Jane Goodall leaned back in an armchair by the window. It was a cold, wet southern Ontario afternoon in late April. Days earlier, Goodall gave an Earth Day lecture at the University of Toronto, and between travelling, interviews, convocations and distinguished luncheons, the planet’s most famous primatologist hasn’t had a chance to catch her breath. Her famous stuffed monkey, Mr.

Jane Goodall leaned back in an armchair by the window. It was a cold, wet southern Ontario afternoon in late April. Days earlier, Goodall gave an Earth Day lecture at the University of Toronto, and between travelling, interviews, convocations and distinguished luncheons, the planet’s most famous primatologist hasn’t had a chance to catch her breath. Her famous stuffed monkey, Mr. H, was peeking out from inside a reusable bag near her chair, eating his stuffed banana; her luggage sat neatly where she set it down moments earlier.

“What I do is travel 300 days a year around the world,” she tells me, “giving lectures, meeting people, giving interviews and getting exhausted.” You’ve given so much, I tell her, saying in a not-quite-fangirl way that she’s a living legend. Goodall interrupts my gushing with a joke. “I’m still living. Just,” she says. Everyone laughs; Goodall chuckles. We’re all thinking it, though she’s the only one brave enough to say it – Jane Goodall is getting old. The good doctor will soon celebrate her 86th birthday, and no one knows how many more she’ll have. And the frantic pace of her work and life is unsustainable in the long run. From a conservation perspective, the simple fact of her aging wouldn’t pose a problem – except Goodall may be the most famous living scientist in the world. She has unparalleled reach to advocate for people, animals and ecosystems. Her profile cannot help but overshadow the institution she founded that bears her name. And that is a problem.

We have to ask ourselves: What will environmental advocacy look like in a world without Jane Goodall?

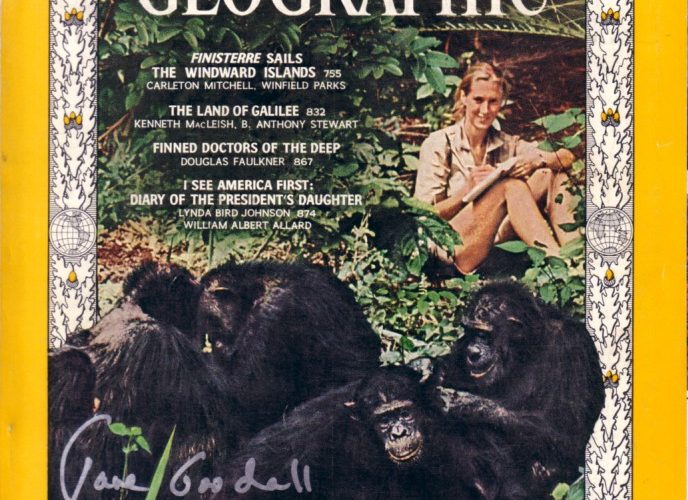

Our collective love for Goodall is as strong as the first time we beheld her blond ponytail and khaki shorts on the December 1965 cover of National Geographic. She’s sitting in the background surrounded by green foliage, pen poised over a field notebook, while a half-dozen black chimps groom themselves in the foreground. At 26, Goodall crossed the ocean to visit a friend living in Tanzania (Tanganyeka at the time) and secured a position as secretary for the legendary anthropologist Louis Leakey, whose fossil discoveries in East Africa helped cement the central importance of the African continent to human evolution. Leakey’s field work also included studying primates, and he agreed to include Goodall on his expeditions. Soon she was leading a solo project to watch chimpanzees in Gombe National Park in the country’s northwest corner. After four months spent trailing a pack of chimpanzees, Goodall observed her signature breakthrough.

“One of them began to lose his fear [of me],” she says. “That was David Greybeard. And he’s the one I saw using stems to fish for termites. Using them as tools, stripping leaves from leafy twigs to make tools. And that was a breakthrough.” While not unfathomable today, in the mid-1960s, this had never been seen before. Tool use was thought to be a strictly human practice. It was a triumphant moment.

While Goodall’s work and life are often romanticized, the truth is that her findings destroyed many long-held and ultimately untrue beliefs that animals didn’t possess emotions or personality and lacked the ability to wield rudimentary tools. Her discoveries to the contrary helped redefine our perception of humanity, detailed in her seminal paper, “Tool-Using and Aimed Throwing in a Community of Free-Living Chimpanzees,” published in a 1964 edition of Nature.

At the time, Goodall was not interested in the spotlight. Yet she knew enough to know that the images captured by Hugo van Lawick, the photographer and videographer sent by the National Geographic Society to record her work, would be useful. As an untrained woman, leading experts were skeptical of the veracity of her work. “They thought…that I was making this up. That I had trained the chimps,” Goodall says, “which would have been really something because they wouldn’t come anywhere near me.” Following the 1965 issue with Goodall emblazoned between the prestigious yellow bars of NatGeo’s cover, the resulting outpouring of media interest brought global attention to her projects – and, with it, funding. (The mythologizing of Goodall’s work also traces its roots to the publication of this iconic magazine cover.)

