LOCAL FOOD HAS TAKEN OFF. From coast to coast to coast, the Canadian food landscape is changing. Within local communities, alternatives to entrenched supply-chain strategies are thriving, such as farmers’ markets, restaurants that focus on regional food sources, community supported agriculture (CSA), farm-gate sales and certified organic food production. Increasingly, Canadians are demonstrating that community food systems can combine social and economic well-being with environmentally sustainable practices and healthy food choices.

LOCAL FOOD HAS TAKEN OFF. From coast to coast to coast, the Canadian food landscape is changing. Within local communities, alternatives to entrenched supply-chain strategies are thriving, such as farmers’ markets, restaurants that focus on regional food sources, community supported agriculture (CSA), farm-gate sales and certified organic food production. Increasingly, Canadians are demonstrating that community food systems can combine social and economic well-being with environmentally sustainable practices and healthy food choices.

Consumers eager for local food that is grown in sustainable ways can access a bounty of flavours and regional delicacies from early spring until late fall. Farmers’ markets brim with spinach, lettuces and other greens; boxes heaped with green, yellow and purple beans; shiny heads of cabbage, broccoli and cauliflower; heritage tomatoes in smoky blacks, striped greens, yellows and familiar deep reds; cucumbers for pickling and fresh eating; pungent bunches of cilantro, basil, thyme and sage; and, later, rich varieties of squashes. Lamb, rabbit, grass-fed beef, boar and pork are now available to round out a diet of fresh veggies with rich local meat sources. From this bounty also come prepared foods like wraps, pies and perogies made from regionally ground flour, local eggs and cheese.

And yet, for a nation rich with inland freshwater fisheries and surrounded by the world’s longest coastline, there is a striking absence of fish in Canada’s burgeoning local food movement. We envision a food system in which fresh fish from Canada’s lakes and oceans is readily available alongside the variety of land-based local food. In contrast to the cellophane-wrapped seafood brought in from distant places to fill supermarket freezers, imagine markets with tables of fresh, local fish on ice, ready to be purchased from independent fish harvesters or fishmongers.

Undoubtedly there are important differences between agriculture and fisheries that complicate how we think of food systems. These include the mobile nature of fish compared to captive terrestrial food resources, as well as the common property nature of fish stocks. Nonetheless, as fish is increasingly assigned to private owners in the form of individual transferable quotas that can be bought and sold on the free market, some of the trends that have raised concern among food advocates in agriculture are also being seen on the water. These include more corporate control, centralized decision making, environmental degradation and livelihood challenges.

A lack of access to local fish also has implications for communities that are historically dependent on it. It’s been a staple in the diets of communities across Newfoundland for generations, but there is evidence this is changing. “We mostly got food ourselves,” explains Wanda McGrath [not her real name], who grew up on the west coast of the island in the 1930s. “Wieners came later. When we were growing up here it was the salt fish. Dad grew all our own vegetables. Then came our crowd – [and with them] came the bologna, Kraft Dinner, all that stuff.”

Yet before we can realize a different approach to fisheries that offers communities direct access to local fish and connects consumers with the people and places that are involved in harvesting the fish they eat, there are issues we all need to understand.

Fish has been heralded as an important part of a healthy diet because it provides high-quality protein and essential fatty acids. According to Statistics Canada, in 2009 Canadians ate an average of 7.8 kilograms of fish per person, roughly in line with the Canada Food Guide’s recommendation of two servings (150 grams) per week. Global demand for fish is also rising. A study published by Marine Policy in 2010 reports that most of this demand is supplied by wild marine capture fisheries. Even aquaculture operations rely on wild-capture fisheries for feed.

Employment in fisheries is also crucial to rural livelihoods, both inland and on the coast. Fisheries and Oceans Canada estimated that more than 52,000 people were employed in fish harvesting across Canada in 2008, and a further 27,000 were employed in processing. The vast majority of the harvest is for export markets rather than local subsistence, placing Canada eighth worldwide in terms of total seafood export value. We sell nearly $4-billion in seafood (about 85 per cent of total production) to international markets, with lobster, crab, salmon and shrimp accounting for more than half of Canadian exports.

