Plastics should be a food group all on its own since most of the food we eat contain micro- and nanoplastics. Whether we like it to or not, plastics have become a hidden part of our diet. Fruits, vegetables, meat, seafood or bottled water are becoming laced with tiny pieces of plastics. While microplastics dominate the oceans, they along with nanoplastics dominate the soil.

Plastics should be a food group all on its own since most of the food we eat contain micro- and nanoplastics. Whether we like it to or not, plastics have become a hidden part of our diet. Fruits, vegetables, meat, seafood or bottled water are becoming laced with tiny pieces of plastics. While microplastics dominate the oceans, they along with nanoplastics dominate the soil. Microplastics have made waves in environmental awareness of their impact on the oceans and the aquatic life that consume them. However, they’ve been affecting us right on our plates in the terrestrial environment and in the air. Only recently have studies shown that they are indeed in our fruits and vegetables due to plastic contamination of soil and water used for crop irrigation.

Plastics have now been proven to be found inside fruits and vegetables

Source: Unsplash

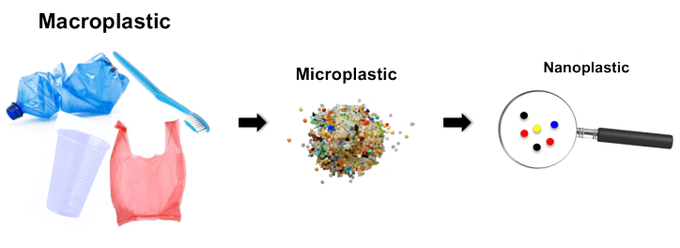

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), microplastics are plastics 5 mm long. Whereas, nanoplastics are smaller than a micron, according to the Nature Research Journal. That’s the size of a grain of rice compared to that smaller than a human red blood cell (5 microns), respectively. The latter is smaller than the diameter of a human hair strand (75 microns)- that’s microscopically small. Nanoplastics can, therefore, have a greater negative impact in the environments that they exist as they cannot be seen with the naked eye like microplastics.

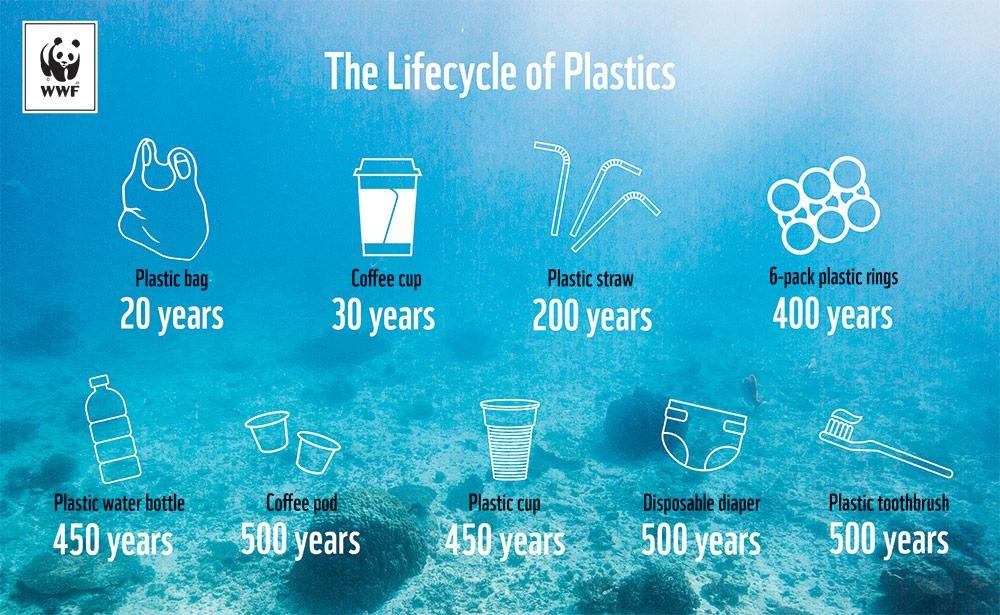

How did plastics get into the soil? The terrestrial environment is littered with macroplastics such as bottles, plastic bags, single-use straws and cutlery. The aging process of plastics including their degradation and disintegration rates differ based on the item. This process breaks down macroplastics into micro- and nanoplastics. According to the World Wildlife Fund, coffee pods can take up to 500 years to decompose, plastic bottles, 450 years and plastic straws 200 years. As with any object, the larger the surface area the easier it is to cleanup. However, once macroplastics are broken down into microplastics, anything of that size and beyond has irreversible impacts.

