In 1925, at the Crystal Palace exhibition hall in London, esteemed judge AW Smith of the Lizard Canary Association, was introduced to the newest sensation in the canary world. Mrs. Rogerson of Cheltenham in Gloucestershire had been attempting to create a miniature crested canary and determinedly pursued her goal. At the exhibition, Mrs. Rogerson unwinged her creation, an original breed achieved by crossing crested Roller Canaries with Border Canaries.

Judge Smith was suitably impressed and “recognized Mrs. Rogerson’s original strain as a new, unique, and distinct breed. He went on to encourage development of the (breed) … and he later developed the first breed standards.”

Mrs. Rogerson’s new breed was the Gloster (for Mrs. Rogerson’s home shire) Fancy Canary, and it came in two versions, the Gloster Corona and the Gloster Consort.

The Gloster Corona (left) and Gloster Consort (right) (images from Animal World)

The Gloster Corona was, as its name suggests, crowned with crested plumage, the first to catch the eyes of canary admirers already drawn to its pleasant singing and good-hearted demeanour. The Gloster Consort was, as its name suggests, a bit less regal-looking and, if it were human, possibly harbouring a grudge for being denied the crown and the attention. But each version was equally important and Mrs. Rogerson’s creation, coming in an age when canaries were admired for their singing – and for their utility to us as harbingers of doom in our coal mines – developed a strong and loyal following, persisting to this day as a leading canary-fanciers favourite.

Four years before the birth of the Gloster Consort, a young man was born on a Greek island who would, as fate would have it, come to learn a thing or two about birds. And, interestingly, nine years after the exhibition, a young man would be born in a town in southwest Ontario who would, as fate would have it, also come to learn a thing or two about birds.

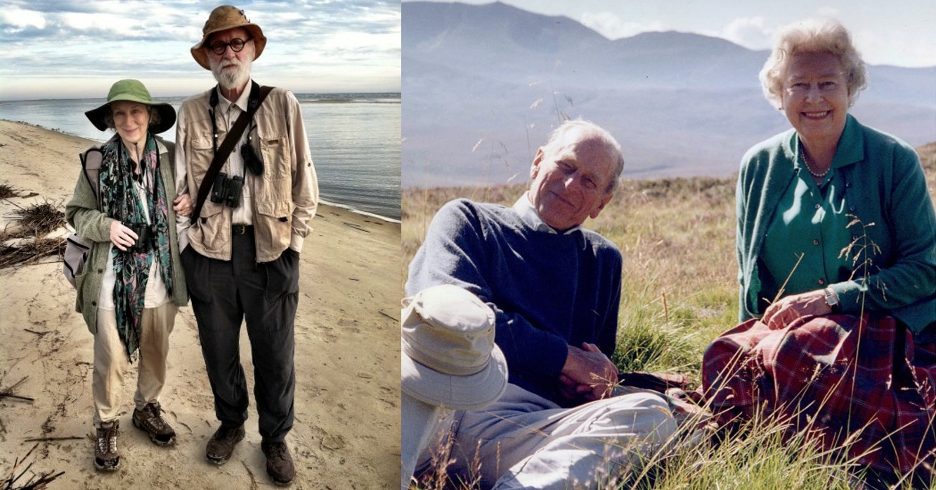

Margaret Atwood and Graeme Gibson (left), Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip (right)

***

Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark was born on the Greek island of Corfu, and came to international prominence when his acquaintance with Princess Elizabeth of Great Britain became more than an acquaintance. In 1946, King George VI gave his permission and blessing to the marriage of his daughter, the presumptive heiress to the throne, to this tall, handsome young princeling who’s lineage could be traced back to the German principalities, a lineage shared with his betrothed (and with many of the sovereigns of Europe, in fact).

