Breaking News

- 1 year ago

- WHERE THE WILDWAYS ARE

- 2 years ago

- They Call It Worm. They Call It Lame. That’s Not Its Name.

- 2 years ago

- Climate of Change Episode 4: ‘Rewiring the Future’ Review

- 2 years ago

- The Playbook for Progress Homepage

- 2 years ago

- Climate of Change Episode 3: “Faith, Hope, and Electricity” – A Review

Dollars and Sense

Building a Better Conservation Model

Written by Emma Bocking

Some weeks it feels like all I do is have meetings about meetings. A typical spring day as a conservation biologist in 2021 involves facilitating virtual breakout rooms, compiling grant reports and composing follow-up emails. Sometimes, especially at the end of winter when I’m nearing the longest stretch between field seasons, it’s easy to lose track of the big picture. Species at risk population numbers start to blend together. Wildlife habitats become (dwindling) polygons on my computer screen.

I often feel that I spend a lot of time talking about conservation and not enough time doing it. So, when I hear about another tool that could translate into more workshops, more meetings and more reports, I can be skeptical: another day, another acronym?

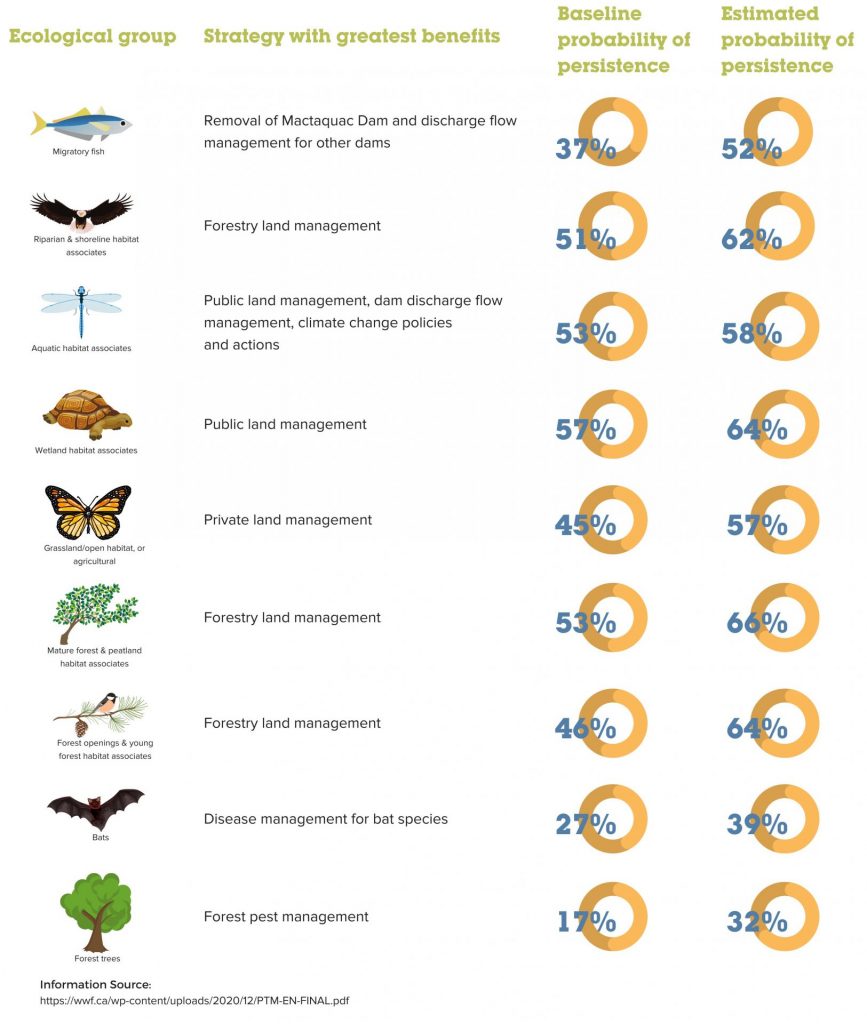

Thankfully, some tools deliver on their promise — such as Priority Threat Management (PTM), a decision-making tool developed by researchers at the University of British Columbia. The intent of PTM is to conserve the greatest number of species for the lowest cost. PTM draws on data and species experts to rapidly identify which conservation strategies will have the greatest impact on the largest number of species in a given region. Often, the focus is on species at risk, but the tool can be applied to ecological communities or species that are not at risk, as long as there is a way to measure the success of the actions against a management objective. PTM focuses on the costs, benefits and feasibility of management strategies. Most important, the goal is to move from planning to on-the-ground implementation as quickly as possible.

