What happens when you give a third grader a power drill? With some wood and a little supervision, she’ll make her own keepsake box. Or, put her in that same space with a soldering iron, copper tape, LEDs and a circuit board, and she’ll learn first-hand how to direct the power of electricity. The Underground Studio at THEMUSEUM in Kitchener brings kids, parents and teachers together regularly to tinker, build, design and create.

What happens when you give a third grader a power drill? With some wood and a little supervision, she’ll make her own keepsake box. Or, put her in that same space with a soldering iron, copper tape, LEDs and a circuit board, and she’ll learn first-hand how to direct the power of electricity. The Underground Studio at THEMUSEUM in Kitchener brings kids, parents and teachers together regularly to tinker, build, design and create. We visited them on a day they were making gumball machines. All around us we saw kids of varying ages comfortably using all kinds of items from power tools to markers. And the best part? They were participating in the maker revolution.

All over the world, a new maker culture is reinventing what older readers may have experienced as Do It Yourself. It’s a burgeoning network of “makerspaces” – physical spaces operated by community members where tool libraries, training and collaboration combine to bring the process of production back to local hands. This year, Hackerspaces.org reported 1336 of these makerspaces active worldwide, with 355 opening soon. It’s a growing movement, and it’s only getting bigger.

This resurgence of making comes at the same time as the increasing popularity of online marketplaces, the online sharing economy, innovations in creation like 3D printers and a mass movement towards knowledge freedom and sharing with projects like Wikipedia, open source and Massive Open Online Courses. In 2015, members of Etsy, the online marketplace for handmade products, sold $3.21 billion in merchandise, while sharing services such as Uber (car sharing) and Airbnb (home sharing) are worth over $66 billion and $30 billion (both $US) respectively.

With over 135 million adult makers in the US alone, and over 2000 planned or active makerspaces worldwide, maker communities show a thriving new future of production. Makers are finding ways to bring local production together with new technology, a task that many in the past thought impossible.

Why make?

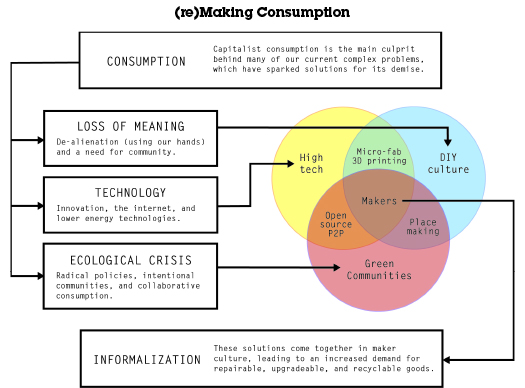

Every society that has experienced a capitalistic reorganization of labour has experienced positive and negative outcomes. In the West and in places like China and India, capitalism has brought about unprecedented material affluence and rising standards of living. This organization of society has also provided the framework for rationalized legal systems, more liberal social mores, greater democracy, and the consolidation of universally recognized human rights. But, modernization and capitalism have also involved recurring trade-offs, most evidently in relation to the global ecological crisis but also, a pervasive “crisis of meaning.”

Since the 18th century and the Industrial Revolution, capitalist modernization has transformed the entire world. Karl Marx famously wrote about one main negative aspect of this modernity, that is, alienation from work. Where once individuals produced an entire chair to be proud of, they now work on an assembly line contributing just one screw. He believed this alienation from work leaves individuals feeling empty.

Perhaps the darkest and most extreme symptom of this crisis can be found in the prevalent Chinese industrial suicide issue, exemplified in the 2012 suicide protests at the Foxconn factory in Wuhan, China. Experts like Pun Ngai of Hong Kong’s Polytechnic University assert that China’s worker suicides reflect a deeper problem about the declining emotional health of China’s migrant workers. These workers are isolated from their families and face a bleak, low-paid existence on production lines.