Prince Phillip was a constant presence in my life. I was born 10 years after Phillip’s Queen ascended to the throne and I have watched from afar as a loyal subject of his (and my) Queen and an admirer of his for the way in which he navigated his life. In many ways, the dynamic that underpinned the relationship between Phillip and Elizabeth was mirrored in my own world as my mother, ‘Queen May’, ruled the realm with the genial assistance of her consort, my father George. My Dad, a former Royal Marine Commando, stayed at home during most of my childhood while my Mom went off to work at the hospital, or the modelling agency, or the nursing home. My Dad did the cooking and cleaning, along with whatever odd job that he’d pick up in his former trade as a carpet-master and flooring specialist. And he did it with a smile on his face that only broadened when he’d meet his grandchildren in his daily parade as the King of Queen Street. A man who could (and probably did; he always hedged when asked specifically) kill somebody with his bare hands, hands that were scarred and calloused from a life’s labour, would stop everything and drop everything to pick up a beaming grandchild and whisk her up into an impromptu dance. And then he’d hurry home to ensure that the supper was on and the place was set for my Mom’s return from work, the happiest part of my Dad’s day.

(George and May McConnachie, circa 1960s)

In most respects, I saw this as completely normal and assumed that every father was so hard yet soft, a sinner yet a saint. Sometimes, though, I’d question how my Dad put aside his masculinity as a member of the supposed superior sex to assume what was a traditional feminine role, the helpmate, in the very patriarchal society of the 1960s and 70s. Did it make him more or less of a man? And what lessons would I draw as I grew into my own manhood?

In these questioning times, and perhaps sensing my unease, my Dad and I would start talking (both of us well-known non-stop talkers) about the military career of Prince Phillip and the important roles that he played for Canada, Scotland and the rest of the British Empire. How he carried himself with great dignity. How he put his family first. How he took the most masculine step possible, to take a step back to allow someone else to shine, and to do so with a sense of duty and responsibility that was absolutely necessary to the role. Being the consort of a Queen was no easy task, but there always seemed to be a smile on Phillip’s face as he beamed at his Queen and she at he. It seemed as real to me as the love that was demonstrated between my parents, and I knew that my mother’s successes in this world were directly related to the scrubbing of the laundry and the seasoning of the stew, and the countless other little duties, that my father fulfilled with a joyfulness in his heart that everyone felt.

Both Prince Phillip and my Dad (and my Mom’s consort), George, were born in the year 1921. They both fought in battles in far off lands and fought battles for their families closer to home. They were faulty human beings – as we all are – but each managed to persevere through their own limitations and life’s challenges to be the strongest supporters and the loudest fan of their respective Queens. It is a lesson that I have taken to heart – and taken home to roost whenever I have been fortunate enough to be joined in my own life’s journey by a Queen.

***

Phillip of Greece and George of Glasgow shared many traits and commonalities. One of the most obvious to me was the love of the outdoors, a respect for nature and an understanding that we human beings are but one small species in a giant ecosystem called life-on-earth. I used to watch the annual BBC specials on the Royal Family, and invariably there’d be a mention of Prince Phillip’s conservation efforts, specifically in the area of birds. My Dad kept his conservation efforts nearer to us, opening the back door in the morning and stepping out to feed his ‘wee beasties’, the squirrels, chipmunks and birds that would soon be eating their own meals from his hands. He’d share wisdom straight from de Saint-Exupéry about the importance of stewardship, not the fleeting kind but the long-tailed kind of stewardship that came with as many tears as triumphs. He’d share tales from his own wartime adventures, the birds that he saw in Egypt or the crows in the bell towers in Italy. He’d sing songs that he’d make up, swearing to me that he was only replicating what he’d been taught by the birds. To this day, I’ll engage in singathons with the jays and others in the trees near me (of which they might not always appreciate), just to recall the feeling of, that moment of, my hero, my father, being in tune with nature. And everything being good in the world

“To this day, I’ll engage in singathons with the jays and others in the trees near me (of which they might not always appreciate), just to recall the feeling of, that moment of, my hero, my father, being in tune with nature. And everything being good in the world.”

My Dad was a near-urban wildlife aficionado, a product of his own upbringing in the tenement blocks of Glasgow. He would sally forth with a backpack on his back as a boy, especially when he was visiting relatives in the relatively bucolic Firth of Forth town called North Queensferry, right across from Mary Queen of Scots’ castle in Edinburgh. And the stories that he’d tell, of going up and down the moors, of splashing through the streams, and of lazing under the bright skies while watching the birds overhead and wondering if these winged creatures were actually God’s cherubim incarnate.