The lifespan of plastics after they are disposed of

Source: World Wildlife Fund

Therefore, downsizing the (plastic waste) problem is upsizing the negative environmental and human health impact. Globally, approximately 32% of plastic waste find their way into the soil and aquatic ecosystems. Terrestrial microplastics are more dominant than ocean plastics and depending on the environment can be 4 to 23 times higher according to a study by German researchers. While more research needs to be done on the impacts of microplastics in terrestrial ecosystems we can certainly expect that over time the outcome would not be healthy. When would society realize that the plastics we use and dispose of improperly are affecting our health?

Nanoplastics are formed from degraded litter that is poorly disposed of

Source: Plant Experts

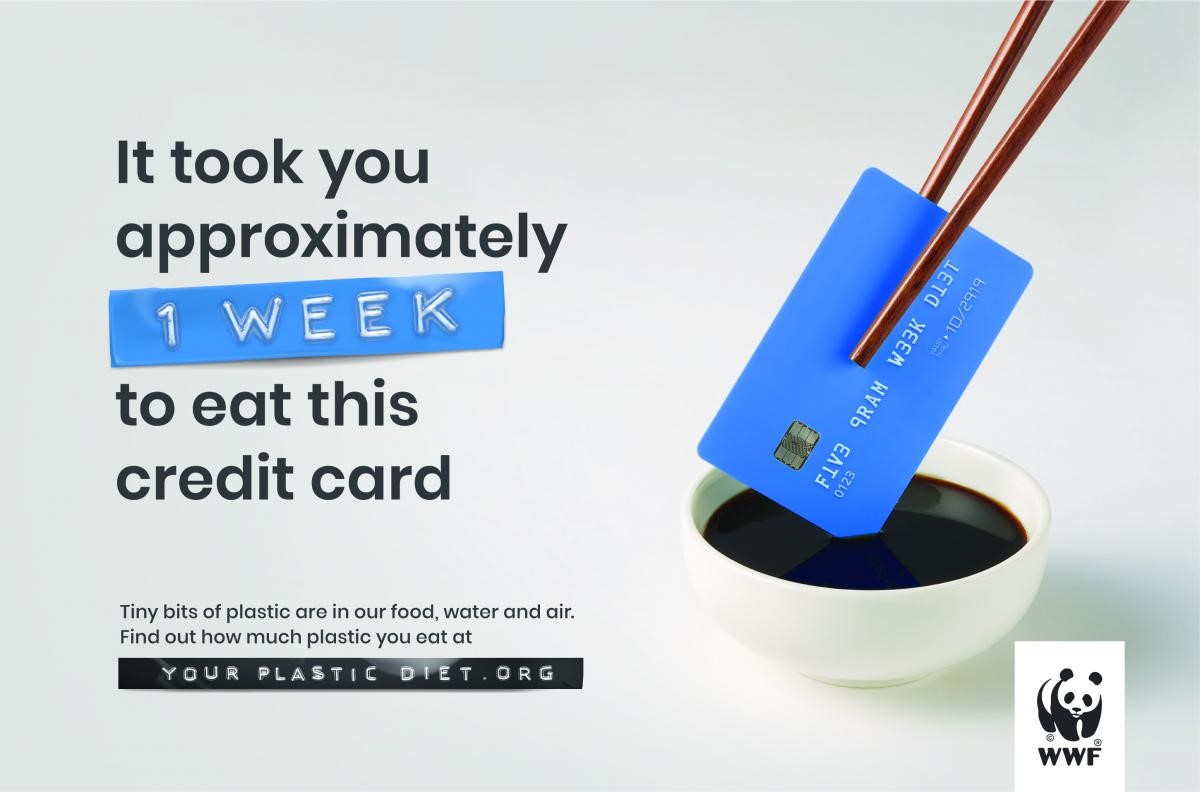

According to National Geographic, microplastics have been found in other food including seafood, salt, honey, sugar, honey, alcohol and beer. A study done by the University of Newcastle, Australia and commissioned by the World Wildlife Fund found that on a weekly basis, we can be consuming 5g of microplastics- that’s equivalent to the weight of a credit card.

