This series, starting with this introductory survey by former A\J editorial intern and recent University of Waterloo Environment grad Semini Pathberiya, is focused on starting to answer the two metaphysical questions raised off the top in anticipation of determining just how big of a boat we’ll need to fit all the Canadians who work and take meaningful action in support of environmental matters, both close to home and that threaten our planet.

This series, starting with this introductory survey by former A\J editorial intern and recent University of Waterloo Environment grad Semini Pathberiya, is focused on starting to answer the two metaphysical questions raised off the top in anticipation of determining just how big of a boat we’ll need to fit all the Canadians who work and take meaningful action in support of environmental matters, both close to home and that threaten our planet. Pathberiya is our avatar and our guide for this first stage of our journey of self-discovery as she shares with us her insights, her excitements and her frustrations as an individual (and in her case, a newly minted environment grad). She is looking to make a difference – and make a living – by putting her passion for the environment to work.

JOURNEY OF DISCOVERY

When I was asked to make a survey of the Canadian Environmental Community, my first instinct was that this is going to be a laborious task. I sat down with a pen and a paper and tried to brainstorm what I consider to be the basic structure of this amorphous entity that has been coined as the Canadian Environmental Community. As a recent graduate, my impressions were mostly comprised of things of an academic nature, but I knew the Canadian Environmental Community is much more widespread, and is capable of touching all aspects of our lives.

Yet, I still had a hard time placing my finger on any one particular answer or trend. Some statistics paint a rosy picture of a community growing into the full flowering of its power. Other statistics suggest that we’re small, under-resourced and too easily dismissed. Truly, the Canadian Environmental Community is quite peculiar as it stands, and the recent federal election cycle hints at this dichotomy. The environment was the second most important topic in the 2015 elections (following Economy). But only 3.5 percent of the Canadians voted for the Green Party. With this in mind, two questions swirl in my head. Who makes up the Canadian Environmental Community, and why are we so disconnected?

There is a vast amount of work being done across Canada for the betterment of the environment, from individuals to grassroots organizations to government-funded programs. There are unsung heroes across Canada passionately committing their time and energy into the environmental sector, and there is a growing interest in working in the environmental industry. Canadians recognize the need and are willing to start the conversation, but there is no platform to recognize and connect these individuals and organizations.

This article explores three core pillars of our community that are crucial to a conversation about the environmental community: learning, working and funding. A wealth of knowledge in our community is pooled within our education system. Understanding our capacity to learn and create is key to understanding our potential to adapt and change. If the newly emerging student population is to succeed, we need a support network with people willing to share knowledge. To create opportunities we need funding – both education and job opportunities are inseparable from the resources required to fuel those endeavours.

Ultimately we need to create an online-based support network for the Canadian Environmental Community. Through much apprehended research, it became clear to me that in Canada, the environmental community is still defining itself. This is no surprise, but rather, a natural step in a movement that is less than 50 years old. The journey we are embarking on is a self-identifying process, with hiccups along the way. There is a whole lot of room for improvement and to stand strong as a community, we need to first identify our weak points.

This is a time of a generational and technological change; the greatest proof of this is the last federal election. Healing our Earth is a global dream, not just a Canadian dream. We have a massive part to play as an incredibly privileged resource-rich country. We need to be connected to our Canadian Environmental Community, whether it be your neighbour, grassroots group and/or local MP. Our collective voice needs to be louder than the few who are trying to silence us, especially by those who throw money at anti-environmental propaganda. Uniting ourselves is where we need your help – send us feedback about what projects you, your neighbourhood or community are currently working on. Help us find niches of environmental activities that are embedded in our society. Help others to connect and grow. Let’s build our Canadian Environmental Community as a family to recognize and support each other on this journey.

DEFINING OURSELVES

What is the Canadian Environmental Community? We’re still wrestling with the answer to this question and what it entails in terms of reducing barriers and building bridges. So we asked our friends:

“I think the Canadian environmental community would include everyone in the country, playing a variety of roles.” – Professor Stephen Bocking, Trent University

“I would include animal welfare groups, empathy to others and including non-humans, is the bridge to building care for ecosystems and species [in the Canadian Environmental Community]” – Dr. Annie Booth, UNBC

“[The Canadian Environmental Community] is a passionate, dedicated group of people, often with a very good sense of humour. It’s also a community that is trying to evolve to better represent the people of Canada and the connections between environmental issues here and our impact around the world.” – Sabrina Bowman, GreenPAC

SO YOU WANT TO START A NON-PROFIT

An issue is looming right in your face. You can’t ignore it. You must do something about it. You’re passionate about this issue, and you want to get more people involved to come up with creative solutions. So you want to start an eco-nonprofit.

Rob Shirkey started Our Horizon in 2013, a national not-for-profit campaign to have climate change warning labels on gas pumps (similar to warning labels on tobacco packages). Rob’s story is special. Inspired by his grandfather’s last words “Do what you love,” Rob abandoned his law practice and opened a small nonprofit. With his own money and a great idea to change how the world views fossil fuels, Rob started travelling from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, pitching his idea and gathering volunteers across Canada. On November 16, 2015, North Vancouver Council unanimously passed a by-law to place climate change warning stickers on gas pumps. It was a massive victory for a small organization.