When my Dad talked of nature, he’d do so with a reverence in his voice, of the quiet and the peace. Of the giant trees and glistening lakes. Of the clear skies and clearer water, water that was so cool that you could quench your thirst even on the hottest day. Of the animals, large and small, that made the woods and forests their homes. And of the need to respect nature and all her parts, of which we were just one little aspect.

“You’re one in a million to me, Davey, but to the rest of the planet you’re just one of a million.”

As I got older and started reading history books about my father’s battles, I started to gain a deeper understanding of why my Dad, a man of action, would retreat into nature as a place of both solitude and rebirth. In battle, there is no peace, no quiet. In battle, the trees are torn asunder by artillery shells and the lakes stained red. In battle, there is constant thirst, a thirst for life, that is parched by the heat and the dust and the fear, and cool respites are few and far between. In battle, the woods and the forests become death-traps, for the humans and for every species, eerily devoid of bird calls but overflowing with smoke and fire and flames. And death.

Nature, alive, is full of life. Nature, alive, breathes and breeds new life. Nature, alive, is now a known antidote and remedy for those suffering from mental anguish and illness, a perfect ‘safe space’ to retreat into to undergo nature therapy. Breathing with the trees. Ebbing and flowing with the waters. Waking with the birds and drifting off to sleep to the cicadas. Meditation and introspection, a humbling that comes by appreciating your own inanity in this world full of pomposity and insanity.

Today, when I am perplexed by a problem and need to clear my mind, nothing works better than taking Zoey the dog (half border collie, half husky, all go) for a walk in the nearby nature trail here in Exeter, Ontario. I become mindful of each step we take. I become mindful of the sounds of the forest. I become mindful of the wind chilling my cheek. And, in doing so, my mind gains space from the perplexing problem. In most cases, that space and distance is enough to allow my logical thoughts to win the argument in my head and allow me to take the appropriate step(s). My emotional side has been succoured by nature. Nature becomes my consort, if you will.

***

In addition to the aforementioned Phillip and George, there’s another gentleman who embodies the spirit of being a consort in life and to life. Graeme Gibson of London (Ontario) was born into conditions more akin to George than Phillip. The son of Scottish immigrants, he and his family moved around a fair bit as a lad as they sought opportunities in this new land, but Graeme managed to take the right steps by graduating from the prestigious Upper Canada College and the University of Western Ontario. He was drawn to literature, as an outlet, and to the idea that change must be fostered, as a zeitgeist. His early works, released in the late 1960s and early 1970s, were considered by many in Canada’s literary circles as benchmarks of experiential literature, exploring important themes from perspectives not then shared by many. The works were rich in imagery and challenging in comprehension, requiring a degree of open-mindedness that narrowed mass market appeal. But Graeme understood that the purpose of literature was to serve the need of the story, and the storyteller, and if that meant limiting sales potential then so be it.

Becoming a champion of storytelling and storytellers was one of Graeme’s noble purposes, that driving compulsion to act in a manner that is not self-serving but serves the greater good.

Becoming a champion of storytelling and storytellers was one of Graeme’s noble purposes, that driving compulsion to act in a manner that is not self-serving but serves the greater good Graeme was one of the founders of the Writers’ Union of Canada, helped form the Writer’s Trust of Canada, and was a co-founder and president of PEN Canada. In the world of Canadian literature, the name Graeme Gibson became synonymous with fighting for writers’ right to write, and using their collective voices to affect change. And given that most Canadian writers exist within a very small cage of celebrity – with the resulting financial rewards that come with it – Graeme was really fighting for those who could not, through their small sales footprint (or not-yet-written first novel) earn enough daily bread to feed themselves, let alone the neighbourhood birds.

I was drawn to PEN Canada in the early 1980s as that organization began advocating for causes that resonated with my still-developing soul. PEN Canada’s mission:

PEN Canada celebrates literature, defends freedom of expression and aids writers in peril.