However, data about trade and consumption tell us little about the nutritional value, quality and origin of the fish Canadians are eating. Likewise, how sustainable are the fisheries that supply Canada? And with demand growing, why are so many fishing communities struggling to survive? Similar concerns about the origins of foods, sustainability of farm practices and the livelihoods of small farmers are at the forefront of the local food movement. Combinations of factors contribute to the absence of local fish, including inadequate labelling and retail access, long supply chains, export-oriented policy and tensions among recreational, subsistence and commercial fisheries.

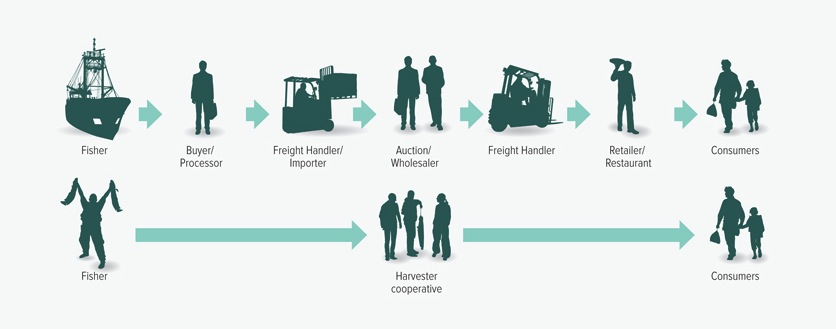

Fish can get lost in the shuffle of the long and complicated industrial food chain, but Community Supported Fisheries and other small-scale options simplify the system and ensure more profit stays with the fishers.

For instance, most packaged food products contain basic information about country of origin and ingredients. But the potential for confusion when buying fish is high because of inadequate retail labelling, lack of traceability and the proliferation of eco-logos and certifications on the packages. As a 2010 article published in Oryx: The International Journal of Conservation pointed out, development of eco-certification standards and definitions of sustainability vary tremendously.

Canada’s seafood and fish labelling standards lag behind many other developed countries because only sparse information is required on our labels, including common species names and country of origin (if imported). Often some of the most important information is not readily available to consumers on fish packaging, including exact species names, whether the product is wild or farmed, the method of catch and the origin of processing versus origin of catch. According to a study published in Food Research International in 2008, up to one in four fish and seafood products in North America is substituted with a lower-grade species or mislabelled. More recently, this profit-motivated practice has become referred to as “fish fraud,” and it can happen anywhere in the supply chain. There is little reason for consumers to be confident they are getting what they pay for.

Another problem is the growing distance between consumers and suppliers, or the typical number of actors involved in getting fish from ocean or lake to plate.

Industrial-scale fishing practices support the large volumes that move through long and complicated supply chains, while centralized purchasing policies often lock out local fish products. The food retail sector is also being consolidated by ever-larger one-stop-shopping supermarkets, which increasingly drive prices and leave fishmongers or independent sellers to become as rare as local butchers. At the same time, the number of small-scale, independent fish harvesters across Canada is declining, meaning that persistent fishmongers are forced to buy from large buyers or wholesalers. In these long supply chains, little of the retail value of the fish reaches the people catching it.

Yet purchasing fish is only one way to access it and only one strategy for bringing it into local food systems. According to a 2010 survey by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, more than three million Canadians participate in recreational (non-commercial) marine and freshwater fisheries. Some participate for sport and pleasure, and many also keep some fish to eat. The history of Canadian waters is riddled with tensions, conflicts and violence between First Nation and settler fisheries, in many cases with Canada’s original fishers (and their primary food source) pitted against wealthy recreational fishers.