Scholars and romantics have persistently railed against the loss of meaning that accompanies the systematic adaptation of the industrial worldview. Over the last two centuries, they have often envisioned alternative approaches to the modern world. But their ideas were invariably rebuffed because their vision of a small and beautiful society of artisans seemed to require would-be revolutionaries to embrace a life of simplicity or, from the perspective of the average shopping mall citizen, gross poverty. Their utopia, it seemed, was incompatible with modern amenities like dentistry, antibiotics and new iPhones.

“Creating is not just a ‘nice’ activity; it transforms, connects and empowers.” It leads to increased feelings of satisfaction, self-esteem, creativity and joy.”

No one has been able to demonstrate a feasible alternative modernity that reconciles modern science and technology with artisanal craft production or the efficiency of the modern market with locally sourced manufacture. Sustainable development specialists working for decades have not found a way to slow down economic growth through small-scale lifestyle innovations.

However, more than ever before it is clear the planet cannot accommodate current levels of consumption, and change must happen. The most recent release of the Planetary Boundaries report (see page 43) argues that we have crossed four of Earth’s nine key boundaries, and are quickly encroaching on at least two more.

New technologies in small-scale fabrication (such as 3D printing) and communication have made it possible for us to dream once again of a small scale, locally oriented, low-impact form of society. Today’s dream of localism is scientific, innovative, technically progressive and able to sustain relatively high technology. It goes way further than gumball machines.

Exploring the solution

Maker culture provides a niche for ecological economists to explore the ways in which re-emerging social connectivity, new technologies and radical redefinitions of our economy come together. Here we offer five ideas to drive home the significance of maker culture as a model for the kind adaptations that are necessary in the face of coming global ecological and economic challenges:

Generate community-owned resources and production. Makers and maker communities typically prefer to use materials that are locally sourced or traded with other makers in the area. This strips away the complexity of the global supply chain, eliminating overhead costs such as transportation, packaging, mass advertising and storage. Diana Ivanova and colleagues, in their Journal of Industrial Ecology article (2015), argue that household consumption contributes up to 60 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, mostly from environmentally costly production.

Create ultra-affordable, recyclable, and replicable housing and goods. People will potentially be able to make or 3D-print pieces of any product using design ideas and templates on the Internet. While some jobs may suffer, new ones will open up to create and release the designs of these products.

The very idea of repairable home goods is revolutionary enough on its own, but an inexpensive, reusable and replicable house could change the face of poverty forever. Such ideas introduce an entirely new kind of economy. Rather than a growth economy, the

(re)Maker economy would help reorient individuals away from a culture of work and production, and instead focus on what they need to psychologically thrive.

Return to the local landscape and ignite new ways of learning. A local (re)Maker economy would rely on locally available materials and would start from the assumption that people would be more satisfied even with reduced income and consumption of goods. Urban salvaging and reusing of existing materials would be necessary for success, and when these run out, locally sourced materials would be used. Future makers would see a marked reduction in the accessibility of global materials, which might help to reflect the actual cost of our goods. Instead of paying five dollars for many cotton T-shirts, we may begin paying $40 for one that we take really good care of. Makers tend to be creative in their problem solving, using one material for many non-traditional purposes. With this, makers also experience a whole new way of learning that engages hand to brain learning processes. Thus, fewer goods will go a longer way.

An economy that contributes to personal mental health. A recent article in The Guardian entitled “Creating is not just a ‘nice’ activity; it transforms, connects and empowers,” argued that making leads to increased feelings of satisfaction, self-esteem, creativity and joy in those that participate in it. Our research echoes this argument. Thus, not only does the act of making challenge the dominant capitalist way of thinking, but it also inserts meaning into the process of consumption and production.