There seemed to be two voices that I heard most frequently from PEN. Graeme Gibson was the fiery organizer and orator. Margaret Atwood was the voice from upon high, a Canadian literary author with truly global impacts, and especially important in the areas of equal rights, civil rights and the right to have our voices heard. I could hear his voice but I saw her eyes, those eyes that seemed capable of reproach as stinging as anything she could have written. “Must be tough to be married to her,” my Dad chuckled as we watched the news, adding “and I should know!”

In my life’s journey, I got a chance to dabble in the world of Canadian literature during my time working as the publishing director of the NHL. One year, we released TOTAL HOCKEY encyclopaedia and HOCKEY FOR DUMMIES, both of which rocketed up the charts of Canadian Non-Fiction Bestsellers. I got invited to a few events, rubbed leather-patched elbows with the literati, and learned, to my delight, that the loud tall organizer was the one married to the Queen of Canadian literature. And then paid a bit more attention whenever either would pop up in the news.

At some point, I began to wonder what it must have been like to be married to Margaret Atwood, Canada’s Nobel-winning writer. Especially given that Graeme was a writer himself. How did he manage to be both a fiery advocate and soulful supporter?

How do you dance through life with your partner without stepping on the toes of her Muses?

How do you dance through life with your partner without stepping on the toes of her Muses? How do you add and not take away from her work, being there in whatever capacity may be required? Do you interrupt to offer tea or just bring it?

This contemplative time was after my Dad had passed and during a momentary crisis in my personal life that saw me need to become a good first officer to my marital captain as she launched and developed a new business. There was a random news item from Buckingham Palace that reminded me of Phillip, and of George. And, in hindsight, it helped me to understand Graeme Gibson a little bit better, and myself in the process, too. Something about a species at risk that the Duke of Edinburgh’s conservation trust had managed to nurse back to health, all in and around the ‘annus horribilis’ suffered by Elizabeth and family.

***

So, how do you act as a consort to your partner?

The verbs in the motto of PEN Canada hold a clue:

CELEBRATE. DEFEND. AID.

In the case of Phillip of Greece, he certainly spent considerable time consoling and counselling his Queen as she underwent her travails. In the case of George of Glasgow, he’d put a pot of soup on and make sure that my Mom’s chair was ready for her return. For Graeme of London, I’m guessing that, during moments of crisis in his family, he would celebrate, defend and aid his Queen to the best of his capacities, and in a manner that given the longevity of their relationship, must have worked. Margaret Atwood didn’t get any less famous for her writing or less prodigious in her output.

Now, interestingly, much like Phillip and George, Graeme also became a conservationist and ecological admirer. In his case, Graeme Gibson was a key driver behind the creation of the Pelee Island Bird Sanctuary in Canada’s southernmost point, a near-urban natural oasis that now teems with avian life, migratory and sedentary. Graeme, like the other gentleman consorts mentioned herein, took to nature as a remedy to the noises and nuisances of city life, and perhaps to step away, if even for just a brief moment, from his duties to his Queen. The smallest bird became the biggest focal point. The nurturing, the tears and the triumphs all part of the process of grounding oneself while giving back.

And therein lies the secret, I believe, to how we humans can stop putting our needs first and become consorts to our Queen, Mother Nature.

***

Mining foreman R. Thornburg shows a small cage with a canary used for testing carbon monoxide gas in 1928. George McCaa, U.S. Bureau of Mines

In 1986, the last canary was released from service to the coal mines. In all likelihood, it was not one of Mrs. Rogerson’s Gloster Canaries, be they Corona or Consort. The Gloster Canary was specially bred for its attractiveness and appeal. The canaries that worked in the coal mines were of less exalted stock, albeit hardier than their swankier cousins.

The practice of using canaries to detect carbon monoxide in mining operations was pioneered in 1911 by Dr. John Haldane, who some describe as the ‘father of oxygen therapy’. There was solid science behind the idea, specifically:

Canaries, like other birds, are good early detectors of carbon monoxide because they’re vulnerable to airborne poisons, Inglis-Arkell writes. Because they need such immense quantities of oxygen to enable them to fly and fly to heights that would make people altitude sick, their anatomy allows them to get a dose of oxygen when they inhale and another when they exhale, by holding air in extra sacs, he writes. Relative to mice or other easily transportable animals that could have been carried in by the miners, they get a double dose of air and any poisons the air might contain, so miners would get an earlier warning.