But there are also constraints to participating in local fisheries. For example, in Newfoundland and Labrador, the recreational cod fishery is an important summer activity for many residents. Codfish has long been a staple in the Newfoundland diet and many residents catch and put some away for the winter. As described by a June 2013 article in the Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition, declining cod stocks, increasingly short seasons, daily fishing limits and rising fuel costs make participation more challenging for some residents. Further, there are important differences between the colloquial language used to describe the cod fishery for food and the way regulators describe it as recreational. This subtle shift in language reveals profoundly different forms of valuing fish – one as a take-or-leave amenity, the other as a right to fish for food.

An emphasis on commercial fisheries for export can also add to these difficulties. Subsistence fisheries and other country foods are particularly vital to Canada’s coastal and Aboriginal food security, especially in light of recent changes to the northern nutrition subsidy, which continues to make subsidies most available to large retailers and wholesalers for commercial products. This has dramatically increased the cost to transport most foods to the far north, including fresh produce and other perishables. The Assembly of First Nations has committed (over the next five years) to developing and implementing a national fish management strategy as “an integral part of the diet, socio-economic well-being and cultural survival of First Nation communities.”

Certainly there will be challenges to meeting these aims. Most First Nations communities in Ontario are close to freshwater lakes with abundant access to fresh fish. Families and communities that have retained their traditional skills can catch their own consumption. However, fishers with a commercial license have no local distribution system and their catch is often exported.

Newfoundlanders have experienced a similar story of declining access to local seafood over time. “When we were younger we were allowed to catch fish any time,” explains Billy Power [not his real name]. “Fish was something that you kind of didn’t buy. Even if you wanted to get one from somebody [who] was fishing, usually they just give you the fish … it’s not as available as it used to be. You just can’t go out and jig a fish any more. And for the most part, what fish we get, we buy.”

A lack of visibility and access to local fish is also facilitated by policies that rarely treat it as food. For example, in January 2012 Fisheries and Oceans Canada released The Future of Canada’s Commercial Fisheries, which discusses upcoming policy and management changes. The document contains almost no mention of fish as food or even of fisheries as communities, reiterating the primary focus of government agencies on stocks and resources for export production.

Even some food policy documents make this same misstep. For example, Towards a National Food Strategy, released by the Canadian Federation of Agriculture in 2011, makes no mention of fish or other aquatic protein. Similarly, a 2009 survey of local food initiatives by the Canadian Co-operative Association contains no mention of the potential role marine or freshwater fisheries can have in local food systems.

According to a 2013 study by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, recent large-scale trade agreements, including CETA – the proposed free trade agreement between Canada and the European Union – threaten to further encourage the free movement and export of fish and reduce the capacity for local control over fisheries.

Overcoming all of these challenges – insufficient retail access and labelling, long supply chains, export-oriented policies and a history of violence and dispossession between recreational, subsistence and commercial interests – is critical to ensuring that local fish appears in local food systems.

In the context of growing consumer demand for sustainable seafood and the social challenges facing fisheries, local food systems may offer important opportunities for improving access, promoting better practices and supporting small-scale harvesters and communities. For example, a 2010 report released by the Ecology Action Centre in Nova Scotia found that direct marketing can provide strategic benefits, including greater control over pricing and branding for harvesters and better access to high-quality local seafood for customers.

Community based fishery projects are beginning to emerge across North America. Community supported fisheries (CSFs) are adapted from the CSA model, in which a customer signs up for a share of the season’s harvest. In a CSF, an individual, retailer or restaurant buys a share of the upcoming season’s catch, thereby taking on a share of the inherent risks involved as well. This model also reduces the number of actors involved in bringing fish from harvest to consumption and allows harvesters to sell higher up the supply chain. And like CSAs, the approach gives consumers an invaluable opportunity to know where their food is coming from.

