ON APRIL 17, Canada’s Minister of Natural Resources Joe Oliver stood behind a podium on the warehouse floor of Automatic Coating Limited’s Centre for Pipe Line Coating Innovation, in the industrial heart of Scarborough. Renowned for its technologically advanced and fully automated production lines, ACL has made a name for itself by developing, among other things, new coatings that protect oil and gas pipelines from corrosion.

ON APRIL 17, Canada’s Minister of Natural Resources Joe Oliver stood behind a podium on the warehouse floor of Automatic Coating Limited’s Centre for Pipe Line Coating Innovation, in the industrial heart of Scarborough. Renowned for its technologically advanced and fully automated production lines, ACL has made a name for itself by developing, among other things, new coatings that protect oil and gas pipelines from corrosion. Given the heated public debate about the fate of the proposed Northern Gateway pipeline across central British Columbia, ACL was the perfect place to pitch the latest in a long list of changes, including Bill C-38, the Harper government’s 425-page omnibus budget bill that will gut some of Canada’s most important environmental safeguards. These changes will all determine how industrial development will affect Canada’s forests, waterways and people.

As is the Harper government’s wont, the scene was set with precision. Dressed in the shades of water – a deep-ocean blue suit and pale blue tie, separated by a shirt the colour of roiling surf – the dapper statesman made his pronouncements in front of four Canadian flags and the giant, deftly coated pipelines for which ACL is famous. The sign fronting the podium read, “Jobs, Growth, Prosperity.” There was not a plant or pond in sight.

Under the rubric of “Responsible Resource Development,” Oliver has promised to “streamline” and “modernize” the environmental assessment process for industrial projects large and small, all without compromising the health of a Canadian environment that evokes reverence around the world. “The Harper government’s plan for Responsible Resource Development will create good, skilled, well-paying jobs in cities and communities across Canada,” he told a gaggle of journalists and ALC staff. At the same time, Oliver said we will maintain “the highest possible standards for protecting the environment,” while preventing “long delays in reviewing major economic projects that kill potential jobs and stall economic growth by putting valuable investment at risk.” The rhetoric of the federal Conservatives makes it clear that overhauling the system is critical to keeping Canada competitive in the global marketplace.

It sounds impressive. After enduring a spate of tar sands approvals that drove up construction costs fast enough to force oil companies to put projects on hold because of budget overruns, and despite recent evidence that the government’s monitoring program had failed to notice significant levels of pollution in the tar sands region, Oliver is promising even more large-scale industrial development, permitted faster, and with no undue impacts on the environment.

The timing couldn’t be better. The Harper government forecasts more than 500 major energy and mining projects over the next decade, representing half a trillion dollars of new investments and hundreds of thousands of new, high-paying jobs. The world is our oyster: a tar sands revolution, a booming economy and energy superpowerdom are on the horizon.

It would be churlish to quibble. Still, let’s.

The integrity gap

The fundamental assumption in the argument for streamlining the way Canadian governments protect the environment is that, however clunky, the system works. Just ask Canada’s federal Environment Minister Peter Kent. After assuring a packed audience at the Calgary Chamber of Commerce on January 26 that he is not one of those “environmental radicals” on Oliver’s black list, Kent explained that Environment Canada is a world-class leader in “developing, implementing and enforcing national, science-based environmental regulations and standards.” The trick, he maintained, was to optimize Environment Canada’s effectiveness through efficiency. “While our commitment to protecting Canada’s natural heritage is absolutely firm and unwavering,” he said, “we’ve stepped up our effort to ensure that we are working to improve environmental performance in a way that supports jobs and economic growth.”

If only it were so. In fact, Canada is one of the most ineffectual environmental protectors in the developed world. David Boyd, an expert in Canadian environmental policy and author of Unnatural Law: Rethinking Canadian Environmental Law and Policy, wrote recently that it is “an incontrovertible fact” that Canada is an international laggard in environmental policy and practice. He references several studies by some of our most prestigious academic institutions. In 2009, the Conference Board of Canada ranked Canada 15th out of 17 wealthy industrialized nations on environmental performance. In 2010, researchers at Simon Fraser University ranked Canada 24th out of 25 OECD nations on environmental performance. Yale and Columbia ranked Canada 37th in their 2012 Environmental Performance Index, behind major industrial economies including Germany, France, Japan and Brazil. Worse, our performance is deteriorating: we rank 52nd in terms of progress over the 2000-2010 period, behind environmental powerhouses such as Armenia, Zambia and Myanmar.