Despite the newfound attention, Goodall continued her work in the jungle as scientific director of the Gombe Stream Research Centre until 1986, the year she attended what became a fateful conference she helped organize in Chicago on understanding chimpanzees. It was here she came to realize that primates were under serious threat all across Africa. For the sake of the chimps, she embraced the role of advocate with the force of what was, undoubtedly, the Jane Goodall brand.

Her advocacy work began with wildlife awareness weeks in six different countries in Africa. Looking out an airplane window during her travels, Goodall caught sight of what was left of Gombe Stream National Park. Where once the jungle stretched thick and green across the horizon, all that remained was a small patch surrounded by barren hills. “It hit me,” Goodall says, that “if we don’t help the people, we can’t even try to save the chimps.” Since then, her advocacy morphed into the Jane Goodall Institute with branches around the world to promote conservation science, the protection and research of great apes, women’s health and reproductive rights and sustainable livelihoods. In addition, Goodall started Roots and Shoots, a youth-oriented conservation program that operates in 50 countries.

Andria Teather is a powerful woman. Her dark, shoulder-length hair brushes the deep orange-red of her shoulder-padded blazer as she sits across from me. Teather, CEO of the Jane Goodall Institute of Canada, is friendly and generous with her time. But she will suffer no fools – it’s not in her nature. Teather spent years climbing the corporate ladder at TD Canada Trust, where at one point in time she was the National Manager of the TD Friends of the Environment Foundation. Unlike many of her peers in the eNGO field, Teather is no bleeding heart, but a commander.

“I think not-for-profit needs many more people with a business mind, and a heart for the cause,” she tells me. “You’re not going to be successful in this role unless you believe in the cause. But I will tell you – I have never used my business skills more than I have in this job.”

The Canadian branch of the Jane Goodall Institute operates a multitude of programs to connect Canadians with global work on chimpanzees, maternal well-being and forest health across the African continent. They’ve expanded into areas like maternal health as a result of those first flights Goodall took over Gombe Stream National Park, where the deep connections between human well-being and the fate of the chimps became clear. Give women the chance to control their reproduction and fewer children may be born, she might have thought, which would then decrease pressure on forest for charcoal and hunting.

And here at home, the Institute recently launched an exchange program for Indigenous youth to travel to Uganda to experience the forest industry, learn forestry skills and bring relevant conservation knowledge back to communities across Canada. It’s about arming these youth with much-needed skills to pursue careers in forestry upon their return, equipped with a solid understanding of global development.

The organization, staffed with just 12 people, consistently punches above its weight, taking on multinational projects with a holistic approach to both human and conservation needs. “I’ve worked for five different not-for-profit organizations,” Teather says, and the Institute possesses the most compassionate but efficient team she’s ever worked with.

Yet even with a corporate mind like Teather’s at the helm, this small but mighty organization faces a significant challenge being heard over the near-constant adoration of their founder. “We’ve got a brand to die for [and] we’ve got Jane Goodall in our organization name. That’s really great,” Teather says. But even organizations familiar with the Institute as a separate entity from Goodall herself typically place the founder and her exploits on a pedestal. “Jane knows this,” Teather says. “We need to start making people understand that there is a Jane Goodall Institute in this country. And they need to understand that there is work being done. Really, really valuable work.”

Admittedly, it’s hard to see past the romantic image of a young woman handing a chimpanzee a banana in the jungle in 1962. And while Goodall has embraced this role and its associated branding for the sake of her mission to save the chimpanzees, it’s time for everyone – even me – to begin looking ahead with as much excitement and awe as we’ve looked to the past. Who, I wonder, will be the next young female scientist, inspired by Goodall’s verve and passion, to be immortalized between the yellow lines of National Geographic?

“I’ve never, ever felt like burning out. It would just be losing respect for oneself,” Goodall tells me in her hotel room, our time together winding down. “You’ve never felt burned out?” I ask. “I haven’t so far, and I’m 85, so probably won’t now,” she replies. “The time will come when my body says, ‘No, you can’t travel 300 days a year anymore.’ Then I will do more writing.”

One day, whether we like it or not, Goodall will no longer have the energy to rally the world to save itself. And on that day, the Jane Goodall training wheels will be removed from our personal environmental advocacy. It will soon no longer be enough to admire Goodall the scientist, the advocate, the person, so much as we must truly emulate her if we are to survive as a species.

Goodall doesn’t plan on slowing down anytime soon. She still takes a shot of whisky after every presentation to honour her mother. As you read this, Goodall is likely en route to another presentation, another distinguished luncheon, another interview to spread awareness and do her part for the planet. But when Jane is gone, how will we magnify and multiply the impact of her life’s work? Are we ready to let her words move from our hearts to our hands?

Leah Gerber has always been pretty nosy. Sometimes she still has trouble distinguishing between being curious and being rude. She loves exploring Canada’s nooks and crannies, especially on a bicycle. Her goal is to tell stories, visually and with words, that inspire change in our world, even just a little.