Our Horizon is special because the organization is fully crowd-funded and is run on a shoestring budget. Currently Shirkey doesn’t get a monthly pay cheque for his work and he cannot afford a paid staff member. With such a unique experience under his belt, Shirkey’s knowledge certainly provides valuable insight to starting and maintaining an eco-nonprofit organization.

Semini Pathberiya: What motivated you to create Our Horizon?

Rob Shirkey: I recognized the need for a consumer-facing intervention to make people, communities and markets feel more connected to the impacts of fossil fuel use. Discourse on climate change tends to be focused upstream (e.g., tar sands, pipelines, etc.). But there is tremendous value in communicating hidden costs to end-users to actually drive change upstream.

Any memorable highs-and-lows along your journey?

The biggest high has to be finally seeing climate change disclosure labels for gas pumps passed into law in 2015. In terms of low points, apart from the frustrations that come with the struggle to do-more-with-little, the conversations with politicians wherein I realize that much of our leadership is too timid to put even a simple sticker on a pump. It’s quite sad, really.

What advice would you give someone pondering a similar start-up?

Honestly? Come from privilege. I would have never been able get my idea off the ground if it weren’t for the fact that I was fortunate enough to begin with some resources to make it happen. Unfortunately, philanthropy in Canada isn’t really structured to support projects that genuinely challenge the status quo. It’s sad to contemplate the number of game-changing ideas that will never see the light of day for a lack of financial support. Don’t get me started on foundations!

A CENSUS OF COMMUNITY

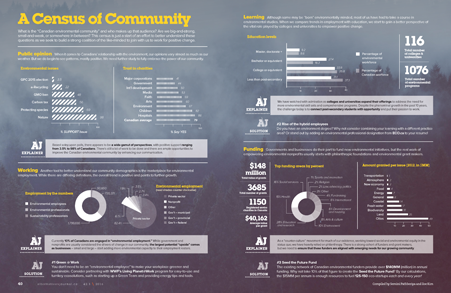

What is the “Canadian environmental community” and who makes up that audience? Click to see an enlarged versio of our in-depth infographic!

Sources for the graphic data in infographic: Trust in charities (Imagine Canada); Employment by numbers, Environmental employment and Education levels (Eco Canada); Top funding areas (Philanthropic Foundation of Canada); Amounts granted (Canadian Environmental Grantmakers’ Network); Environmental Issues (see ajmag.ca/senseofthecommunity)

ECO-WORKING

Congratulations, you’re hired! Now what? I quit my job after a year in a corporate environment. I realized I did not belong cooped up in a cubicle and I was not making the positive impact that I wanted to be making in this world. I was fortunate enough to be just starting out with my career, I do not have a family to support and I was able to make the drastic change. I want a job in the nonprofit sector, but the challenge is there is not enough funding directed to the nonprofit organizations that I wanted to work with. Waiting for an opening was not paying my bills. So where are the environmental jobs? And does working in the environmental sector really allow you to marry your passion for the cause with your affinity for the paycheque?

Coming out of university, I felt alone and disconnected. And yet, as I began this research, I was astonished to note that there are more than 1,800,000 people in Canada employed in the environmental sector – and an audience of more than 730,000 Canadians who are considered “environmental professionals” spending at least half of their time on environmental matters, issues and concerns. That is only counting the folks working within the fields identified by the Canada Revenue Agency as “environmental employers” which doesn’t demonstrate the richness of the nonprofit sector. Nor does it take into account the new start-ups, be they market-facing greentech companies or boot-strapped eco-groups.

As it turns out, the world of environmental employment is growing and growing – and I want to find my place in that exciting and expanding world. And, yes, you find a nice work-life balance in the environmental sector by doing what you love and loving what you do.

“Organizations like GreenPAC provide knowledge, statistics, technical expertise and shareable content. We also provide myriad ways people can get involved in the issues,” says Sabrina Bowman, outreach director at GreenPAC. “Canadian organizations are providing everything from helping to get environmental champions elected to government to providing organizing tools for communities to take on climate change, water protection and animal rights. Organizations are also acting as connection points to bring people from across the country who care about the environment together to work in an organized, coordinated way.”

Katherine Power, vice president corporate affairs for Sodexo Canada Ltd., a “quality of life services” company with deep roots in Canada’s resource sector provides sage advice. “Don’t think for a second that it’s ‘someone else’s problem’ or that you as an individual can’t possibly make a difference … you can if you work at it. Get involved, be aware of what’s going on in your area. Become familiar with, and look out for environmental activities locally. Encourage participation with friends and family.”

ECO-LEARNING

I consider myself to be incredibly fortunate to have a university degree (even with student debt to pay off). My undergraduate journey in a nutshell was this: My values and ideas were put into a mixer in nice colourful layers, blended and shaken in all sorts of directions and poured back out as a wonderful concoction — a person with a much broader understanding about the world, albeit a little confused about my next steps. My peers and I waded through the occasional quicksand of doom that comes with environmental studies, but we emerged as members of an environmental community that got dispersed all over the world. When looking at the up-and-coming postgraduates who are not far behind me, my heart leaps to see the increasing number of young and hungry in the field of environment.