And things appear to be getting much worse. Maurice Strong, secretary general of the ground-breaking 1992 Earth Summit and a recognized leader in the international environmental movement, said recently that the current Canadian government “has been the most anti-environmental government that we’ve ever had, and one of the most anti-environmental governments in the world.”

Nowhere are these problems more apparent than in the realm of environmental assessment. In theory, environmental assessment is an effective decision-making tool that requires governments and industrialists to integrate environmental considerations into planning and decision making. Subsequent review processes then allowgovernment authorities, aided by public participation, to check the work, evaluate the consequences and decide on approvals and permitting conditions. It is, in other words, a transparent process that ensures environmental and social impacts are rigorously considered alongside the anticipated economic benefits. It also happens before decisions are made that could have long-lasting adverse impacts on Canada’s social fabric and natural heritage.

Until the Jobs, Growth and Long-term Prosperity Act (aka Bill C-38) was passed in June, major project proposals could trigger environmental assessments at both the federal [under the 1992 Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (CEAA)] and provincial levels. Following the Canada-Alberta Agreement on Environmental Assessment Cooperation in 2005, environmental assessment reviews for major projects have usually been a combined effort, conducted by what’s called a joint review panel. Ostensibly, this process assists bureaucrats in determining whether projects should be approved, and if so, under what conditions. The goal is to prevent harmful projects from being built, and to ensure approvals are less environmentally and socially risky.

It’s worth pointing out that despite its flaws, there were many reasons to recommend the former version of CEAA over its provincial counterparts, especially Alberta’s. CEAA’s preamble stated that “environmental assessment provides an effective means of integrating environmental factors into planning and decision-making processes in a manner that promotes sustainable development.” CEAA mandated the consideration of cumulative effects and impacts on the capacity of renewable resources (such as fish and forests), “to meet the needs of the present and those of the future.” In particular, the federal Fisheries Act included strong provisions to protect fish habitat, which is an important part of most federal environmental assessments.

The original CEAA also provided more opportunity for public participation. In Alberta, an individual or organization must satisfy a narrow definition of being “directly affected” to participate in environmental assessment hearings. CEAA, in contrast, assumed that every member of the Canadian public had an interest in responsible, sustainable development and ensured them the right to participate in joint panel reviews. This is a vital and powerful part of effective assessment (and, indeed, a healthy democracy), assuring that Canadians can inform decisions about major projects like tar sands mines and oil and gas pipelines.

Despite CEAA’s superiority over Alberta’s rather less diligent requirements, it hasn’t delivered on its promise of ensuring that Canada moves toward more sustainable development. More than 95 per cent of all projects are approved, some of which clearly have resulted in significant ecological harm, and many assessments are either incomplete or faulty. Worse, governments often ignore the recommendations of the joint review panel altogether, and it’s unclear whether project proponents implement the mitigations upon which their approvals were granted.

In 2003, William Leiss, former president of the Royal Society of Canada and one of Canada’s foremost experts in environmental risk, wrote in The Integrity Gap, “Canada has an embarrassing and consistent record of failure in credible environmental assessment for high-profile, large projects” (like tar sands mines).

Developing in the dark

Scott Vaughan, Canada’s Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, also doesn’t share Kent’s rather sanguine appraisal of Canada’s environmental record, at least as it relates to environmental assessment in the tar sands. Vaughan, whose job is to inform Parliament about how well the federal government is managing its environmental and sustainable development commitments, completed two audits related to environmental assessment in 2009 and found “a number of serious deficiencies in how assessments are planned, carried out and followed up on.” Last October, he released another damning report examining whether environmental assessments had adequately considered the cumulative environmental impacts of five of Alberta’s tar sands mines – Suncor’s Project Millennium, Canadian Natural Resources’ Horizon Oil Sands Project, Shell’s Jackpine Mine Project and Muskeg River Mine, and Imperial Oil’s Kearl Oil Sands Project. The results were sobering.

According to Vaughan’s report, Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Environment Canada failed to “consider in a thorough and systematic manner the cumulative environmental effects of oil sands projects in that region.” Federal government staff “repeatedly pointed to gaps in environmental data and scientific information related to the potential cumulative impact of oil sands projects on water quantity and quality, fish and fish habitat, land and wildlife, and air.” They pointed to “insufficient information on the potential acidification of water bodies in northern Saskatchewan; a lack of baseline data for assessing the impact of projects on wildlife corridors; and uncertainties and incomplete information regarding the impacts of stream flow rates, tailings [ponds] and other water issues, such as the potential impact of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons extending as far as Great Slave Lake.” And yet, despite these shortcomings, every single one of the projects was approved.