The use of canaries as ‘early warning systems’ took root in British mining companies, and soon jumped the pond to influence North American coal miners. The canaries were not only prized by the miners for their life-saving abilities but were also welcomed for their songs. “They are so ingrained in the culture, miners report whistling to the birds and coaxing them as they worked, treating them as pets.”

The phrase ‘a canary in a coal mine’ came into popular use not long after the birds went to work. In the broadest sense, it means that something is an early warning sign of danger ahead. Al Gore applied the analogy to the concept of the extinction of species and the skyrocketing GhGs are canaries in a coal mine of an ecosystem in crisis, in this case the ecosystem that sustains human life. That ‘inconvenient truth’ that Gore was sharing helped to ignite a heightened degree of awareness of environmentalism within everyday society, and became some of the foundational learning of today’s young environmental leaders. The ones leading the research, organizing a blockade to protect the old growth forests, or running for office to affect positive legislative change.

They make these sacrifices for a greater good, beyond simply the preservation of a butterfly or bumble bee. They are sacrificing for the butterfly and the bumble bee, yes, but they do so in service to humanity, keeping a watchful eye on the hands on the Extinction Clock, readying to raise the alarm or scramble to save another last-of. Because, fundamentally, these scientists, researchers, academics and activists understand and appreciate a simple truth: humans are but one species among billions on this planet, equally (if not more) vulnerable to the changes wrought by anthropogenic climate change. Fires, floods and famines, oh my! And if it isn’t good for the canary, it can’t be good for us.

***

We humans, large in numbers but small in planetary significance, have played an outsized role in the destruction and degradation of the natural environment. And while we’ve always been a messy species, we’ve really taken it up a notch since the Industrial Revolution.

You can blame our fossil-fuel-burning machinery poisoning the atmosphere with greenhouse gasses, which contributed to raising the global temperature which eventually begat the mass extinction events that we’re now watching unspool in front of our eyes like a slow-motion train wreck. And given that we’re the most golden of the Goldilocks species, the most vulnerable to extremes and to change in a time of extreme change, we should probably be paying more attention and taking more actions.

Credit: Ed Himelblau, The New Yorker

Start by birdwatching. We are far too zoomed in on our own daily minutiae to appreciate the larger world around us, and the changes that threaten our very existence.

We need to turn the binoculars around and stop demanding that EVERYONE LOOK AT US! We need to become passionate observers of the planet’s beautifully complicated ecosystems, large and small, near and far.

We need to turn the binoculars around and stop demanding that EVERYONE LOOK AT US! We need to become passionate observers of the planet’s beautifully complicated ecosystems, large and small, near and far. We need to watch the birds as they go about their daily lives. We need to listen to the birds as they call to each other, this song a love poem, this song an elegy. We need to learn about the birds, and from the birds, where they live and why. We need to go to where the birds are and to build welcoming spaces for the birds where we are. There is so much we need to know and an incredible urgency to do so.

We, as humans, need to understand and appreciate the fact that ‘we’re all in this together’ is more than a motto to survive the pandemic. It’s a reminder that we are in a codependent relationship with the natural world – and we humans are more dependent upon the planet than the planet is on humans. We will need all the birds and all the bees that we can to be our allies in our survival. It’s a reminder that we humans are now the canaries and we seem hellbent as a species toward our own self-destruction, going out of our way to poison our cages, our foodstocks and our futures. We must start our efforts by changing the climate of misanthropy; after all, a self-loathing human is a dangerous beast and threatens to take a lot of other species down with it.

Once we’ve come to terms with our horrible-for-nature impacts, once we’ve accepted our responsibilities for past sins of commission and omission, and once we’ve realized that this planet is not all about us, we can begin to take tentative first steps to repairing our relationship with nature. And, yes, we are in a committed relationship with nature but, contrary to our human beliefs, we are most definitely not the most important partner in that relationship. Hell, our partner did pretty well before meeting us and will most certainly do just fine once we’ve departed. And we will depart sooner rather than later on our current trajectory, or more correctly we will be thrown out by an exasperated partner tired of waiting for us to change our ways and be a significantly more loving and more respectful significant other.