Off the Hook is the first CSF in Atlantic Canada. It brings together a co-operative of small-scale harvesters from the Bay of Fundy with customers throughout Nova Scotia. “We have successfully connected customers to local, sustainably harvested seafood,” explains Off the Hook coordinator David Adler. “We are also responding to the growing need for alternative marketing outlets for fish harvesters in an industry increasingly dominated by large, corporate players.”

Customers subscribe at the beginning of the summer season for weekly shares of the co-operative’s catch of haddock and hake. The CSF is designed to provide harvesters with more livelihood control and greater income. It also helps protect harvesters’ safety by allowing them to decide when it is safe to leave the wharf.

While there are only a handful of CSFs in Canada, they offer the promise of a better method. Other types of community initiatives, such as seafood bulk-buying clubs, are also starting to appear. However, these kinds of initiatives cannot achieve a sustained integration of fisheries into local food systems on their own. Policy that supports independent harvesters, fishing livelihoods, community access and clear retail labelling is critical to making Canadian wild fish more visible in local food systems, as well as providing Canada’s citizens with more fish and seafood choices. This transition also requires a shift from the top-down decision making that characterizes much of Canada’s current fisheries management strategy. Effective governance arrangements that involve meaningful community participation will be necessary to allow fisheries to contribute positively to local food systems.

Making local fish more visible and accessible can also begin with your next meal. Learn about what fish is available in your community, who harvests it and how you can get it. And the next time you are perusing the bounty of local vegetables and meats at your market, neighbourhood grocer or restaurant, you might think about asking, “Where’s the fish?”

This article draws on previous work by the authors and others, including:

Bavington, D. 2010. Managed Annihilation: An Unnatural History of the Newfoundland Cod Collapse. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver, BC. pp.186

Lowitt, K. (2013, Forthcoming). Examining fisheries contributions to community food security: Findings from a household seafood consumption survey on the west coast of Newfoundland. Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition.

Murton, J., Bavington, D., and Dokis, C. (Eds.) 2013. Bringing Subsistence Out of the Shadows: Subsistence, Nature and Economy in Historical and Contemporary Perspective. Rural, Wildland and Resources Studies Series. McGill-Queen’s Press. Montreal. P.Q.

Nagy, M. Interview with CBC News (2013). “Think you’re eating tuna? Think again.”

Stroink, M.L. & Nelson, C.H. (2012). Understanding traditional food behaviour and food security in rural First Nation communities: Implications for food policy. Journal of Rural Community Development 7(4), 24-41.

Stroink, M. & Nelson, C.H. (2009). Aboriginal health learning in the forest and cultivated gardens: Building a nutritious and sustainable food system. Journal of Agromedicine, 14:263-269.

The authors acknowledge Ralph Martin, Loblaw Chair of Sustainable Food Production at the University of Guelph, for his leadership in establishing the Sustainable Food Research Group, and for initiating their collaboration.

Note: The A\J website automatically alphabetizes authors by first name. The authors of this article originally appeared in the following order: Kristen Lowitt, Mike Nagy, Connie Nelson, & Dean Bavington.

Learn more about how a successful CSF operates at offthehookcsf.ca, or cast into Canada’s network of CSFs at localcatch.org. Stay informed about small-scale fisheries via the Ecology Action Centre’s marine issues committee blog at smallscales.ca.

Kristen Lowitt is a doctoral candidate in Interdisciplinary Studies at Memorial University. Her research focuses on changing fisheries and the implications for community food security on Newfoundland’s west coast.

Connie Nelson is a professor at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Ontario, and director of the Food Security Research Network. Her research focuses on building resilient local food systems.

Dean Bavington is a Geography professor at Memorial University in St. John’s, Newfoundland, and the author of Managed Annihilation: An Unnatural History of the Newfoundland Cod Collapse (2010, UBC Press).

Mike Nagy is a sustainability consultant specializing in eco-certification, traceability and labelling of seafood in Canada and holds a Master of Environmental Studies from Wilfrid Laurier University.