For these reasons, the Pembina Institute and three other environmental organizations challenged the joint review panel’s 2007 finding that Imperial’s Kearl Oil Sands Project would not likely result in significant adverse environmental effects. “The joint panel has rubber-stamped another oil sands megaproject in the absence of clear answers about how to restore wetlands, rehabilitate toxic tailings ponds, protect migratory bird populations, or address escalating greenhouse gas pollution,” said Pembina Institute’s policy director Simon Dyer at the time. “The joint panel said it was ‘deeply concerned’ about the failure of government to implement systems to protect the environment, but nonetheless decided to give the Kearl oil sands project the green light.” It was a long shot – one skirmish in a David versus Goliath battle to clean up the tar sands, which grows exponentially as the years pass – but the environmentalists stood before the Federal Court with their stones and slingshots anyway.

The decision, not surprisingly, largely went industry’s way. Although Madam Justice Tremblay-Lamer of the Federal Court directed the joint panel to provide substantiation that greenhouse-gas emissions from the Kearl project would not be significant, she chose to defer to the panel’s opinion that other environmental impacts were either insignificant, or could be mitigated with a suite of new and promising technologies. She decided that the environmental groups were simply challenging the quality and thoroughness of the evidence in front of the joint panel, and without actually vetting the evidence, she ruled that the panel was a dependable expert. She didn’t consider whether the evidence in the environmental assessment was accurate or persuasive; she simply concluded that it was not her place to judge.

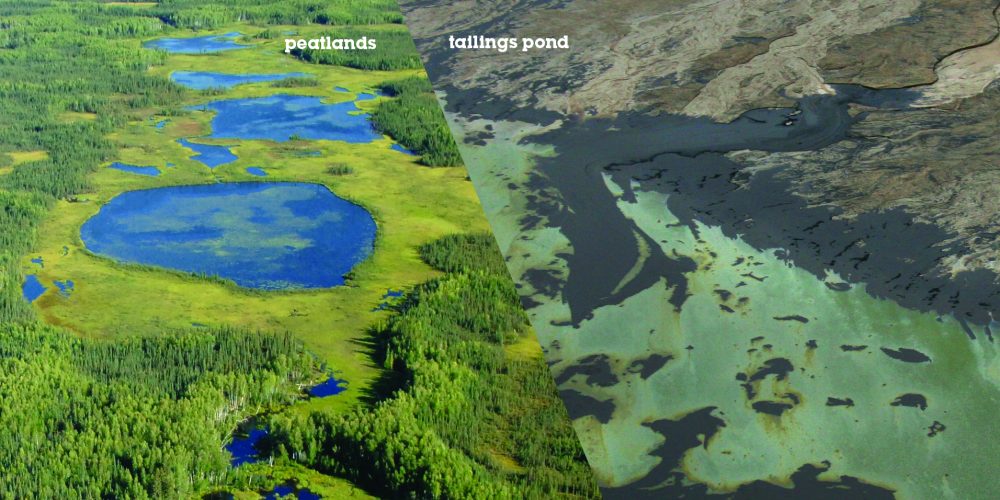

In doing so, Tremblay-Lamer accepted Imperial’s claim that peatlands, which are destroyed by tar sands mining, could be reclaimed, even though Imperial agreed with the environmental groups’ assertion that how to reclaim peatlands “is not even known in general terms.” Indeed, Alberta Environment’s own 2005 Provincial Wetland Restoration/Compensation Guide concluded that it is almost impossible to fully replicate the complexity of a natural wetland ecosystem. Canada’s preeminent freshwater scientist David Schindler [see “Schindler’s Pissed,” page 19] and his colleagues reached a similar conclusion, publishing research that confirmed, “reclamation of peatlands has so far proven impossible,” and any claims to the contrary are “clearly greenwashing.”

Likewise, Tremblay-Lamer implicitly agreed with Imperial’s contention that, some 60 years hence, it would repair the ecosystem by simply covering Kearl’s massive toxic tailings ponds with several metres of freshwater. This would create what industry euphemistically calls “end-pit lakes” (EPLs), which purportedly would support fish.This is a dubious claim that even the industry-funded Cumulative Environmental Management Association (CEMA) has said “raises issues of concern,” because “historical data are insufficient to determine a realistic outcome of the final features of EPLs,” and “a fully realized EPL has yet to be constructed.”