There are more than 116 colleges and universities in Canada offering more than 1075 different and distinct courses many aspects of environmentalism and environment education. While some of these programs have been around for decades – including Trent University’s environment program under whose guidance Alternatives Journal was founded – there is a dizzying array of new programs that explore the next-generation of mobilizing environmental education to turn the sparks of inspiration into the tools of innovation for our community.

Dr. Annie Booth, associate professor of the Ecosystem Science and Management Program in the College of Science and Management, University of Northern British Columbia shares her insights. “We do research to create knowledge, hopefully that people can use, that can underpin both action and policy. We also teach the next generations to think, ask questions, find answers and to get involved in issues, including environmental ones.”

Our generation is growing up in a different era than our parents and grandparents. We are figuring out that the monotonous routine that worked in the past (get a degree, get a job, get a house and have a family) is not what quenches our thirst and that infinite growth using limited resources is not a viable option. The old routine is turning the planet into a boiling pot and we’re in it with nowhere else to go (at least for now). Thanks to global communication, our horizons are broader and we understand the need for change. This brings me hope.

Hope is part of the curriculum for most environmental educators. For academics, the broader role is “educating students about how to study and understand the environment and how human communities relate to their places in the world,” advises Stephen Bocking, Professor and Chair, Environmental and Resource Science/Studies Program Director at Trent University in Ontario. He also hopes that education serves as a “place of discussion and debate about environmental issues for the wider community,”

Of course, learning doesn’t end when the classes do. One of the most wonderful things about living in the 21st century is that we have access to a vast pool of resources. Learning is not limited to the younger generations and generally doesn’t require rigid sets of prerequisites to make the most of self-guided learning. Going to university and earning a degree is certainly one of my greatest achievements, but my learning is nowhere near the end. From MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) to professional development seminars and training – and with websites like Eco Canada – there is a world of educational resources available to you and no end to opportunities to learn more and do more in support of the environment.

ECO-FUNDING

AS I venture into this part of the article, I have more questions than answers. Funders and philanthropic foundations are vital contributors keeping nonprofits alive. We as a community are still more likely to be wearing hand-me-down Birkenstocks than new Pradas. We know that “money makes the world go around,” but does it really make the world a better place?

Let’s start by asking the most obvious question, why do we need funders? Currently, the vast majority of the 1150 registered Canadian environmental charities and nonprofit eco-organizations are not getting enough citizen support to survive without funders. All organizations, regardless of size, need a monetary base. Millions of dollars do get distributed via federal and provincial governments, but the environment is only one of many pressing government funding priorities. The processes involved are lengthy and can be overwhelming to new applicants.

Hang on a second, you say, isn’t there a group of funders providing “free money” to the eco-nonprofits? I hate to be the bearer of bad news but I must advise that there is no such thing as “free money.” Often enough, new and upcoming organizations find their pockets empty. Why? Because funding comes with strings attached. Funders are wish granters that sometimes – not always – tweak the outcome to fit their desires. You only get funding if you’re working in a particular sector on a very specific project. You have a better chance of getting funding if you are higher up on the nonprofit organization celebrity ladder. If your nonprofit is just starting off, it is not an easy task to sit down with funders and have that very difficult talk about money, especially at that very crucial moment of making or breaking it.

In a nutshell, the funding pillar of our environmental community is very much similar to the capitalism we experience every day. There’s a status quo – the money flows away from the 99 percent that need it most. But we can help change that with our words and advocacy.

We need to adjust the system to make it easier and less daunting. The funding system currently in place is not easily accessible. Organizations that have been around for decades have experience in grant writing and have enough staff who can dedicate the time. This is not so easy with a one or two person start-up. Unlike organizations that have already established roots in the community, newer organizations feel the pressures of adhering with the right funding partners. Is it better to take the money from a funder that has opposing views and compromise their principles? Or is it better to wait for the right fit and delay projects?

We stand today at an incredibly important time period. Everything around us is already changing – technology, ideology, the climate. The old Oliver Twists model of “Please Sir, can I have some more?” is not sustainable. We can already see the changes. Organizations like Avaaz and Change.org are taking activism to another level. Online crowdfunding platforms (Kickstarter, Patreon and Indigogo) are making donating as easy as clicking buttons. With the correct marketing, these websites can be incredibly successful. (Solar Roadways project collected over two million US dollars through crowd funding alone – much more money than any grant they might have received).

In such a precarious time, I conclude with these questions. How can we divert the “one percent money” to those of needs among the 99 percent? How can we reduce the need for funders and encourage citizen support? How can we use the capitalistic system to change itself? To address these questions, we need to unite. This is a key step in growing and expanding Canada’s Environmental Community to serve the needs of every citizen.

Semini is a graduate of the Environment and Resource Studies program at the University of Waterloo and a former A\J editorial intern.