We have prioritized us and only us, at the expense of all others. We have blashemphed our inheritance and sullied our home. We have put our needs first, especially recently as the science became clearer while hurdles were thrown in the path of progress-seekers. Rather than acting in a manner that CELEBRATED, DEFENDED and AIDED our Queen in our role as consorts to nature, too many of us have DEGRADED, DESTROYED and EXPLOITED nature for our own benefit or for the benefit of societies that prioritize profits over people. The canaries have already given their lives for us and yet, still, we remain obtuse to the creeping gasses ready to suffocate our lives.

But as in all relationships, there is a chance to change our ways, although we might be on chance Nth by now. Our partner is very forgiving.

For far too long, humanity has demanded a subservience from nature. Some of our holiest books sanction our desecration in the name of the divine (and to the benefit of the few and the detriment of the most). We are the Lords, we are told, and we can bend Nature to meet our needs. But we are not Lords. We are simply a subspecies of simians that somehow managed to find a niche in time to proclaim our preeminence. We build edifices to and from our egos to ourselves and our perceived greatness. We’ll chop down giant, majestic trees to make the paper to make our words immortal, or until the next fire comes along. We use, we exploit, we degrade and we disrespect. Not all of us, and certainly not among the youngest of us, who seem to comprehend the severity of the bill of consequences that they’ll be paying for their ancestor’s transgressions against the environment. And I guess this message is specifically geared towards them.

It will not be easy to navigate your way forward in this new age of Mother Nature pushing back and standing up for herself. The ripples caused by the rising GhGs are well nigh ashore in our present world, manifesting as extreme everything. And these ripples will likely become tsunamis before the worst has passed.

What can we do? many may be asking. May I suggest an edit to How can we help? How can we become a consort to nature, a helpmate in the day to day and a warrior when called upon to fight on our partner’s behalf? We could do worse than look to the examples set by Phillip of Greece, George of Glasgow and Graeme of London.

In the introduction to his seminal book, The Bedside Book of Birds – An Avian Miscellany, Graeme Gibson wrote:

“With the zeal of a convert and the instigated imagination of an ex-novelist, I started taking note of, then collecting, and finally obsessively searching out texts that illustrated something — almost anything — about our human response to birds. This book is the result. It isn’t so much about birds themselves as it is about the richly varied relationships we have established with them during the hundreds of thousands of years that we and they have shared life on earth.”

How will we become the types of humans who deserve to share in a future with such a luminary partner? May I suggest a nature consort’s vow:

CELEBRATE NATURE. DEFEND NATURE. AID NATURE.

Until death do us part.

LEARN MORE AND DO MORE

How do we become better partners and better consorts for nature? Well, there are many steps that you can take and many great organizations doing work in your backyard that can help you gain a deeper understanding and appreciation for the role of nature in your life. Nature Canada, for example, works to help Canadians understand how to be better consorts to nature:

We believe that when the heart is engaged, the mind and body will follow. That is why, since our founding in 1939, Nature Canada has been connecting Canadians to nature, trying to instill in them a nature ethic – a respect for nature, an appreciation for its wonders, and the will to act in nature’s defense.

They’ve got many great programs, and one that would have definitely interested my Dad (and was a topic near to the hearts of Prince Phillip and Graeme Gibson) is birds in urban environments, the dangers that our cities present to our avian friends, and the steps being taken (or should be taken) to minimize the human impact on birds, and nature in general. Nature Canada’s Bird Friendly Cities program seeks to address the devastating impacts of our built structures on the avian ecosystem, and was launched because in “the last 50 years, North American bird populations have dropped by more than 25%.”

Thank you for reading our FOR THE LOVE OF NATURE series, be sure to check out the other articles as well!

And don’t forget to register for Nature Canada’s Pimlott Award Celebration happening this Wednesday on March 2, 2022, where Margaret Atwood and the late Graeme Gibson will be honoured and recognized as champions for birds and nature. Check it out here!