The panel recognized that the transformation of tailings ponds into healthy end-pit lakes was dependent on the development of future science and technology. Yet the judge acknowledged that while there was “some uncertainty with respect to end-pit lake technology, the existing level of uncertainty is not such that it should paralyse the entire project.” The precautionary principle, which CEAA required be exercised in all circumstances, was ignored in favour of a cornucopian belief in science and technology to solve, at some uncertain date in the future, any and all problems.

“Canadians have a right to know about the high environmental cost that accompanies oil sands expansions and the impacts of other land-uses in the region,” wrote Dyer in a recent Pembina Institute blog post. “Given the proposed pace of oil sands expansion, companies must provide decision makers and Canadians with a clear picture of the significant trade-offs that would be required to support such a rapid scale-up of production.”

Irresponsible resource development

Not surprisingly, the president of Automatic Coating Limited was thrilled about Minister Oliver’s speech at his Scarborough plant. “We support the government’s announcement today,” said Brad Bamford. “It will herald a new era in streamlining projects in the oil and gas industry and that means more jobs and greater prosperity in Ontario manufacturing.” Both the Mining Association of Canada and the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers issued similar statements of approval for Bill C-38, which became law in June.

The problems inherent in the federal environmental assessment process to date make it clear there is room for improvement. But a growing chorus of critics are concerned that despite industry’s approval, the Harper government’s omnibus budget bill, which replaces CEAA with a new and very different version called CEAA 2012, will have disastrous consequences. While there isn’t room enough here to explore all the implications, it’s clear that CEAA 2012 will substantially weaken Canada’s federal environmental assessment and review process.

According to Robert Gibson, professor and associate chair of graduate studies in the University of Waterloo’s Department of Environment and Resource Studies, the comprehensive environmental assessment currently required at the federal level has been replaced with information gathering on a narrow range of factors. Decisions about the application of assessment requirements to particular projects, and about the scope of required assessments, are now left to the discretion of politicians and bureaucrats, determined after the projects have been planned and designed. Rather than providing the quick and easy predictability that industry demands, CEAA 2012 will actually increase uncertainty at the project approval stage. And because cabinet gets to make the final decision on whether or not to approve major energy projects, politicians can give the green light to any project, however significant its adverse effects may be. Such decisions would be discretionary, and the evidence and reasoning behind trade-offs would be made behind closed doors.

“The actual provisions of the CEAA 2012 would virtually eliminate federal level environmental assessment, except insofar as it might continue under other legislation,” says Gibson. “And what remains could not deliver efficient or effective assessment.”

Also troubling is the fact that the Jobs, Growth and Long-term Prosperity Act downloads much of the responsibility for environmental assessment to provincial governments. The environmental assessment process in most provinces, including Alberta, is weaker than the original federal process. Also, Alberta doesn’t have adequate- legislation to protect certain environmental factors, including fish habitat. To make matters worse, the habitat provision in the Fisheries Act – one of the strongest pieces of legislation in Canada’s underwhelming rule book, which has been giving industry fits for years – has been weakened by not requiring a rigorous and transparent assessment of the impacts on aquatic and threatened species. These changes leave a gap in the environmental approvals process large enough to build a pipeline through.

“The overall effect of CEAA 2012 will collectively set back federal environmental assessment law by at least 40 years,” explained Richard D. Lindgren, counsel for the Canadian Environmental Law Association, this spring, before the budget bill became law. “In addition to gutting CEAA, the budget bill also proposes sweeping changes to the Fisheries Act, Species at Risk Act and other federal environmental statutes. This is why we view the budget as an unacceptable attack on the environmental safety net that exists in law at the federal level, and it’s clear the intention is to expedite energy projects, rather than protect the public interest.”

The federal government’s characterization of the need for change, and its claims that the proposed changes will not undermine – and may even improve – environmental protection in Canada are specious at best. The reality is that Canada needs a more rigorous, science-based environmental assessment process to ensure it meets the spirit of the original CEAA. Despite its flaws, it was the cornerstone of environmental protection in our home and native land.

This is no trifling matter. Without a strong environmental assessment act, we will never be able to build the kind of sustainable economy that Canadians claim to want. Worse, we leave the door open to a tsunami of environmental degradation that will leave our children and grandchildren with a debt they will never be able to overcome.

Tar sands or oil sands? Check out our web exclusive excerpt from Little Black Lies, the forthcoming book by Jeff Gailus, that expands on the complicated history of the seemingly interchangeable terms.

Jeff Gailus is an award-winning writer and author of The Grizzly Manifesto and Little Black Lies: Corporate and Political Spin in the Global War for Oil.