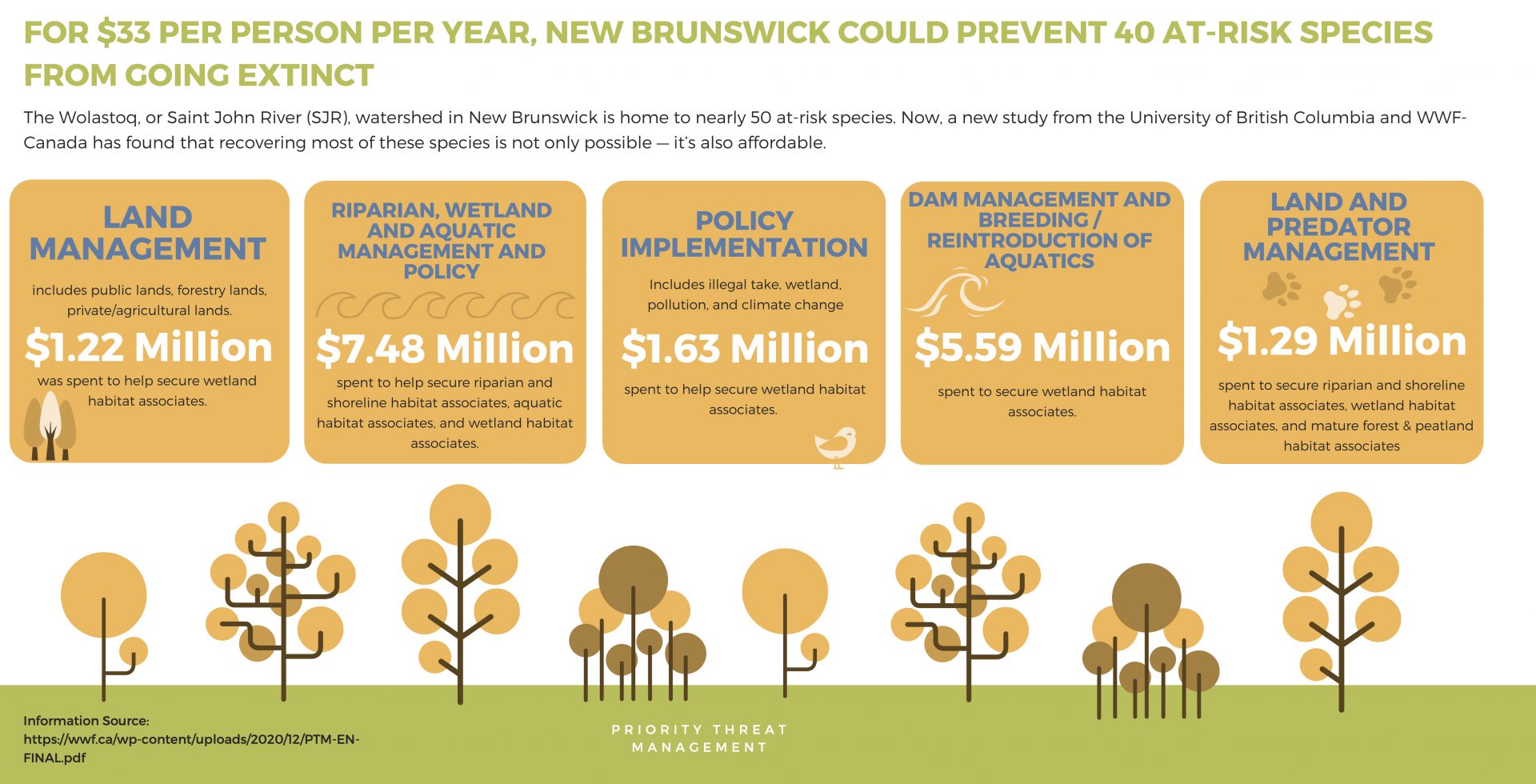

Recently, the UBC team collaborated with World Wildlife Fund Canada and partners to implement the first PTM assessment in Eastern Canada in the Saint John River valley in New Brunswick. After just one year, on-the-ground restoration was already underway in the watershed — a remarkably quick turnaround that suggests an efficient process and a tight-knit conservation collaborative.

The Saint John River is known as the Wolastoq (“Beautiful River”) in Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) — the language of the people who have lived lives that are culturally, spiritually and physically entwined with this landscape and the river since time immemorial. Simon J. Mitchell, VP of Resilient Habitats for WWF-Canada, has been working with the organization for nine years, but has lived and worked in the region for over 25 years and takes great pride in this place and its people. “We’re a water country, connected by the rivers,” he says. It’s an important area for biodiversity, but today much of it is at risk of extirpation. The PTM assessment included 45 species and one forest community group of conservation concern.

