In the movie adaptation of N. Richard Nash’s The Rainmaker, Burt Lancaster plays a flamboyant confidence man who promises to bring rain to drought- stricken Texas. How? By using sodium chloride to “barometricize the tropopause” and “magnetize occlusions in the sky.” Are today’s climate engineers the modern equivalent of steam-era rainmakers, mixing dubious science with questionable motives to sell a desperately needed quick fix? Or is their mission a timely and necessary exploration of what may soon be our only remaining option for keeping the planet habitable?

Historically, weather-making and snake oil shared the same murky scientific bottle and were met with matching public derision. But as we move into the new millennium, prospects for reducing carbon emissions are dim. Greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere continue to rise even as Arctic ice melts more quickly than our best models predicted. With each failed effort, once-ridiculed fringe ideas – like fertilizing the ocean to create carbon-eating algae blooms, or spraying aerosols into the stratosphere to reflect heat – gain new, mainstream attention.

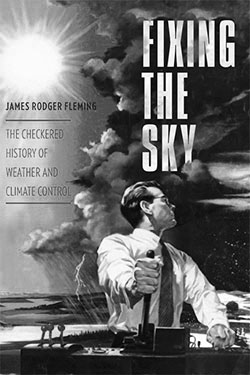

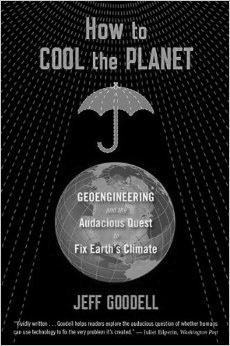

Both Fixing the Sky and How to Cool the Planet explore the controversial idea of geoengineering. While one author is doggedly skeptical and the other cautiously optimistic, both conclude that geoengineering may be a necessary but potentially perilous undertaking.

James Rodger Fleming’s Fixing the Sky is a historical account of our romantic and sometimes sinister infatuation with weather control. Fleming, a science historian, is unapologetically dubious of efforts to meddle with the weather. Using detailed examples of past follies, Fleming traces humanity’s weather-controlling ambitions from mythology to rainmaking scams of the 1800s and covert military efforts to use weather as a weapon.

We don’t have the knowledge or tools to accurately predict the effects of climate modification, he finds, so geoengineering should proceed only if it is accompanied by a more robust understanding of its scientific, ethical, social and legal implications. Stopping short of actually proposing how this might come about, he has assembled a potent set of parables that discourage hastily conceived climate-engineering exploits.

While Fleming’s book stands as a warning against geoengineering hubris, Jeff Goodell’s How to Cool the Planet is a thoughtful lay exploration of the subject. A journalist, Goodell’s perspective is balanced. He invites the reader on a three-year journey of inquiry as he surveys geoengineering options and interviews leading thinkers on the topic.

Goodell discards the more fanciful geoengineering schemes (mirrors in space aren’t going to work any time soon) and focuses on those that show promise, such as cloud brightening, ocean fertilization and the option he finds most workable: adding aerosols to the stratosphere. He illuminates the ethical issues these ideas raise through revealing discussions with the likes of Gaia-theorist James Lovelock, global-ecologist Ken Caldeira and Lowell Wood, a Pentagon nuclear-weapons guru turned climate engineer.

Geoengineering prompts no shortage of ethical questions, on top of the inherent technical challenges: Who decides if global geoengineering is appropriate? And if it is, who controls the global thermostat? Will geoengineering become a substitute for carbon reduction, allowing us to continue our over-consumptive lifestyles?

Goodell wrestles with two questions in particular: Should we be pursuing geoengineering, given how little we know about its effects? And can we afford not to? His conclusion is straightforward: The risks of catastrophic climate change are too great to ignore geoengineering. And if there are technical, ethical, legal and political bugs to work out, then we had better start addressing them now.

These books come as science and policy makers are shifting their views. We face the unfortunate reality that even aggressive carbon reductions can’t reverse damage already done to the Earth’s climate. Our climate will take centuries to recover. Fleming and Goodell point out that we have actually been inadvertently geoengineering the climate for over a century. The difference is that for the first time in history, we are on the cusp of developing technology that can change the climate purposefully. Proceed with caution, the authors warn.

Reviewer Information

Tom Bird has worked in the fields of social marketing, environment and health, energy conservation, and green energy development. He is currently working with a renewable energy development company.