Source: Kancil Awards

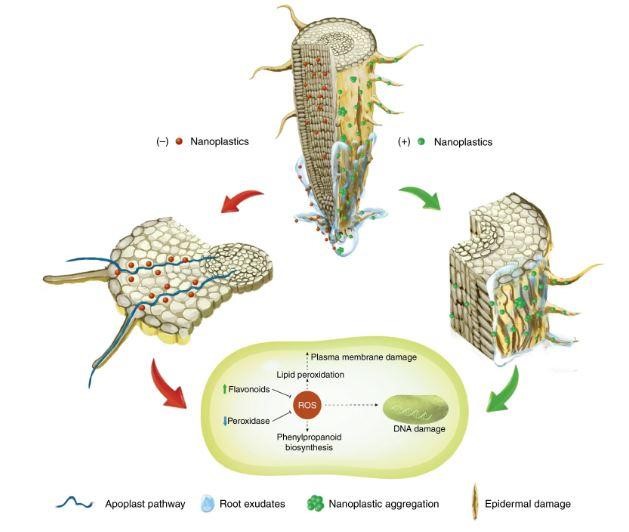

A study published in June 2020 by Nature Nanotechnology Journal showed that nanoplastics can accumulate in plants which can affect food safety and crop yield. The higher the nanoplastic concentration in the soil, the shorter the plant roots and lower the weight (41.7%- 51.5%). The electrical charge of the nanoplastics whether positive (found in root tips) or negative (found in apoplast and xylem), determined their location within the plant. The charge also influenced how much damage was done and whether the nanoplastics were absorbed by the plant. The location of the positively charged particles affected the plant’s health despite being in lower concentrations compared to negatively charged nanoplastics which were found in areas that transported fluids like water and essential nutrients within the plant.

Differently charged nanoplastics being uptaken by plant roots and the plant’s response

Source: Nature Nanotechnology

We’ve known for years that plastics are in our air, ocean and soil. And now finally we have the proof plastics are in the fruit and vegetables we feed to our children.” Sian Sutherland Co-Founder of Environmental Campaign Group A Plastic Planet

Plants have been uptaking nanoplastics with water through their roots from the soil and contaminating our fruits and vegetables. Another recently published study in 2020 in the Environmental Research Journal on this topic by Dr. Conti and research team, showed that micro- and nanoplastics, depending on their size, are capable of penetrating plant cells in their roots, stems, leaves, seeds and fruits. Carrots appeared to be the most plastic-contaminated vegetable (with very small plastics 1.51 μm), while apples were the most plastic-tainted fruit. However, the study also found them existing in pears, broccoli and lettuce which are ranked in order of most to least contaminated amongst apples and carrots at both ends of the spectrum, respectively. Lettuce was found to have the largest pieces of microplastics at 2.52 μm. Compared to vegetables, fruits had a higher concentration of microplastics due to their age of trees (e.g. years vs. 60-75 days for vegetables like carrots), their greater complexity and size of their root system. Accumulation of nanoplastics of appropriate size can delay flowering and growth as they affect the uptake of essential plant nutrients.

We are aware of the culprit and their entry point into plants, but how are they moving into the food we eat? A study on the uptake of microplastics in crop plants such as wheat and lettuce published in July 2020 in the Nature Sustainability Journal confirmed that movement is promoted through the act of transpirational pull. The higher the pull, the greater the force allowing nano- and microplastics to move from the roots to the edible above-ground parts of the crops easily. The study found that these plastic particles had some degree of flexibility which made it easier for them to squeeze into root cells. This study also highlighted that wastewater which is usually used to irrigate crops globally are also contaminated with microplastics and are another source apart from those in the soil. Crops grown in fields contaminated with sewage sludges or wastewater treatment discharges are prone to having more micro- and nanoplastics.