PTM was developed by Dr. Tara Martin, a professor in the Department of Forest and Conservation Sciences at UBC whose research focuses on how to use ecological data to make effective conservation decisions. Working with her is Dr. Abbey Camaclang, a postdoc in Martin’s lab with a particular interest in how we make decisions to conserve species at risk. She played a key role in the Wolastoq assessment, incorporating information from local partners into the PTM model.

The core of the PTM assessment is a series of workshops during which information is gathered from local and regional experts. Participants collaborate to define the objective, identify species and ecosystems of conservation concern, identify key threats, conservation actions and strategies, estimate the costs and feasibilities of each action, and estimate the benefit of each strategy. (In the Wolastoq case study, efforts were made to gather expertise from practitioners, provincial and federal governments, NGOs, academics, local Indigenous people and industry.) After the workshops, researchers compile the data, look up additional cost estimate information, and develop strategies that aim to benefit the maximum number of species for the minimum cost.

The final report from WWF-Canada and the UBC team identified 23 strategies, each listing the functional groups of species that would benefit and the estimated cost per year to fully implement the strategy. Sixteen of the strategies were methods that were already practised in the province, such as fine-tuning the existing provincial wetland policy and implementing invasive species management. The remaining seven were combinations of the 16 individual actions, optimized for maximum cost-benefit. The project team recommended three options that ranged in cost from $1.2–25.8 million/year. The most expensive options hinge on the removal of the Mactaquac Dam, which experts say is the only way to protect migratory fish such as Atlantic salmon.

The assessment revealed three hard truths about the region: 1) Under a zero-investment scenario (business as usual), it was predicted that all of these species will be extirpated within 25 years; 2) Under maximum investment, experts predicted species to have a 60 per cent chance of maintaining populations at a functional level over the next 25 years; 3) Even with all of this work, two groups — forest trees and bats — will require additional funding to develop new, innovative strategies to ensure their protection.

When Camaclang told me that many of the experts consulted in the Wolastoq were pessimistic about species’ survival, I was not surprised. It is frustrating to be a biologist in a world where climate change exists. We are keenly aware of the impacts on species and ecosystems, but we are not the people making climate policy decisions. The work we do well — building wetlands, surveying birds, planting riparian areas — are good actions cumulatively for carbon storage and climate adaptation, but bigger, more sweeping policy changes are needed.

Our current mechanisms of protecting species at risk, argues Mitchell, are just not working in the time frames that we need. The data tells the same story: nationally, monitored populations of vertebrates listed under the Species at Risk Act declined at an average rate of 28 per cent from 2002 to 2014 — and those are the populations that we are investing in through monitoring. Conservation work is constrained by human and financial resources, and climate change is accelerating the rate of species loss, so quick and efficient action is needed. PTM addresses these challenges by emphasizing cost-effectiveness and speed of implementation. By strategically focusing our efforts on proven strategies, we can start actions today and immediately begin budgeting for the rest.

Efficiency is a key component of PTM, but collaboration and a strong conservation network in the Wolastoq drove the actions on the ground. Groups like ACAP Saint John, the Kennebecasis Watershed Restoration Committee and the Nashwaak Watershed Association began implementing priority actions in the summer of 2020 to restore aquatic habitat by removing barriers to fish passage, revegetating shorelines and stabilizing banks. There is already a lot of expertise in the Wolastoq. Collaborating on priority actions helps to direct funding where it is needed most; in this case, to restoration practitioners that were ready to step in quickly to repair habitat for turtles, fish and aquatic birds at risk.

Both Mitchell and Camaclang look forward to seeing PTM being used in other areas across Canada. Although this is the first project of its kind in the Maritimes, there is ongoing work in British Columbia and the Prairies, and both WWF-Canada and UBC are keen to see more projects on the ground. Ultimately, says Mitchell, although protecting biodiversity is a shared responsibility, “rare species recovery stops and ends with the province and the federal government.” Projects that collaboratively address species at risk conservation, like the actions identified by PTM in the Wolastoq, need more government investment now if we want a shot at saving these species from extinction.

Actually doing on-the-ground work — planting the willow stakes, dredging out the dykes, engaging real people in the real world — is what keeps me going through these endless workshops, emails, delays and, ultimately, loss. I once heard that conservation is really, in the end, all about people — the people whose behaviour we influence and whose lives are touched by our work. We have lost a lot and the reality is, we have a lot left to lose — that’s why stories like these, where experts were able to act so quickly and efficiently to protect and restore habitat, give me hope.

Originally from Peterborough, Emma Bocking now calls the east coast home. She holds an MSc in Physical Geography from the University of Waterloo, and is a conservation biologist and aspiring naturalist in Halifax, Nova Scotia.