matters: Two Centuries of Writing and Resistance at Six Nations of the Grand River(2014), Rick Monture

Settler: Identity and Colonialism in 21st Century Canada (coming October 2015), Emma Battell Lowman and Adam J. Barker

Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition (2014), Glen Sean Coulthard

Articles

For Our Nation to Live, Capitalism Must Die, Rabble.ca, Glen Sean Coulthard

A Global Solution For Six Nations

Decolonizing Together: Moving Beyond a Politics of Solidarity Towards a Practice of Decolonization, Briarpatch, Harsha Walia

Websites

Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, Eric Ritskes (Open Access journal)

Unsettling America: Decolonization in Theory & Practice, a web collection of many resources on decolonization and solidarity

Native Appropriations, Adrienne Keene

Read our exclusive interview with indigenous map maker Aaron Carapella.

Aaron Carapella has been involved in the Native American community since he was a teenager. For 16 years he has been creating unique Tribal maps to accurately represent Native history. You can purchase Carapella’s beautiful maps at tribalnationsmaps.com

Adam Lewis is currently working on a PhD in Environmental Studies at York University on anarchist engagements with Indigenous struggles of resistance.