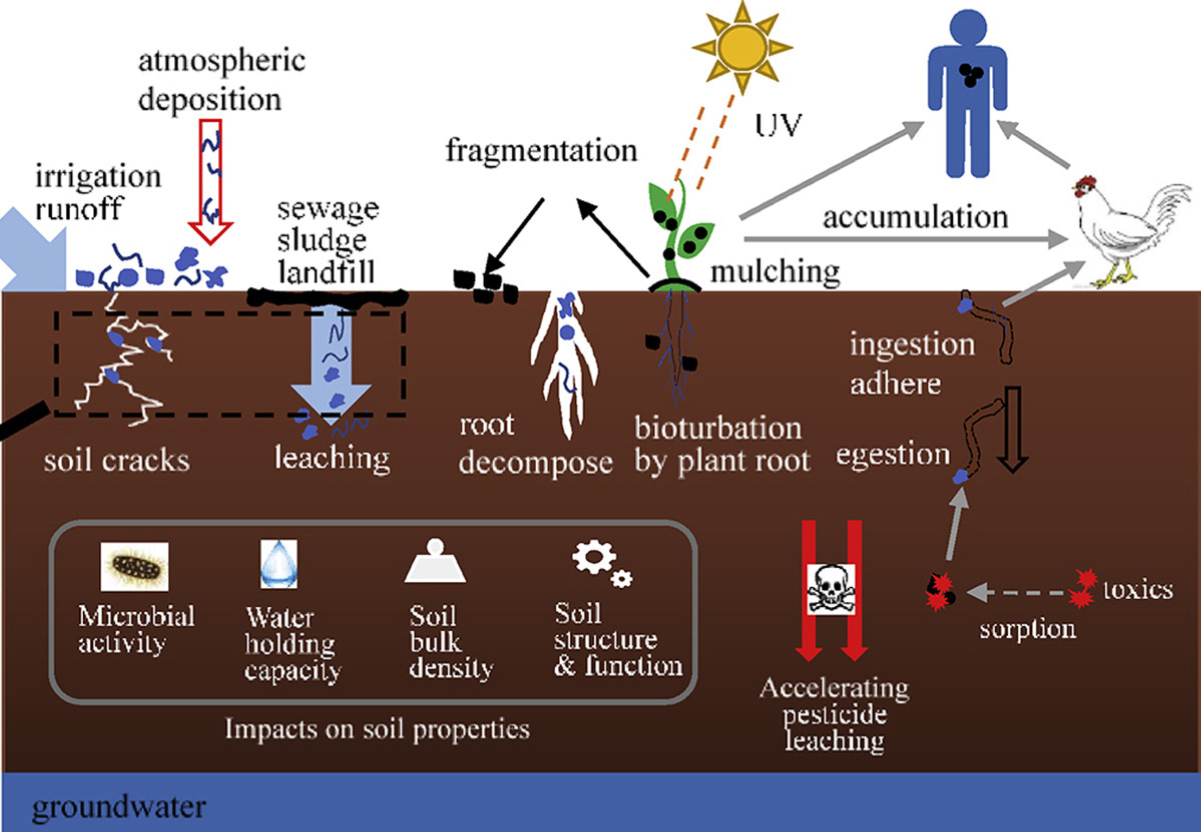

Potential sources, transport pathways and ecological risks of plastics in the soil

Adapted from Source: Environmental Pollution Journal

If it is getting into vegetables, it is getting into everything that eats vegetables as well, which means it is in our meat and dairy too”. Maria Westerbos Founder of environmental group Plastic Soup Foundation

While fruits and vegetables are potentially the most commonly consumed food source globally compared to meat and seafood, it’s not something that can be eliminated from our diet. At present, the impacts of nanoplastics on human health are unknown but can imaginably be negative.

With the nutritional value of fruits and vegetables being compromised, I’m curious to see what solutions, rules and regulations will be established in the future and concerned about the resultant health impacts.

Once again humans have managed to allow their pollution to come back to bite them in the food that they bite. Since fruits and vegetables cannot be removed from our diet anthropogenic induced pollution can only be stopped if industries reduce the production of plastics, governments impose bans on single-use plastics, consumers do not litter but recycle when possible or attempt to be Strong and Plastic-Free. Similarly, switching to environmentally friendly alternatives and looking into the 10 R’s for discontinuing the plastic cycle may help reduce the quantity of plastics we use in our daily lives.

***

To learn about the existence of 1.9 million pieces of microplastics in 1m2 on the seafloor, see the article Two Million Too Many.

Akin to measuring your carbon footprint, the World Wildlife Fund and Your Plastic Diet have created a short Plastic Test to help you determine how much plastic you’re consuming and what you can do about it.

Shanella Ramkissoon is a Masters in Environment and Sustainability candidate. Her background is in the field of Environmental Science and Environment and Resource Management. Her interests lie in environmental conservation, especially for marine species such as coral reefs, turtles and dolphins. In her free time, she enjoys landscape photography, baking and art and craft projects.