An economy that contributes to a community. Makers rely on the network of other makers, in their community and online, to learn to perfect their skills and to share resources. There is also a thriving gift and barter economy between makers. While conducting our research in Prince Edward Island, we found that almost every maker was willing and interested in bartering with other makers. During our interviews with Etsy shop owners across Canada, we found they were similarly open to trades and bartering. Some makers trade for the materials necessary to make their products while others trade their finished products (for example, beer and bread for pottery). Both kinds of trade were common.

Capitalist consumption has set up a unique situation for the resurgence of DIY While earlier DIY movements were seen as anti-progress, the new maker movement incorporates technology as a response to ecological crises. Makers thrive in the current social, ecological, and economic sphere by combining the values of environmentalism and opportunities of technology to remake the world.

A caveat

Making lowers the ecological cost of any material or consumer goods by stripping away wider distribution chains, packaging, etc. It could also provide a new framework for individuals to find meaning in work and production, displacing conspicuous consumption and alienated work as a means for happiness and fulfillment. What is changing is that the Internet-facilitated collaboration combined with small-scale production technologies is creating the possibility for a different kind of solution to local and global problems. The (re)Maker vision of networked, local production emphasizes the importance of living within local ecological means, and of local community and interdependence. However, there is a caveat. Any seismic shift towards a local, bioregional, DIY, maker economy would have serious unintended consequences.

Making is typically domestic and informal – and, as such, invisible to the fiscal system. Any significant decrease in the formal economy in this way could, potentially, divert revenue from the state, and undermine cherished features of modern societies that have so far been expanded because of capitalistic economic growth. This includes anything from health systems and investment in infrastructure, to childcare, schools and the military.

The eventual success of a maker economy would depend upon the extent to which such systems could be redesigned to benefit everyone. New possibilities create a basis for a new world, but they present even more significant challenges to the existing welfare and infrastructure commitments. Wicked dilemmas of low-growth economics is further explored in “Growing Pains” on page 35.

A society we can be proud of

After talking with nearly a hundred makers across Canada, we have found that maker culture has many parallels with the social commitments of the Guilds and Friendly Societies present in Early Modern European societies before capitalism. The main similarities are a commitment to community and local self-reliance, an emphasis on mutualism rather than reliance on the state, hostility towards corporate capitalism and large corporations, and local production as a backbone for a new economy of trade, sharing and longer lasting goods.

Modern makers also see their work as an implicit protest against rising inequality and environmental degradation. By teaching people how to repair and build they are helping those who are unable to afford to buy new products. By producing quality goods they are protesting against “throw-away” society.

Not only is this a strong anti-capitalist stance, but as Tim Ingold argues, the process of making is a mindful activity. Our research indicates that this mindful process enhances the self-esteem of kids and adults by producing a product that they are proud of.

Thus, an old vision of embedded production and community is re-emerging with new technology. Embedded production means that the production of goods is tied with the needs of a society.

At least potentially, open-source, microproduction and Internet communications could allow small-scale artisan production for local needs and consumption. In the future, people may not have to give up comfort to lower their impact. People may be able to work with local makers to repair a broken toaster instead of buying a new one. When they do buy new goods, they can buy them from local makers. In time, such an economy can stop consuming for consumption’s sake, and couple notions of a meaningful, good life with collaborative creativity.

Katie Kish is a mum, maker and teacher who loves to explore how people find meaning and purpose through creativity and curiosity. She is a PhD candidate at the University of Waterloo and Vice President Communications with the Canadian Society for Ecological Economics.

Stephen Quilley is an associate professor at the University of Waterloo’s School of Environment, Resources, and Sustainability, where he researches topics ranging from the long-term dynamics of human ecology and local economic development to neo-Pagan environmentalism and the role of traditional music in community resilience. You can read about his research interests and find calls for graduate students on his blog: navigatorsoftheanthropocene.com.

Stephen Quilley is an associate professor at the University of Waterloo’s School of Environment, Resources and Sustainability, where he researches topics ranging from the long-term dynamics of human ecology and local economic development to neo-Pagan environmentalism and the role of traditional music in community resilience.