Megan Leslie: Monte, you’ve been at WWF-Canada for over 40 years. Tell us a bit about what the organization was like back then.

Monte Hummel: I joined WWF-Canada in 1978, when there were only three people in the organization. I came from Pollution Probe and I’d been an environmental activist for some time, so coming to WWF, with its scientific advisors and its corporate board, was new for both me and for them.

There are a few reasons I made the switch to WWF. The first one is obvious: I love nature. But I was also excited to come to work at a place that had a global network and dedicated funds to support conservation projects.

ML: Three people is not a lot of people. What kind of work did you focus on with such limited numbers?

MH: We funded projects in the field based on how much funding we had at the time. We’d get a slew of applications, and we’d have to choose which research to support. It was very reactive — we would get a proposal, I would circulate it to the scientific advisory committee, we’d make priority lists and decide if the project fit our criteria. This was how my first three years at WWF-Canada went.

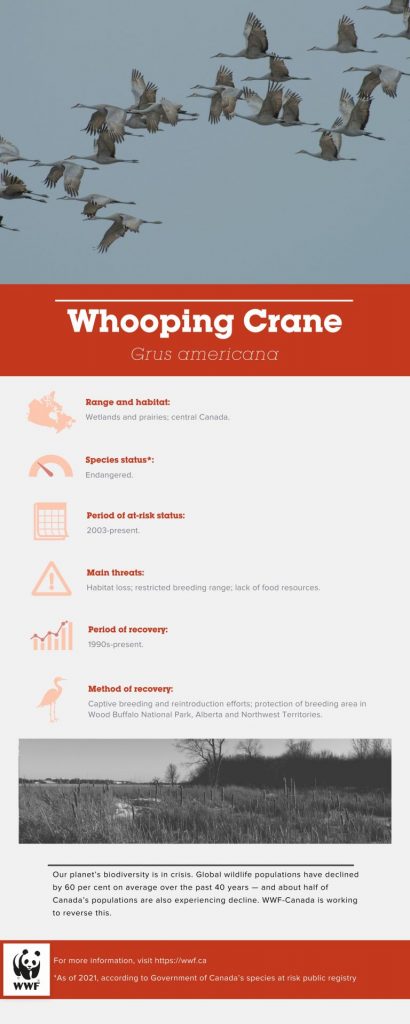

We focused our projects on species at risk and we funded really good fieldwork, so we got this reputation for doing good work across the country. That’s when we started dreaming big and thinking more strategically about what meaningful conservation for Canada really looked like. In 1981, I came up with a three-year regional project called Whales Beneath the Ice, then moved to a project called Wild West, which, as you can probably guess, was focused on grassland species.

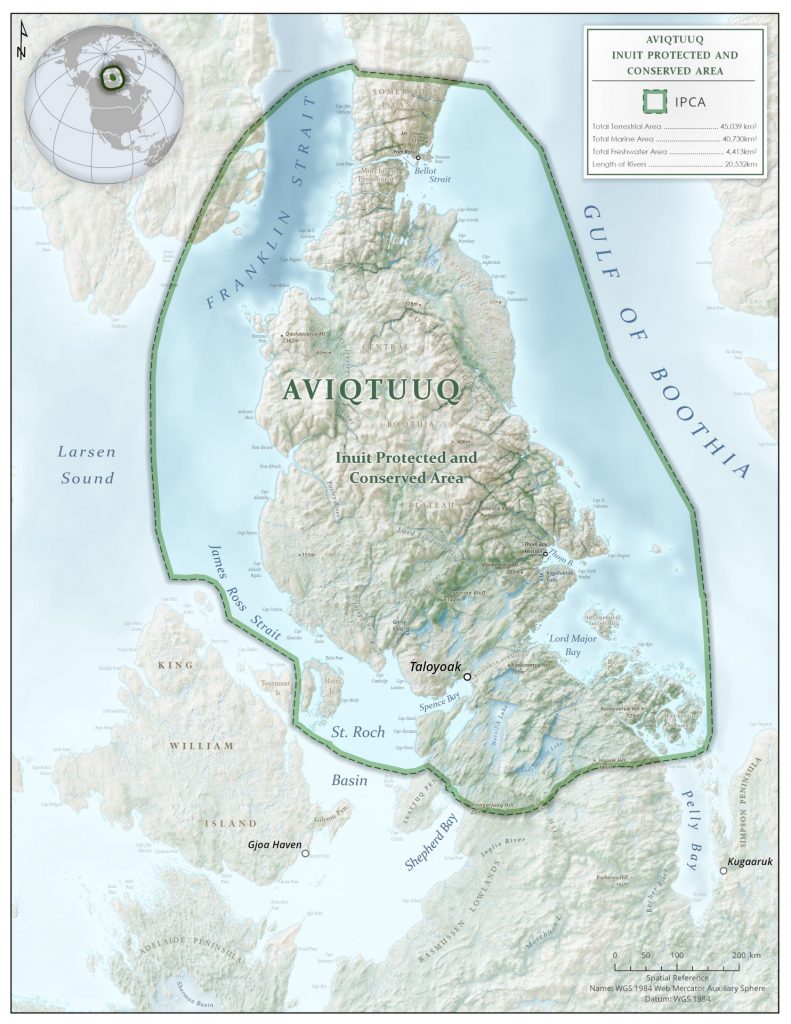

This was the start of a regional approach to conservation for us. We would create these regional committees to oversee the projects and decide how to spend the funds in order to achieve the conservation goals. And we became more proactive in this way. We also were able to work collaboratively with Indigenous communities this way.

ML: Can you tell us a little more about why this approach was important?

MH: I was raised in the north, and for me, it’s instinctive to work with Indigenous Peoples. We hired them to guide us and advise us on our projects, and ensured they were on steering committees with spending power, and added Indigenous leaders to our board. I was lucky to know personally how valuable it was for us to work together.

Now, this approach is even more formally ingrained in what we do. Indigenous community members really are showstoppers in the conservation field and it’s imperative that we include them in conservation planning and implementation — our work is better for it.